From a reflection on being Vietnamese and spiritual, diaCRITIC Jade Hidle remembers her childhood relationship with Phật Bà, the Vietnamese Buddha, trying to catch her in the act of eating all of the offerings. These musings also bring up Hidle’s growing pains in America and her coming to an understanding of both her mother and their spirituality rooted in the figure of Phật Bà.

Have you subscribed to diaCRITICS yet? Subscribe and win prizes! Read more details.

I don’t consider myself a writer. Rather, I think I’m a reader. So, as a diacritic, it makes sense that I am, above all else, a fan of others’ work featured on our site. In reading (and loving!) Khanh Ho’s “Confessions of a Vietnamese Mormon,” I began to think about my own spirituality—its cultures, histories, pains, and humors. Before I knew it, I had spewed out pages upon pages of memories, layered Midwestern casserole thick. What follows is a small slice of that cheesy, tear-salted tater tot pie:

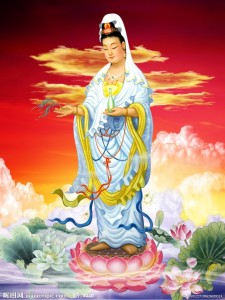

When I was still young in body, my mother showed me how to place fruit and tiny cups of water for Phật Bà. This is the Vietnamese name for the Buddha who is also known as Quan Yin (or Guanyin) in China and Kannon in Japan, where, I recently learned, she was the patron Buddha for immigrant sailors, largely in the 7th and 8th centuries as Buddhism spread in East Asia. (Her figure is often rendered similar to the Virgin Mary, as you can see below.) Unmoored from home and riding the tides, these sailors prayed to her in her representation of compassion, acceptance, protection.

Growing up in my mother’s attempts of creating a sense of home,Phật Bà’s altar sat on top of the record player where the Alvin and the Chipmunks Christmas album lay spin-less under the broken needle. “She watches over us and our home, so she must eat and drink before we do,” my mother told me. She guided my hand to pyramid the mandarin oranges, placing at the apex the one with a leaf curling from its stem.

“She eats and drinks…” I murmured. I looked at the Buddha’s porcelain face, concentrating on her Mona Lisa smile painted in a thin pink line—this hue of life. I tried to imagine it opening wide in a pink ‘O’ for a big bite of tiny hamburger, or being licked by a little porcelain tongue hungry for deposits of residual ketchup and mustard. “How does she eat?” I asked. “And when? At night? Will she save some for us?” My mother’s eyes smiled at me, which only made me anxious because she was not taking this seriously enough. “Does she get up and walk around too, Mom? Do you think she can climb onto my bed? Would she crawl into my mouth while I’m sleeping? Mom? How come you’re not answering me? Would she?”

“Thôi đi, con,” my mother said in exasperation, shooing me away. As she returned to the kitchen to unload the rest of the groceries, my mother called over her shoulder, “She do, how you say? In-vis-i-bi-li-ty.” (My mother has always enjoyed showcasing her skills with multisyllabic words in English.) Of course, I understood her beyond the sound of this word. I felt invisibility deeply. It was what I became when my mother was sad beyond comprehension, when her eyes did not seem to recognize my face. It was when my mother told me that she was going to stop taking pictures of me and stop celebrating my birthday when my baby teeth started falling out. And she did. It was, too, when everyone and everything that had happened in Việt Nam filled the space of our little apartment in San Pedro, California—unseen, yes, but undeniably present. These are things I at once knew and did not know.

I remained standing in front of the altar. My eight-year-old belly bulged in Phật Bà’s direction. She was still. I squeezed my eyes shut, imagining happy things—Disneyland, horses, Popsicles, hamburgers with spongy buns and wilted pickles, and then, helplessly, I pictured her porcelain arms emerging from the folds of her robe, the tink-tink of porcelain feet tapping down the hall toward my bedroom, Shaolin monk-kicking my teddy bear sentry into submission, her cold limbs goosebumping spots of my skin while it is warm with sleep, her closed yet all-seeing eyes peering into my dreaming face, her mockingly orange-scented breath on my cheek. (I think my dad had recently shown me the 1987 horror film Dolls, which was why my imagination cast her in such a mischievous light. Nevertheless, this was awe.)

My heart pounding, my eyelids heavy with fear, I forced my eyes open.

Phật Bà was still motionless. A moment of relief. But, no. Motionless could be patience. She was waiting. Plotting. My body bursted into a run. In my bedroom, I barricaded myself with stuffed animals and my recently released Mexican Barbie, Nina, whose smooth plastic body I hoped could ward off any threatening non-corporeal forces.

Over the next day or two, my courage was fleeting yet explosive. Periodically, I jumped into the living room with “Ah-has!” and an accusatory, elbow-locked point at Phật Bà. I never caught her in the act of eating, only my mother who, startled by one of my dramatic entries, flung her chopsticks into the air, scattering phở noodles and shreds of chicken from her soup bowl all over the coffee table where we sat cross-legged to eat every meal. “Trời đất ơi, cái con này,” my mother cursed me, and I saw her lips tighten in anger under big droplets of chicken broth that had splattered on her face. She picked up her chopsticks, shook them menacingly above her head, and chased me down the hall to my room where her anger, and my fear, subsided. A tickle fight ensued. I think I peed my pants during this skirmish, though, and my mother’s lips tightened again and remained that way until she shouldered my bed sheets from the laundromat back to our apartment.

From then on, I adopted more subtle tactics of surveillance. With several stuffed animals and Nina in tow, I slowly approached the altar with bated breath. This silent approach did not fool Phật Bà either. Each time, she was still and patient. Nevertheless, I noticed that the oranges softened and the water levels in her tiny cups gradually sunk. I did not understand her voodoo magic, but I kept her in the corner of my eye as my mother and I watched Melrose Place, reruns of Three’s Company, and Hitchcock movies. While she cursed Sydney, laughed at Jack and Mr. Furley or clicked her tongue and mumbled “ngu” at Chrissy, and practiced pronouncing the “er” sound in “birds,” I watched Phật Bà.

At school, a science-based assembly kept my classmates and I squirming as the salty smell of tater tots wafted into the auditorium from the adjacent cafeteria. Anthropomorphized versions of biology concepts emerged in costume, singing and dancing across a cardboard set. Sitting behind me, my childhood love Joshua Mathews punctuated each musical number with a “Ha!” or “Dumbass tree!”

During a particular boring musical interlude about a sapling, Josh whispered, “Hey, Jade.” I turned to him.

His eyes, always squinty under his unmanageable tuft of blonde hair, were squintier with smile crinkles, and he was fidgeting with the hems of his shorts as he always did when he was excited about something. He cleared his throat and announced, “Yo mama is so old, she’s as old as the crust on your underwear.” He immediately proceeded to nudge and jostle his friend Michael next to him, saying, “Oh, snap, that’s messed up, Mike,” as if silent, awkward Michael had come up with that “yo mama” joke.

The girls next to me looked at my crotch as if they would somehow see crusty underwear there on the outside of my jeans. They cringed and shifted away from me in their seats. I rolled my eyes and responded with a “Your mom” at Josh just to play along, but I turned back to the assembly with a smile on my face. This was how we pretended to deny what was real in our young hearts because we felt we had time enough.

Beyond that, my memory of the assembly is a blur—that is, until Ricki the Raindrop took the stage. A blue and furry man-sized raindrop, Ricki sang a song about how he rises and falls. In a duet with the sun, Ricki sang about the water cycle: “Solid. Sha na na. Liquid. Sha na na. Gasssss.” Over Josh’s heckling—“Dude, Mike, we can never become that guy when we grow up!”—all I could hear was one word echoing in my head: evaporation.

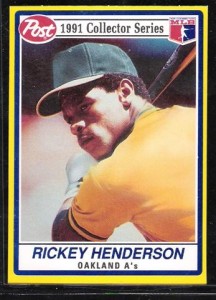

That afternoon in Latchkey, my disillusionment rendered me quiet and withdrawn. Josh and I did not have our usual conversations about our shared love of the beach or our understanding of being children of divorce. Careful as he was in his boyish love for me, Josh kept his distance, probably because he thought I was upset about the crusty underwear joke. Of course, I wasn’t. He was, after all, the boy I was going to marry, so my forgiveness with him was boundless. While I drew misshapen horses in the margins of my multiplication tables homework, Josh slid a Rickey Henderson baseball card across the desk to me. “Thank you,” I said, my heartbeat quickening with love for his generosity. “No big deal, it’s a duplicate,” he responded. When my mom picked me up at twilight, Josh and I mumbled good-byes, feeling yet uncertain.

When I got home, I dropped my backpack at the door and shuffled, eyes cast down, over to the record player. My mother mistook this defeated trudge of the newly science-minded for spiritual reverence and came up behind me, resting her hand on my protruding belly. “Lạy, Phật Bà, đi,” she said, urging me to pray. She pressed her body against my back to make me bow. I stiffened in refusal. I didn’t look at Phật Bà. “Talk to her like she is your best friend,” my mother said, taking my hands and pressing their palms together. She cupped my elbows and gently raised them up, then down, in the motion of prayer. “See? Not too bad.” She handed me an orange from the altar.

“How did Phật Bà drink all of this?” I asked, giving my parent a second chance, as children are still open-hearted enough to do.

“I tol’ you,” she replied, annoyed.

“Well,” I said, putting the orange back on the pyramid, “a fuzzy man-sized raindrop told me about evaporation today. That’s where the water goes, Mom. Not in Phật Bà. To the sky.” I crossed arms across my belly.

My mother, exasperated, clicked her tongue. She has never liked when I tell her about school. She feels I am talking down to her, spotlighting her shortcomings. (I learned to tell her nothing about my degrees in English. But, when I got to my PhD, I mentioned that my dissertation is about Vietnamese writers. She hesitated, then lifted her chin and told me, “I live that. I no have to read about it.” To cement me in my place, she added, “No man want marry PhD girl.”) She doesn’t realize that I revere her as one of the smartest, strongest people I know.

“Let me tell you,” she said, her lips tight, and my body tensed awaiting punishment. She switched to Vietnamese and her eyes travelled far away. I knew that the invisibility was taking over again. “When I was little, like you,” and she momentarily looked at, and saw, me, her daughter—flesh, blood, and memory, “I was playing at the lake in Đà Lạt. I never went all the way in because I don’t know how to swim, but I was splashing with my feet.” Here, she reenacted the movements of her girlhood body, and I longed to befriend my mother when we were both just little girls. I wondered if I would be able to recognize her. After all, it seems that most stories hinge upon the moment of recognition—the hero unmasks the villain; a parent encounters the future in the child’s quick, searching eyes; longtime friends confess the full depths of their formerly harnessed hearts to each other…

“Hot!” She switched back to English to emphasize the point to me, her foreign child. “It were so hot!” She continued, but in Vietnamese: “Many of the townspeople had gathered lakeside to cool off, and I could see people fishing and some boys on the banks were flying kites. But I was by myself.” She was, as in so many of her stories, alone. “I was watching the boys’ kite fly when my eyes travelled further upward, to the sky.” At this point, I was afraid that my girl-mother sees a plane and that this story will add to the staggering body count that her other tales have already tallied. My mother’s eyes gazed upward, where I only see the cottage cheese texture of our apartment ceiling. “And there was Phật Bà!”

“Wait—”

But my mother talked over my attempted interjection. “It was as if the ripples of heat were the folds of her robe,” she said. I looked to the altar beside us where the porcelain figure was cold to the touch. I turned back to my mother and listened: “Her face was so beautiful, filling the sky. Her eyelids were still heavy, but it was as if she was looking at me, as if she could see only me. And then she raised one of her arms and pointed. She pointed me to the hills.” My throat was dry, the anticipation unswallowable.

My mother continued, “Something told me to run. So I ran. I ran and left my sandals at the lake. I ran as fast as I could toward the hills green with fields of butter lettuce, until my chest was burning and my legs were like rubber. It was while I was running that the air raid sirens began to scream. So I ran with my hands over my ears. I made it to my grandmother’s house, where she smacked me for being outside while the sirens were sounding, but I knew she did it because she was relieved I was home. She often showed her love through anger. She pushed me away from the windows, and I lay on the hard-packed dirt floor of the kitchen to let my body cool. From the loudspeakers, a Northern Vietnamese accent told us that we were under twenty-four-hour curfew. So I stayed there for that night and for days after that. We heard gunfire in the distance. We ran out of rice, so my brothers and I ate bugs that crawled into the house.” I could envision my uncles doing this for sport, but when I pictured my mother catching bugs, it was a delicate process of waiting, cupping her hands, and tenderly plucking the legs and antennae from insects’ bodies. I imagined, because I know the tenderness of my mother’s heart, that she felt guilty for taking so much from these bugs, simply trying to live. “We survived,” my mother said. “That is how Phật Bà saved me. She brought me home.”

My mother’s eyes regained their focus and finally registered my face. When she looked at me, she said to me, in English, “Don’t cry. You ugly when you cry.”

I lost touch with Joshua Mathews after my mother abruptly decided to move the summer before sixth grade. I thought of him periodically, wondered about the man he had become. But, we never married as my young heart had hoped. Years later, in college, I found out that Josh died shortly after high school, of what I still do not know.

Phật Bà came to me in dreams for the first time in years, but not in the way that she has for my mother. I dream I am on the playground of my elementary school. It is twilight but children are outside playing, skipping through jump-ropes and kicking a soccer ball. The collar of a brown cotton sweatshirt brushes against my lips and suddenly I am aware of my body. I am inside this huge brown sweater with Josh. Though it covers the two of our child bodies fully, our limbs are tangled up together, as we pull each other closer and closer in this cotton cocoon. I turn and look at his face. He appears to me clearly. His eyes squint at me and his lips press into a thin pink smile. I lean my cheek against his and find warmth there.

As she did for the sailors riding currents Japanward so long ago; for the fear-stricken and lovely-hearted girl-mother of mine running toward life before I knew it; and for my yet-unborn children whom I hope will learn love very early in their long, long lives, Phật Bà connects us, protects us from that dizzying orbit of feeling lost.

—

Jade Hidle is a Vietnamese-Irish-Norwegian writer and educator. She holds an MFA in creative writing from CSU Long Beach and is working on a PhD in literature at UC San Diego. Her work has appeared in Spot Lit, Word River, and Beside the City of Angels.

_______________________________________________________________

Have you subscribed to diaCRITICS yet? Subscribe and win prizes! Read more details.

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. Join the conversation and leave a comment! What is your relationship with your Vietnamese spirituality? How do you and your family work through all of the different Vietnamese religious practices?

_______________________________________________________________

My dearest teacher– Jade, I always love your writing. Believe or not, i read three time and each time i still find some joyful, funny, silly of a little Jade girl. LOL…I also told my mom about you, especially this piece of writing. LOL… I was laughing with your round belly ..wink, wink..( wonder how big it was ???) and your lovely silly questions but very logical thinking! Honestly, this piece of your memory gave me a lot happy time while i was reading it, especially your mommy Buddhism. oh, I love your ” Little Jade face with innocent face and “Hiền dịu” ! Sorry i could not translate this Vietnamese worlds to English my lovely teacher, friend, and roll model ! Deep down in my heart, i really admire you and look up you as my roll model but hic,hic,hic,,,,I am not smart like you, Jade ! I am so jealous with your .IQ and your personalities: very calm , down to earth and quiet lady :)) .. Oh, Jade, it’s good thing that your face is not changed much compared to your little kid face that mean you are not aged right ? wink, wink…Jade, Suddenly i miss you so so so much, but don’t worry i love boy okie …wink, wink….ha,ha,ha…

Jade, write more and more something like this Jade…or something about Vietnamese currently situation In Vietnam if you don’t mind about involving a little bit in politic . It’s just my humor personal opinion because i though that you could become a Voice to help Vietnamese girls in Vietnam such as : 13, 14, 15 through 18 years old girl have been selling to south Korean, Chinese, Malaysia to become prostitute, slave wife, etc. They were abused and beaten atop of labor-intensive work forced upon them. A little three years old girl had to help her mom in brick kiln industry. She had to help his mom to carry each brick to put into the brick machine. Sadly and accidentally, her both two arms and two legs were stuck into the brick machine and were cut all of them. Furthermore, the educated lawyers, doctors have been imprisoned years in the prison because they have a gut to ask for a human right . Recently, a famous singer “” Viet Khang ” was imprisoned for four years. We don’t know if he is still alive just because he wrote two songs “Việt Nam tôi đâu”, và ” Anh là ai” to ask a human right for Vietnam people ! He is the First Youth generation who is so brave to complain about communist party in his two songs. He wrote about a Shamed scandal that Nguyễn Tấn Dũng — the Prime Minister of the communist party of Vietnam in 2008 signed and sold all of these islands to China such as, Ải Nam Quan, Núi Ðất, Thác Bản Giốc, Bãi Tục Lãm, Bắc Việt, and some islands in Hoàng Sa và Trường Sa. We still dont know where Viet Khang is kept in prison ??? Definitely he is beaten each day and starved….

Jade , if you are interested in those historical incidents and become a Voice for Vietnamese people who are still stuck in Vietnam, Please, help us… As refugee from a Communist country, two millions Vietnamese Americans refugees, one millions Vietnamese Americans immigrants and 90 millions Vietnamese who still live in our homeland deeply appreciate your voice and kind help !

Warm XOXO ,

Julie

Hi Julie, thank you so much for your kind (and charming) compliments on my post. While I don’t know if I can be an adequate voice for Viet Nam, I do thank you for raising several important issues and will look into learning more about these complex topics. Thank you for the feedback.

This is yet another delightful reflection post. It is a wonderful treat to read your writing. Your wording and phrasing are poignant, humorous, insightful, ironic, and poetic. You may not consider yourself a writer, but as a reader I certainly enjoy your writing and think your calling is to be a writer. You should publish your witty collection. In the meantime, I look forward to your next post.

Thank you for reading and for the kind words, Robert!

Oh my goodness, this is the absolute best thing I’ve read all year… possibly in all my life. I love this!

Thanks, Sal!