In 2021, it came to our attention that the featured writer, Linh Dinh, has expressed anti-Black, anit-Semitic, and overall harmful views since the publication of this post. Linh Dinh’s views do not reflect the values of diaCRITICS. This post will remain available for archival purposes.

An interview with Linh Dinh– a Vietnamese American poet and fiction writer, translator, photographer, and Pew Fellow- discusses the challenges of translating works in various languages, recurring themes of filth and grotesqueness throughout his works, and how politics is incorporated in art.

An interview with Linh Dinh– a Vietnamese American poet and fiction writer, translator, photographer, and Pew Fellow- discusses the challenges of translating works in various languages, recurring themes of filth and grotesqueness throughout his works, and how politics is incorporated in art.

Linh Dinh is a rebel artist. I first read his short stories in undergraduate school; I was studying sociology, but found my way into a creative writing class that sparked my interest in fiction writing.

Dinh’s stories were exhilarating. They were unlike anything I had seen as a student reading Raymond Carver, Amy Hempel, Ann Beattie. Dinh’s stories weren’t in the minimalist style touted by the academy. Instead, his stories exploded. There were men buying overseas brides, accidental eunuchs, Vietnamese prostitutes with attitudes. There was a grotesqueness to his work not seen in the quiet domestic epiphanies of other fiction writers.

Bad husbands, angry stepmothers, prison, and prostitutes are among the subjects of his debut novel, Love Like Hate (Seven Stories Press, 2010), in which a south Vietnamese café owner seeks a Viet Kieu husband for her daughter. Unbeknownst to the café owner, America is as much a sullen catastrophe as the socialized disaster of postmodern Vietnam made of mismatched billboards, local takes on foreign foods, and nightclubs playing heavy metal. The novel is both an intimate portrait of Vietnam and an insightful commentary on the country post-war that’s now populated with many who have little memory of the war.

[amazon_enhanced asin=”1583229094″ /][amazon_enhanced asin=”1583226427″ /][amazon_enhanced asin=”1930068190″ /][amazon_enhanced asin=”B008SMT7Y2″ /]

Dinh was kind enough to sit down for an interview over email about his novel, his broad range of work, and politics.

Your art encompasses many different mediums–at one point you did paintings, you’ve done poetry, fiction, photography, and not to mention your political essays and translation work. How did you get involved with so many different art forms? Which art form is your favorite to work in?

From childhood until I was about 32 years old I was convinced I was an artist. Writing began later, in high school, though I wasn’t entirely sure I was entitled to write in English. I came to the States at 11 years old, a rather awkward age to claim a second language, though this has also allowed me to hang on to Vietnamese. In college, while majoring in painting, I started to seriously think of myself as a poet. I also attempted my first translations at this time. I read Vietnamese folk poetry, then Ho Xuan Huong, then Doi Moi writers, particularly Nguyen Huy Thiep. My first book was an anthology of new Vietnamese fiction for which I translated half of the stories. To assemble this book, I had to take a trip to Vietnam, my first back in 1995, and this was only possible because I had won a Pew Fellowship for poetry and painting.

I gave up painting shortly after this for economic and strategic reasons. As I’ve said elsewhere, I didn’t want to risk failing at both writing and painting by having my attention so divided, although, subsequent years have proven that I’m perfectly happy and productive being chopped into two, three, or even more pieces. Right now I’m primarily writing political essays and taking photos, though, I still write an occasional poem, including one in Vietnamese about two months ago. Poet Nguyen Thi Thanh Binh kept emailing and calling me for a poem and I was rude enough to ignore her until one day I picked up my cell by mistake thinking it’s Press TV, the Iranian station, on which I’ve appeared many times. Finally cornered by Binh, I wrote a Viet poem I felt pretty good about, something I hadn’t done in years. When I lived in Vietnam from 1999 to 2001, my Vietnamese naturally improved, but I didn’t start to write in Vietnamese until I had gotten back to the States. Whether translating or composing, my work in Vietnamese has no doubt influenced my English writing, but how and to what degree, I’m not ready to pin down right at this moment. I have also spent nearly three years in Europe, so Italian and UK English have also had effects on me. About half of my book, Blood and Soap, was written while I was living in Italy for two years speaking and hearing nearly no English. I’ve translated some Italian poetry into English and Vietnamese, and if this wasn’t conceited enough, decided to translate some of my English poems into Italian. Crazy challenges are good for you, I believe, since they stretch your mind, but it’s also good to step outside of one’s language or languages, to refresh, tease, and question it. I’ve translated Eliot’s “The Waste Land” into Vietnamese, and published it. Most of these activities have not been remunerative, I should add, though I’ve lucked into a few grants along the way. At 49 years old, though, I live very precariously. As for what medium I enjoy most, it’s whatever I’m engaged at the moment. I’m a fairly compulsive person. I can’t help doing what I’m doing at each moment. Like most artists/writers, I could use a lot more time and money, but within my means, I try my best to stay productive. I block out most distractions. Thinking relatively well makes me happy.

What challenges have you faced as a translator? What is that process like for you—for example, how much liberty do you take with the text? Would you say it’s more of an act of creation or is it an act of going back to the intents of the creator? How does the process differ between translating someone else’s work and translating your own?

I try to be as faithful as possible to the original text, and I’ve gotten much better at this over the years. In the beginning, I was rather sloppy, I’m sorry to admit, but one learns as one goes along. I met poet Stephen Berg while still in my teens, and he would be very kind to me over the years, but from him I learnt how not to translate. Doing “versions” of other people’s poetry, Berg would take a lot of liberty, but that’s exactly what I don’t want to do, unless I’m translating one of my own poems, of course, in which case I’m not really translating but composing a parallel poem in another language. The task of the translator is to reveal to the best of his ability the author and not smearing himself into the work, thus distorting it. As someone who’s been translated by many other people, I know full well how annoying this can be. Before I wrote directly in Vietnamese, I was translated by seven or eight Vietnamese writers, and though they all meant well, and did what they thought was right, I wasn’t happy. Proofing translations of my work into Italian and Spanish, I’ve also made corrections in practically every line, every sentence. Of course, with a language one can’t decipher, one is completely at the mercy of the translator. A while back, I received an email from Sussu Laaksonen, “I read some Finnish translations of your work online, and as a writer and translator myself, I think it is my responsibility to tell you that I think these translations are of very poor quality and do not do justice to your work. They read like jokes. I think they should ideally be taken offline, and definitely not published in print if that is the intention.”

There are statistics that suggest that only three percent of books in the US are works of translation. This, of course, leaves many important writers off the radar of many American readers. What writers working in Vietnamese should we be paying attention to? Who’s doing important work? Whose work do you admire?

Many writers are off the radar, not just foreign ones. More distracted by pop media than ever and with so much junk on the internet people are reading less serious literature these days, and with the economy collapsing, most publishers are also in deep trouble. As for Vietnamese writers who should be available in English, I’m not as up to date as I used to be. I do have an anthology of new Vietnamese poetry coming out, however. Only a handful of the 27 poets included are known to English readers, and then just barely. Of these, only one, Phan Nhien Hao, has a full length collection in English, Night, Fish and Charlie Parker, which I translated. Nguyen Quoc Chanh is also well-represented in the anthology. He should be better known for sure. A few years ago, Chanh and I were invited to give a reading together in Berlin, and I’m happy to say that the Germans found out about Chanh through my English translation of his work. What we need are more translators from Vietnamese into English. Hai-Dang Phan is a good new translator. He wrote the intro to my anthology, by the way. As for fiction, Tran Vu has a collection in English, but most of his best stories haven’t been translated. It’s because they’re so difficult to translate well. Often, the easier works or writers get translated, while those who are more engaged with the language, who are richer, are bypassed. Tran Dan, one of the best Vietnamese poets of the 20th century, falls into this category. Personality also plays a factor, by the way. Bui Hoang Vi is a very interesting fiction writer, but he’s impossible to work with. He badmouths everyone and turns on all his friends, including me, so no one has translated him. I think he actually tried to translate a couple of his own stories with disastrous results. When I first discovered Vi while living in Saigon, I asked Nguyen Quoc Chanh, “These stories are great! How come no one has told me about this guy?” Chanh said, “Well, the guy is impossible. No one can stand him. He’ll talk to you one moment, but as soon as you turn your back, he’ll badmouth you.” Anyway, when it comes to translation, there are so many possible pitfalls, and few obvious incentives, yet I still think all writers should translate. It’s a great way to learn, very deeply, about language.

You touched briefly on the state of the publishing industry and conflicts within the writing world. Changing gears a little bit, have you experienced any difficulties getting your work published as a Vietnamese American writer? As a Vietnamese American writer whose work doesn’t necessarily fit into assimilationist and post-war reconciliation narratives? As an experimental writer?

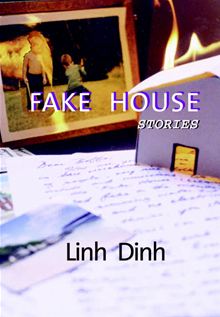

I haven’t worked very hard at getting published. Before my first book of any kind, I sent poems, stories and translations to literary journals, and got in a bunch, but not immediately, of course. Like everybody else, I was routinely rejected at first. In 1995, I met Dan Simon, publisher of Seven Stories Press, through Phong Bui, an old Philly friend who later became publisher of the Brooklyn Rail. We met in Brooklyn, as a matter of fact, in a bar, and I told Dan I was about to return to Vietnam for the first time. Dan then suggested that I do an anthology for him, and the result about a year later was Night, Again. My association with Simon has also resulted in Fake House, Blood and Soap and Love Like Hate, my three fiction books. As for poetry, I made my reputation in Philly through readings, mostly at the Bacchanal, a bar, but also because I managed to win a Pew Fellowship. From this local reputation, I was able to publish a chapbook through Philly’s Singing Horse Press, which was promptly praised by Ron Silliman, who had just moved to Philly. Later, Silliman hooked me up with Chax Press, now my primary poetry book publisher. Though I haven’t been passive, I haven’t been too aggressive in pushing myself or my work. My main focus, then as now, is to spend time doing the work itself. I don’t attend conventions. In fact, I hardly socialize with writers, in person or online. With my new passion of political writing, I simply sent articles to CounterPunch, Dissident Voice and Intrepid Report. Common Dreams used to publish me regularly, and I was very popular with their readers, judging from the comments, but it stopped featuring me, because I was too much for it, no doubt. One should never deform oneself to fit somewhere. Though I’ve been in the Guardian and New York Times a few times, I don’t really belong there, not because I suck, but because of what I say. Even with your best effort, it’s hard enough to say (nearly) all or (nearly) exactly what you have to say, what you must say, what you’re given to say, but if you’re not even trying to do that, if you’re too eager to pander, then you’re lost. You’re lost and worthless.

Do you see your political essays as a completely different genre of writing, or do you see it as an extension of your poetry and fiction? Can art and politics be separated? Should they be?

First of, art is always political. Enter any modern art museum, you’ll be greeted immediately with Minimalist oils, the same that decorate corporate lobbies, and unlike zigzags that gladden brutes, these CEO-sponsored smears and stripes cost legs, nuts, torsos and even entire countries. Huge yet hazy, they awe, but don’t irk clients. Or take Abstract Expressionism. Content-free, mostly, it appears apolitical, but it coincided exactly with the hyper masculine posturing of the American state, or consider Language Poetry. With its constant meandering and quick shifts, it echoes television, so that too is political, since it reinforces the tranquilizing and flattening media tactics of our masters. I can cite a thousand other examples where art or literature serves the ruling class, or reinforces its ideas. Also, what you choose to talk about reveals your politics. My political essays, then, should not be seen apart from my fiction or poetry because not only am I political, like everybody else, I’m always consciously political, and I always foreground my social and political thinking in all that I do. Further, the artist or writer is increasingly marginalized in this culture, with each expected to stay meek and docile in his little ghetto, where his self-worth is propped up by a handful of others just like him, although the larger society pays no attention to him whatsoever. Writers and artists should strive to be public intellectuals, I believe. Obviously not all, because everyone’s temperament is different, but when most intellectuals shun the public conversation your society is in deep trouble, which is exactly where we are now. I should add that I approach my political writing with all of my passion and skills for whatever they’re worth and my engagement with poetry and fiction have clearly tinted and informed my political compositions.

[amazon_enhanced asin=”1583229094″ /][amazon_enhanced asin=”1583226427″ /][amazon_enhanced asin=”1930068190″ /][amazon_enhanced asin=”B008SMT7Y2″ /]

Your political essays touch on various topics–the media, the election, the economy. What do you think is the biggest issue facing our society today? Or is it multiple, intertwined problems?

There are several main themes in my political writing. I keep emphasizing that the American government is not inept or clueless, but criminal that our rulers consistently facilitate war crimes abroad, and financial crimes and the erosion of liberties at home. These criminals that we keep electing do not serve us and have no interest in serving us. I have also been saying, for quite some time now, that the US is in irreversible decline, but that doesn’t mean we should be passive about this. Since 2005, I’ve taught a course called “State of the Union” at three different universities, Naropa, UPenn and the University of Montana. In this poetry workshop, students are asked to incorporate social and political issues into their writing. State of the Union is also the name of my photo and political essay blog. I started this in 2009, and have traveled to many states to observe and document, first hand, the economic and social unraveling of these United States. Of course, with my very limited resources, I can only do so much. If I had more money, I would be on the road all the time. My interest in societal collapse also shows up in my novel, Love Like Hate, but that book is also about rebirth, albeit a highly flawed one. In 2006, I spent 9 months in East Anglia, which gave me an opportunity to think more deeply about W.G. Sebald and his The Rings of Saturn, a meditation on personal and societal mortality. So decline is a major theme my work, but also violence, especially random or undeserved violence, and the gap or chasm between appearance and reality, hence my poems, stories or essays focusing on language.

I can see another theme in your work is filth and the grotesque. Your novel, for example, is filled with prostitutes, war, prison, etc. Yet it’s all told with a sense of endearing humor. You have said “I incorporate a filth or uncleanness to make the picture more healthy–not to defile anything.” Can you explain a little bit more on filth and healthiness in your work? Why is filth healthy?

We live in a consumer culture that, in order to sell, glamorizes everything, even extreme pain or squalor. Filth is photoshopped from the picture, or transformed and perverted into something irresistible, sexy and, ultimately, purchasable. The degradation that’s in my work, however, is not dressed up. By dragging degradation back into the picture, I’m making it more complete, and thus more healthy, and more sane. Sane comes from the Latin “sanus,” by the way, meaning healthy or sane. In contemporary Italian, “sano” simply means “healthy.” Anyway, by dragging dirt, death and squalor from behind the curtain, or under the table, into view, I’m merely showing what everyone of us is already aware of daily. In fact, several times daily. In any case, what I’m doing is hardly novel, but fairly generic when it comes to serious art or literature, because a work is not serious unless it addresses decay. That’s the covert or overt theme of each serious poem or story. If a work deals with time, it is already dancing with decay. As for prison in my writing, it is a metaphor for thwarted possibilities, which describes all of our lives without exception.

You said Love Like Hate is about a rebirth. That it takes place mostly in Vietnam–with only a few scenes in the US–has importance. If America is in decline, what do you think about Vietnamese society?

Love Like Hate covers the Vietnam War period, postwar economic collapse, then recovery triggered by Doi Moi, which means “Renewal.” During the war, a lot of money flowed into South Vietnam, so there was a kind of prosperity there, though the human suffering caused by all the violence from all sides was of course unspeakable. After the South collapsed, however, the country entered a new period of hardship, one result of which was the flood of Boat People fleeing the country. The vindictiveness, greed and incompetence of the Communist government played a key role, but it didn’t help that Vietnam was also attacked by China, a former ally of the North, to retaliate against Vietnam’s invasion of Cambodia, which of course also cost Vietnam a lot of money and manpower. The US, meanwhile, imposed a trade embargo, while the Soviet Union cut back aid because the Vietnam War was over and also because its own economy was in trouble thanks to its entanglement in Afghanistan. From this nadir, so to speak, Vietnam could only go up, and thanks to Doi Moi, it has, but many problems remain. Vietnam has always suffered from despotic rule, whether under a king, a Colonial power, a foreign-sponsored puppet or, now, the Communist Party. Though commentators tend to frame Vietnam’s most serious problems as merely political, many of them, such as corruption, nepotism and violence towards the weak, are obviously social, and hence cultural in nature. A great writer like Ho Bieu Chanh obviously knew this, and thus the central aim of his 64 novels is to reform the Vietnamese character. He wanted to show the flaws, and also the virtues, of course, of Vietnamese, and often to shame them into behaving better. Moving forward, Vietnam can certainly improve, but not just politically, but culturally and socially. One can even say that unless cultural and social changes are made, it won’t matter much which party, or parties, are in power. The challenges that face Vietnam, a small country living in the shadow of a behemoth, China, is different from what threaten the US, a superpower, but what’s going to hurt them all, and the entire world, is the end of growth as we’ve been used to and come to expect. Economic growth has been predicated on the available of cheap energy, namely oil, and since peak oil is here, we’re witnessing accelerating financial and political collapse in many countries. We will all become poorer, that’s for sure, but the real threat is the coming dogfight over the remaining oil, natural gas and other resources. Thanks to oil, the twentieth century was a time of unprecedented growth, but also of heretofore unimaginable horror. During this messy banquet, Vietnam got more gore than food, and now that it has partially made it to the table, the party’s nearly over.

With society in decline, what should a writer–or any artist–do? What advice would you give to writers working today?

A writer must have the big picture in mind. He must recognize the crises affecting his immediate community, his country and also the world. He will misread details if he doesn’t understand the larger dynamics behind them. The fact that he’s under-employed, ready to divorce, semi-homeless or addicted to pornography, for example, are not private, isolated events but parts of the larger picture. The relevance and resonance of his work depend on his vision, so if he’s narrow, smug or oblivious, it will show. Simply put, the writer must understand what’s happening. (No kidding!) Though he must have a comprehensive overview of what’s happening, he must also pay attention to the particulars, of course, as they are manifest in his immediate environment. He must be close to the ground, and by this, I mean he must investigate, literally, where he is, and who he’s surrounded with. He must continually observe people, first hand, and hear what they have to say, and he must experience his world physically, by moving through it with his own body, and not settle for filtered and degraded versions as beamed through a screen. It’s also time for a revival of Regionalism, which has had a negative connotation for too long now. Let’s welcome writers who are intensely San Mateo, Allentown or Lake Charles, the way Ho Bieu Chanh was intensely Go Cong.

Linh Dinh was born in Saigon, Vietnam in 1963, came to the U.S. in 1975, and has also lived in Italy and England. He is the author of two collections of stories, Fake House (Seven Stories Press 2000) and Blood and Soap (Seven Stories Press 2004), four books of poems, All Around What Empties Out (Tinfish 2003), American Tatts (Chax 2005), Borderless Bodies (Factory School 2006) and Jam Alerts (Chax 2007), and the novel, Love Like Hate (Seven Stories Press 2010). His work has been anthologized in several editions of Best American Poetry and Great American Prose Poems from Poe to the Present, among other places. Linh Dinh is also the editor of the anthologies Night, Again: Contemporary Fiction from Vietnam (Seven Stories Press 1996) and Three Vietnamese Poets (Tinfish 2001), and translator of Night, Fish and Charlie Parker, the poetry of Phan Nhien Hao (Tupelo 2006). He has also published widely in Vietnamese.

Eric Nguyen has a degree in sociology from the University of Maryland along with a certificate in LGBT Studies. He is currently an MFA candidate at McNeese State University and lives in Louisiana.

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment! What do you think are the biggest issues facing your society today? How do you express those issues and your opinions into your style of art? Have you ever translated or attempted to translate your work or someone else’s into a different language?

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Solid interview. Who asked the questions?

Best,

Dan

Eric Nguyen, MFA student and all-around great guy.

I interview the incomparable Linh Dinh http://t.co/LrYH5fAJk8 #vietnam #aapi #writing