diaCRITICS editor Viet Thanh Nguyen’s Top Ten Posts of the year 2011.

A little over a year and a half ago diaCRITICS began publishing. Since then, we’ve published two hundred and fortysomething essays, reviews, and interviews on literature, music, cinema, visual art, politics, and culture, of the American, Vietnamese, and Vietnamese diasporic kind. We also did a total overhaul of the site in Fall 2011, and it’s all been free to readers (but not for us or our sponsoring organization, the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network). So we began experimenting with ads from Google and amazon.com, which to date have earned us the grand total of–hang on–$5. I don’t expect you to click on ads for hot Asian women or whatever Google thinks is appropriate for this site, but please buy books and films from the links on our site. You’ll see a few of those links below. Buying here puts money in the pockets of the artists we feature and will pay for the peanuts I eat as I write my editorials. Let’s try it! Click on the links for any of these books by some of the authors mentioned below:

[amazon_enhanced asin=”1566892791″ /][amazon_enhanced asin=”B005HKSB4A” /][amazon_enhanced asin=”B005DIBYRM” /][amazon_enhanced asin=”0814758452″ /]

Our mission isn’t selling books, of course. It’s to talk about the vast diversity of cultural and political work that Vietnamese engage in or are featured in, in Viet Nam and all over the world, as well as the news of Vietnamese lives. For a group of people who are writing these things in their free time and for no compensation except for readership and a sense of community, we’ve done pretty well. We’re always looking for help in all kinds of ways–writing, editing, photography, maintenance of this site, brilliant business people who can handle our $5 or find us some more–so get in touch with us if you’re interested.

Now it’s time for us to take a look at all we’ve published in 2011 and highlight some outstanding writing. It was tough to pick out a top ten from all the posts, but here’s my pick in chronological order. Some of the posts are from our diaCRITICS and some from guest writers.

Let’s begin with Xaigon Mai’s Mondega’s “For the People” – A Montagnard Hip Hop Debut. I hadn’t heard of Mondega before this, so it was a thrill to hear (and see) some riveting rap from his YouTube videos. But Xaigon Mai (a pseudonym) also does a fine job of telling us more about Mondega, his life, and the fact that he (and she) are Montagnards. For those of you who don’t know, Montagnards are what the French called the dozens of minorities who lived in Viet Nam’s highlands, each of whom has a distinct culture and name. Xaigon Mai and Mondega prefer to re-appropriate the term the French used for their peoples. For diaCRITICS, it’s always important to point out how Viet Nam is a multicultural country in which race, ethnicity, prejudice and domination were and are important issues. Mondega’s lyrics make vivid how these issues stretch from Viet Nam to the United States.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DSxURjwbK7M&feature=related

Jade Hidle’s Meeting Strangers So Familiar: A diaCRITIC’s Dilemma recounts her personal experience in Portland, Oregon, stumbling across a bric-a-brac shop that had, among its many odds and ends, black-and-white photos from Viet Nam for $1 a piece. As any Vietnamese refugee can tell you, these photos exist in almost every refugee household–they were about all we could bring with us, if we were lucky, along with the clothes we were wearing. So it’s sad, as Jade conveys, to see these personal totems on display and on sale. Inevitably, we’d wonder who these people were in these pictures and what happened to them.

Dao Strom’s True Laws? (Thoughts on Selling “Vietnamese-ness”in America) has some relation to Jade’s piece. Dao Strom, author of a couple of books and a musician, has been thinking about what it means to create art as a Vietnamese person and about Vietnamese people. I think every Vietnamese American artist stops and thinks, should I deal with the war? Then he or she makes a decision to do so or not to do so. And any Vietnamese American artist who winds up dealing with her or his ethnicity–this thing called “Vietnamese-ness”–will also worry about whether their art is exploiting their ethnicity for profit. There’s no way around this intersection of race and profit in America’s art markets–or is there?

[amazon_enhanced asin=”1566892791″ /][amazon_enhanced asin=”B005HKSB4A” /][amazon_enhanced asin=”B005DIBYRM” /][amazon_enhanced asin=”0814758452″ /]

Lien Truong’s The Miniature Work of Diem Chau introduced us to an artist I’d never heard of before, Diem Chau. She carves Crayola crayons. How crazy and great is that? Before getting to the meta-artistic issue of using an artistic tool as one’s material, and not just as an instrument for art itself, we’re struck by the playfulness, the whimsy, the sheer intricate beauty of these tiny sculptures. For anyone who’s used these crayons as kids, or seen their kids using these crayons, there has to be some visceral reaction of joy. Unless you were one of those kids other kids abused by shoving crayons up your nose. Not that I would know anything about that.

Julie Nguyen’s Generation Trauma: A Different Kind of War Story was something I stumbled across online in Julie’s personal blog. I liked it a lot. Maybe because I have had war and trauma on the brain ever since I was a kid. My generation, which is roughly Julie’s, has a particular relation to trauma that’s different than our parents. Some of us might have been directly traumatized as a result of various things, but all of us have been indirectly traumatized by the war and what it did to our families. But whereas our parents were burned by the fire, we were only warmed by it. Julie’s post gets at what it means to be warmed by trauma–we’re not burned enough to not want to talk about it.

Anonymous, Bearing the Weight of History: A Young Cham Woman’s Story tells of the history and culture of Viet Nam’s Cham minority. At one time, before Viet Nam became the Viet Nam we now know, the Cham had their own kingdom and land. Then the Vietnamese began their long march south and conquered the Cham people and took their land. Does this sound familiar? It all goes to show that no nation has a unique claim on sanctity and heroism, as the Vietnamese would like to think. They’ve conquered and expropriated as much as anyone else. So now the Cham are a part of Viet Nam and the Vietnamese, and the article recounts one particular young woman’s efforts to remember her culture.

Linh Dinh, Mugged Then Shot: Linh Dinh on American Corruption. Here the poet/fiction writer/photographer Linh Dinh sends a flamethrower across the landscape of our American corruption–structural inequality, the entrenchment of the monied interests, our everything-but-in-name aristocratic system of closed doors, limited opportunities, and fixed games. He’s an angry man, and that can be a good thing. And although he’s Vietnamese, he doesn’t always write about Vietnamese things, whatever those are; plus it’s arguable that anything that affects a Vietnamese person should be of interest to a Vietnamese person. Writing about the corruption that touches all of us is one way out of the ethnic dilemmas mentioned by Dao Strom.

Trangđài Glassey-Trầnguyễn’s Paradise Shot: Norway in the World’s Arms was a piece I commissioned on the occasion of the 2011 Norway massacres committed by Anders Breivik. 69 people were killed. I was horrified by news of the event and remembered that Trangđài had spent time in Norway as a Fulbright scholar, studying the Vietnamese community. The beautiful essay merges the historical with the cultural and the autobiographical, bringing us news from a Vietnamese diasporic community I, at least, knew nothing about. The Vietnamese find themselves in dozens of countries all over the world, and in each of these communities we find unique stories like what Trangđài uncovers.

Kim-An Lieberman’s An Interview with Bao Phi was done to mark the publication of his new book of poetry, Sông I Sing, published by Coffee House Press. It’s a great interview, done by a talented poet talking to another talented poet, and it gets into all the compelling issues of art and politics that have been key to Bao Phi’s writing and performance. As anyone who’s seen Bao Phi do his thing on stage knows, he can put on a good show that’s both entertaining and provocative, full of wordplay and political consciousness. All those features are evident in this interview, too, which will hopefully send you running to your nearest bookstore to buy or order his book. But if you’re too lazy to do that, you can buy it here and give us a few cents.

Yes, we can’t get away from the market and capitalism even here. Trời ơi! That gets us to the last post, erin Khue Ninh’s An Ode to Ơi, the most popular post of the year. Who knew an ode to a two-letter word’s many meanings would mean so much to so many readers? And the essay itself isn’t very long either, its conciseness suiting its subject (but for those of you want more words from erin, she wrote an entire book…see below). erin mentioned the topic to me not long after I overheard a rough-looking Vietnamese man call himself Ba at the drugstore while he called his son on the phone, asking him in tender tones to make rice in time for dinner “con ơi.” I didn’t tear up but I felt that ethnic connection, that familial yearning, that communal identification that made me think of my own Ba. One word is all it takes, as erin shows.

[amazon_enhanced asin=”1566892791″ /][amazon_enhanced asin=”B005HKSB4A” /][amazon_enhanced asin=”B005DIBYRM” /][amazon_enhanced asin=”0814758452″ /]

So there you have it, the Top Ten of the year. Let us know what you think of them in the comments, or let us know if there are others deserving of recognition.

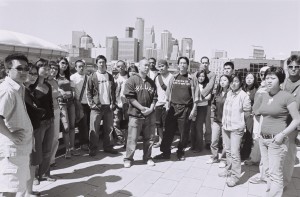

Viet Thanh Nguyen is a Los Angeles-based professor, teacher, critic and fiction writer, author of Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America and numerous short stories in Best New American Voices, TriQuarterly, Narrative and other magazines. He is the editor of diaCRITICS. More info here. Read his latest short story “Look at Me” here.