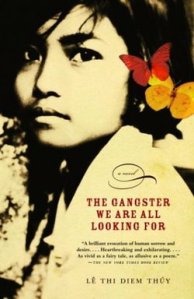

San Diego is reading lê thi diem thúy’s The Gangster We Are All Looking For, and Jade Hidle is there to tell us all about it.

On the evening of the Lunar New Year, lê thi diem thúy read from her novel The Gangster We Are All Looking For at Warwick’s bookstore in La Jolla, California, to celebrate its selection as this year’s communal text for the 2011 One Book, One San Diego program, sponsored by KPBS (http://www.kpbs.org/one-book/). KPBS station manager Diana Mackey, who introduced lê, stated that the novel is an important read for the city because so many young generations of San Diegans, like the novel’s adolescent protagonist, live between two cultures, and because lê’s book draws attention to the presence of the Vietnamese-American community and history in San Diego. lê herself expressed gratitude and excitement for being able to read at high schools and bookstores in the city where she came of age, to people for whom San Diego is home.

And, on a personal note, lê’s opening pronouncements of affection for the city resonated with me because I am a recent transplant to San Diego. It being the New Year, I was rather sad about spending the Têt holiday away from family, friends, and the Little Saigon streets familiar enough for me to know where the best bánh chung are sold. Since moving to San Diego, lovely as the weather is, it saddens me that I use my chopsticks more often than not to stir chocolate powder into my milk than eat phở, and I speak Vietnamese less frequently when I am not close enough to see my mother every day. So, in seeing lê here, hearing her recount her history and community here, and listening to her low, measured voice read her words in that inexplicably sad and lovely underwater quality they have in Gangster, I feel a little bit more at home—even more so when she tells me, “Chúc mừng năm mới” after signing my worn, read and re-read, and loved copy of her book. It is this sense of return, of healing, that speaks to the lasting power of lê’s novel and her admirable strength and source of inspiration as a Vietnamese-American female writer and artist.

This night, lê reads excerpts from the chapter entitled “Palm” because, she says, it was the hardest part of the book to write—she in fact started with only what is currently the very last line of the chapter, with little idea of where the story would go from there—and being in a bookstore full of finished, published books always compels her to recall, and value, the difficulties preceding the binding and shelving. It is this prefatory comment that sheds first insight into lê as a writer, and—while she is commendably, eloquently honest in her responses during the question and answer period—I choose to share here just a few of her comments that offer similar glimpses into the processes of writing and publishing Gangster, as well as her upcoming novel.

If you’ve ever wondered about the title of The Gangster We Are All Looking For and its unfulfilled promises of wild tales about shoot ‘em up gangbangers, I relay to you now what lê has to say about the misplaced expectations the title has created for some. While the father character was a literal gangster in Việt Nam, lê reminded the audience that it is important that the adolescent female protagonist speaks the phrase that gives the novel its title. Coming from her character, lê says “gangster” is a “projection of a bravado, an attitude of rebellion, the notion of a figure who can hold it all together. […] What will it take for you to be that person?” At this point, a woman sitting behind me in the audience gasps a “Wow” of revelation. I smile, pleased, wishing that I could be lê thi diem thúy when I grow up.

When asked about the intended meanings behind the net motif in the water-themed book, lê responds that as a writer she aims to create a net through language, which has a twofold effect. On the one hand, this net can connect the writer, readers, and characters, yet, lê points out, the concept and image of the net also admits her failures as a writer—her inability to raise everything up from the water. “Words can only do so much,” lê says, “but they’re all I have.” Here, I feel that lê’s reflection on the powers and flaws of memory, of writing, speaks in particular to stories from the Vietnamese diaspora, as so much has been rendered irrecoverable due to violence, flight, politics, trauma, pain.

Interestingly, in response to the slightly annoying token question of whether or not she has been back to Việt Nam, lê reveals that during her last trip she visited a publishing house in Hà Nội that is interested in translating Gangster into Vietnamese. She says that she is not sure whether or not the translation will actually happen, given that the civil war between Northern and Southern Việt Nam does not really exist in “official” Vietnamese history. Because of this, the foundational premise of her novel about Vietnamese refugees living in America reveals the glaring elisions in government-propagated narratives about the country’s history. For exactly this reason, I think that this translation would be important and interesting. For one, giving Vietnamese readers access to such a narrative would work to flesh out those holes that Việt Nam’s government has poked in the country’s history. Translation and distribution of Vietnamese-American texts into Vietnamese would likewise open up a trans-Pacific conversation between Viet communities, perhaps alleviating some of the pains of feeling that “home” has been lost and allowing the feeling that home can be many places, sometimes all at once. Right now, though, this is all speculation and hope, so I am curious to see if the translation happens and how Vietnamese in Việt Nam will respond.

To her readers’ delight, lê is currently working on her second novel. She says that whereas Gangster is “about silences” with “war off the page,” her upcoming book will “write into the silences,” writing directly about the war, including a Mỹ Lai Massacre survivor living in Linda Vista (in San Diego County). lê states that her second novel addresses “a history of American violence in relation to the war in Việt Nam.”

I would like to end with one of lê’s most beautifully conceived and articulated points (though there were many for us in the audience to revel in)—simple yet powerful, and inspiring to Vietnamese-American readers and writers alike. When asked why she chose to write the story of Gangster as her first novel, she says that it simply made sense:“When [my parents] carried me to this country, they carried me to English, so then I carried them through English, to you.” Gangster, lê tells us, is “an announcement that we are here.” Yes, we are.

Chúc mừng năm mới, everyone!

Jade Hidle is currently a doctoral student in the Department of Literature at UC San Diego. She aims to write her dissertation on Vietnamese-American literature, with a focus on how narrative structures map struggles of the body–miscegenation, disfigurement, skin color–and identity.

—

Did you like this post? Then please take the time to rate it (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. Thanks!

Julie: I’m glad you are enjoying the blog. If you keep reading ’em, I’ll keep writing ’em!

Thanks for this review and author commentary! I’m waiting and waiting to read this book and this only wets my appetite. Loving the blog, it’s covering much of the media I’ve been curious about.

I was JUST telling my friend that this book needs to be front and center on diaCRITICS. Anyone who was a kid in the US in the 70s needs to read this. Anyone who grew up with drunken parents should read this. Suffering exists and those gangster fathers suffer and bring their suffering onto their daughters. Smart move, San Diego.