What do Henry Kissinger, the Hotel Majestic, and Jean-Théophane Vénard have in common? Danh Vo’s here to show us. Berlin-based conceptual artist Vo was born in 1975 in Vung Tau, Việt Nam. He fled by boat with his family in 1979, and they eventually immigrated to Denmark, where Vo grew up. His performance-based work, inspired by a biographical connection to historically-situated objects, might be considered cerebral or obtuse, by some. Yet diaCRITIC Nora Taylor, professor and art historian at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, goes on out a limb here and describes it as “very Vietnamese.”

After receiving this essay from Nora Taylor, we learned that Danh Vo has received this year’s Hugo Boss Prize, a $100,000 award given every two years for significant achievement in contemporary art.

Danh Vo’s We The People is on display at the Art Institute of Chicago, September 23, 2012 to November 11, 2012, in conjunction with Vo’s solo exhibition,Uterus, at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago through December 16, 2012.

In its earlier weeks, We The People also occurred simultaneous to a recent exhibit at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago called Ở / Works by Artists of Vietnamese Heritage.

[before we begin: like diaCRITICS? why not subscribe? see the options to the right, via feedburner, email, and networked blogs]

Ok, I’ll do it. I am going to out Danh Vo as a Vietnamese artist. I am going to break the taboo that has been hovering around him ever since he appeared on the world contemporary art stage in a big way a few years ago. The first exhibitions of his work in the US barely mentioned that he was Vietnamese and that was fine by the artist who is a Danish citizen and went to art school in Germany. By most definitions, and based on the kind of work that he makes, he would be a contemporary conceptual artist who happens to be Vietnamese. But, I would like to see him as a Vietnamese who happens to be a contemporary conceptual artist.

The irony of the omission of his biography in most of the critical writing about his work is that most of his work is extremely and intimately biographical. It is his method and presentation that tends to obscure those personal elements. Like Duchamp’s ready made, Danh presents objects that he acquires at auction, sometimes quite serendipitously, or not, and presents them as art objects. But, unlike Duchamp, the objects that he acquires have specific connotations to him yet, he offers them to the viewer to make his or her own associations, and connect to the objects on their own terms. The objects, therefore, appear generic, detached from context, dead, de-activated, like a relic or a residue of something past and unrecognizable.

So, what are these objects? In no particular order, here are some that I can think of without looking him up on the internet:

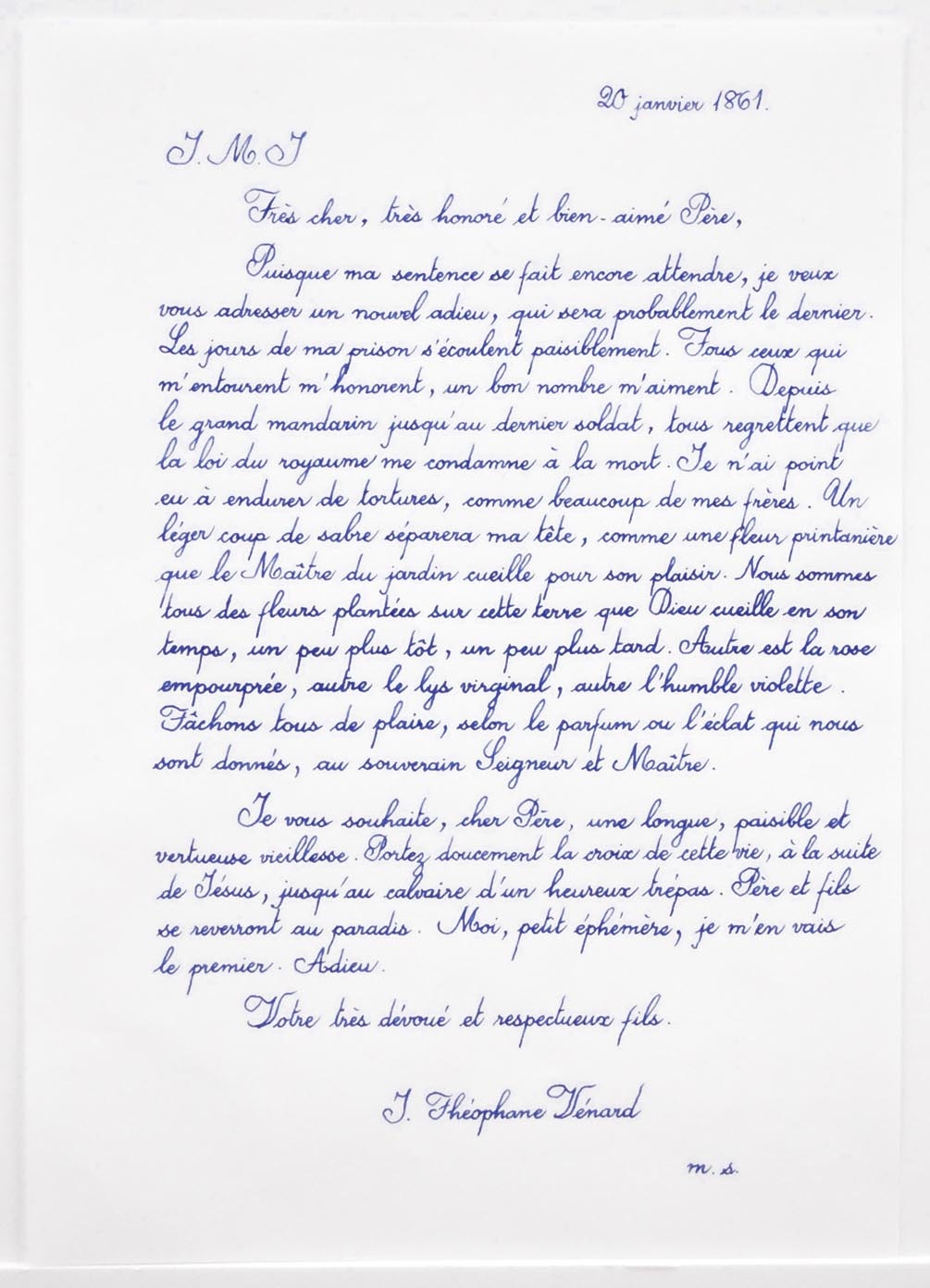

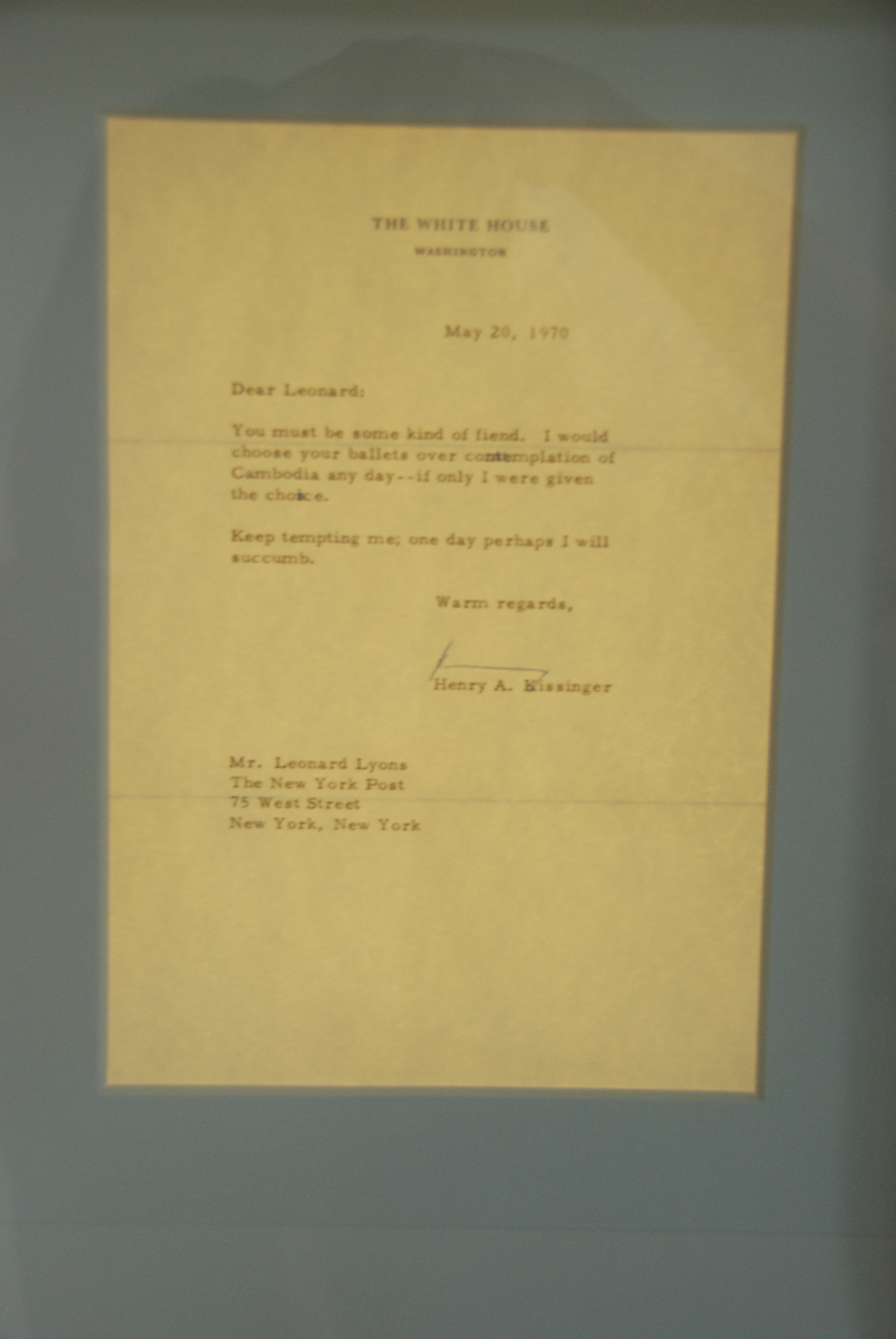

His grandmother’s refrigerator, pieces of the chandelier that hung above the table where the Paris peace treaty was signed in 1973 at the Hotel Majestic, his father’s wristwatch, a rice god from the Vietnamese highlands, a bear trap, thank you letters that Henry Kissinger wrote to a certain Leonard Lyons who had offered him theater tickets, a lock of blonde hair, and a blue print of the renovation of the interior of the Statue of Liberty in 1984. Those are the objects that he acquired and presented as is, untouched. Then there are those that are slightly altered such as: a letter to his father from a French missionary that he asked his father to rewrite word by word in ink and cursive lines; a medieval statue that was sawed in pieces to conform to airline security specifications for hand luggage, cardboard boxes of Carnation milk spray painted in gold, wallpaper made of the botanical encyclopedia drawn by a missionary in Indochina, and the Statue of Liberty in fragments, to scale, in copper, manufactured in China.

And what do they have to do with Vietnam?

Danh Vo, the Berlin based Danish artist, was born Võ Trung Kỳ Danh in Vung Tau in 1975. He and his family fled by boat in 1979. They were rescued by a Danish ship and sent to a refugee camp in Singapore. When they were allowed to seek asylum, his father requested to immigrate to Denmark because he believed the Danish ship was an auspicious sign. From then on, Danh’s life has been a series of providences. His name was changed to Trung Ky Danh Vo, first name Trung, same as his brother, who had the same middle name meaning middle. Danh grew up Catholic and therefore a minority both within Vietnam and in Denmark which is predominantly protestant Lutheran. But, living in Denmark would have also shielded him from the politics of identity prevalent in the diasporic communities of California and Paris. Vietnam was a concept that resided in his name, his family and the fragments that his parents and grandparents carried with them on their journey to Denmark. It was not an idea that could be represented by a photograph from Life magazine or a Hollywood movie. It was more intimate than that. I can imagine that when he went to art school in Germany, he probably felt closer affinity to Joseph Beuys’ installations of felt, fat and tin cans than to the photographs of Thich Quang Duc’s self immolation in the streets of Saigon. As a refugee, objects become signifiers for loss, material substitutes for an intangible memory of home or building blocks for a constructed future. They create stories, they fill the gap between the past and present as if time and place could be embodied in a ‘thing.’ As a pilot during WWII, Joseph Beuys was left to die in Crimea after his plane was shot down. He claims that he was brought back to life thanks to the fat in which the local Tatars covered his body. This claim has often been dismissed as pure myth by some biographers but I can’t help but see a correlation between Beuys’ social sculpture and displays of the objects that make up his biography (even if fictive) and Danh Vo’s family’s rescue at sea and the things that he exhibits.

Danh is not interested in metaphors. His objects do not stand for episodes of his life. Nor do they act like Beuys references to the materials that caused his artistic awakening. Nor are his objects ready-mades in the Duchampian sense of commodity. First of all, Danh is clear about the origins of the objects. They are not mundane found objects. They purchased by him at auctions. Like the surrealists who loved to scour the flea markets to see what they could happen on and turn those finds into art objects, Danh likes to find something for sale. But, unlike the surrealists, he is not necessarily interested in chance. He likes to know the history of the object in question. Those letters from Kissinger have a precise origin and trajectory. From the moment that Henry Kissinger dictated the letter to his secretary to when Danh Vo took possession of them, there is the unraveling of a story and that is the story that interests Danh. Each object could have A story or many stories. Danh is not fixated on any particular story connected to the object. Taking the letters by Kissinger as an example, there is the story of each letter, the person who wrote them, the person who received them and its content. I can’t help but think that Danh enjoyed a brief moment of revenge as he paid for them at the auction house. He didn’t just buy the material sheet of paper, he bought a letter that was written by someone and intended for someone else. Something that is very intimate. And the pleasure of acquiring it comes from the knowledge of the person who once held it. Like buying a book that was owned by a famous writer or an object from the estate of a celebrity, it is not the object’s aesthetic qualities or even historic qualities that count. Rather, it is the fact that we know the person who signed them. It is all the more powerful when that person happens to be the same person who ordered the bombing of your country.

Danh Vo’s work has made me rethink the very notion of Vietnamese art and I am grateful to him for that. I was beginning to wonder if Vietnamese art was becoming a cliché. Danh’s provocative obsessions with discarded history brings Vietnam’s past back to life somehow. But, he is not a fetichist, nor a romantic. He’s a hoarder who simply needs a few places to deposit his things for a little while before packing them up again. Those places happen to be the Art Institute of Chicago, The Renaissance Society, the New Museum, the MoMA, the Georges Pompidou Center, the Tate Modern, the Kunstmuseum in Basel…So, while most viewers of his work, including my students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, see his work as obtuse, cerebral, and overly conceptual, as they try very hard to make sense of his biography, I will go out on a limb and say it is very Vietnamese. And like the artist, I won’t tell you why.

__

Nora Taylor

Nora Taylor is a Chicago-based art historian of modern and contemporary Vietnamese art and professor of Southeast Asian Art History at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is author of Painters in Hanoi: An Ethnography of Vietnamese Art (Hawaii 2004 and NUS 2009) as well as numerous articles on Vietnamese art.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment! Have you seen Danh Vo’s work, and what did you think? Which other artists challenge us to (re)consider the relationship between history, identity, artifact, and translation?

here is lecture similar in content given by Taylor at the Renaissance Society: http://www.renaissancesociety.org/site/Exhibitions/Events/View.Danh-Vo-Uterus-Nora-TaylorAlsdorf-Professor-of-South-and-Southeast-Asian-Art-History-The-School-of-the-Art-Institute-of-Chicago-Is-Danh-Vo-a-Vietnamese-Artist.629.920.html?forceFlash=1