Eric Nguyen presents an in-depth review of the Vũ Ngọc Đãng’s film Lost in Paradise and the reason why it rises above the “gay film” genre: it has not only become a cultural phenomenon, but it also planted the seeds for substantial social change.

Have you subscribed to diaCRITICS yet? Subscribe and win prizes! Read more details.

Vietnam has a complex relationship with queerness. On the one hand, many in Vietnamese society view it as an import of Western culture. On the other, the country has been opening up towards the idea, especially with talks of reversing the ban of same-sex marriage.

Undoubtedly, the success of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender movement in Vietnam can be linked to the increasing visibility of LGBT people in the media. The same way movies like Brokeback Mountain changed the face of the queer other in American society, movies in Vietnam are sites of dramatic change in representation of LGBT Vietnamese people.

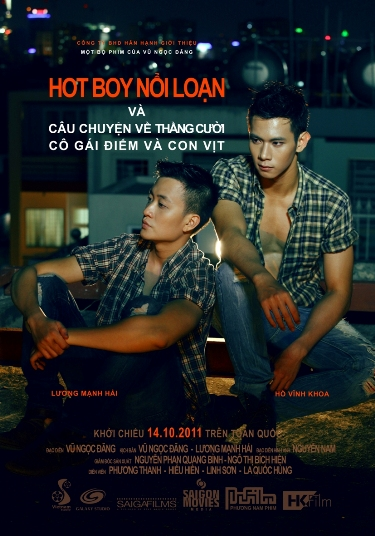

A major milestone in LGBT visibility came in 2011 with the release of Vũ Ngọc Đãng’s film Lost in Paradise (original title: Hot boy nổi loạn và câu chuyện về thằng Cười, cô gái điếm và con vịt). The film made headlines because of its gay characters, yet it wasn’t the first Vietnamese film to have queer content. 2009 also saw Bui Thac Chuyen’s Chơi vơi, which had lesbian subtext. Even Vũ’s 2004 directorial debut, Nhung co gái chân dài, had its bisexual characters. Yet the difference between those films and Lost in Paradise is the latter’s audacity to put queerness on center stage.

Lost in Paradise begins with Khôi (portrayed by pop singer Hồ Vĩnh Khoa) arriving in Saigon after his family disapproves of his sexuality. Vulnerable and lonely, he unguardedly befriends Lam (Lương Mạnh Hải) and Đông (Linh Sơn), “brothers” with a room to share. The tables quickly turn as Lam and Đông attack and rob Khôi, leaving him naked in their decoy home. We soon find out that Lam and Đông not brothers, but lovers as well as con artists and “hot boys” or male prostitutes. Khôi soon learns that survival in the paradise city of Saigon is tougher than he first thought. He wanders the streets, works as a porter, and gets injured on the job. Meanwhile, Đông betrays Lam, taking the stolen loot and leaving him in Saigon alone. Freed from an abusive relationship, Lam finds Khôi sleeping in the streets, wounded and penniless. After a brief fisticuffs, Lam brings Khôi home in an act of penance, pity, and loneliness. “I need a companion to wash away the blues,” he tells Khôi. “And by the look of things, so do you.” Soon after, they fall in love.

What is remarkable about the movie is not the gay characters, but rather the way Vũ treats them and avoids stock portrayals of such characters in a cinematic tradition that has historically marginalized them as gender deviants to be seen as comic reliefs. Instead, we see the couple engage in graphic acts of sex. We also see the gay couple living their daily lives in modern Saigon as they cook, go on dates, and even dress up their cats. In Khôi and Lam, there is a functioning gay couple. It is this normalizing of gay lives that is part of the triumph of the film.

Contrasted to the tenderness of domestic life are the brutality of the city and the differing attitudes of both characters. Hurt by past abusive relationships as well as his job as a hot boy, Lam sees gay relationships as inherently temporary, a sentiment shared by his former lover, Đông who breaks into the lovers’ apartment to reclaim Lam. “What is there to keep a gay love like yours permanent?” Đông asks in the climatic scene. “[It’s] fickle like a child with toys. [You] hook up, have a bit of fun, once you’re over it, find another toy.” With Lam and Đông, Vũ vocalizes the conservative societal view of gay love as immature and transgressive. This view is balanced by the liberal and more gay-positive view of Khôi who argues: “You can’t pick and choose your sexual persuasion, but you can certainly choose the way you live your life.” By giving his viewers such contrasts, Vũ asks his viewers to consider what life must be like for gays in Vietnam and what life can be like.

Such contrasts are the essence of Vũ’s film, making it more than simply a gay film.

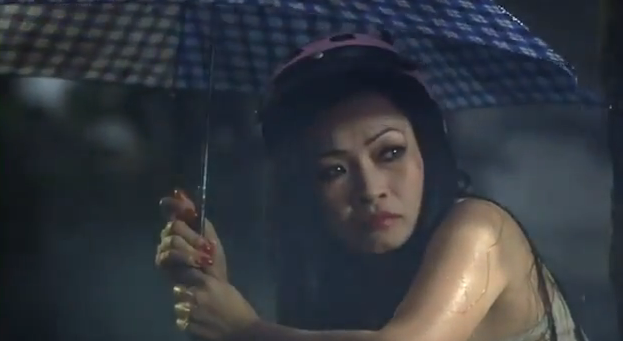

Indeed, paralleled to Lam and Khôi’s plotline is the entirely separate story of Hạnh, an aging female prostitute (folk singer Phương Thanh) and Cười (Hiếu Hiền) a mentally handicapped mute and garbage collector. Cười visits Hạnh repeatedly, only to be rebuked by both Hạnh and her pimp (Nsưt Kim Phương). After Cười finds a duck egg, which he plans to hatch and raise, Hạnh opens up about her innocent past in countryside in a duck farming village. Once the duck hatches, Hạnh and Cười form a strong relationship dissimilar from that of Lam and Khôi: instead of a sexualized partnership, it is merely platonic, asexually heterosexual.

Though different stories, Lam and Khôi’s and Hạnh and Cười’s have many similarities. Perhaps the most significant is the prevalence of violence. In fact, both Lam and Khôi’s and Hạnh and Cười’s stories end violently in scenes that closely mirror each other. Vũ repeatedly uses this technique throughout the movie. Where one character raises a knife to protect his lover, the other raises her knife against her pimp to protect a man she barely knows. Where one is beaten by a gang of men with sticks, the other carries a stick to beat off attackers. The effect is circular, akin to riding on the merry-go-round or déjà vu in the best of ways. It also highlights the interconnection of these two stories.

In this way, Lost in Paradise rises above the “gay film” genre. It not only focuses on the condition of gays in modern day Vietnam, but also the alienation and violence of urban life and the temporary connections forged between strangers that allows for survival. As a filmmaker, Vũ not only shows this through plot, but also through the visual elements of film. Sometimes within the same frame, we might see the working poor sleeping in deplorable conditions, while in the background, we city lights, shadows of passing cruise ships, trains. Symbols of progress are juxtaposed next to symbols of depravity. Such a layering of plot, commentary, and visuals as well as breakout performances (particularly from Phương Thanh and Hiếu Hiền) makes this film so haunting.

Lost in Paradise is a stunning achievement of contemporary Vietnamese cinema in an age of disappointing horror films and self-conscious directorial efforts. Thuy Linh recently criticized the Vietnamese movie industry, arguing that it is in crisis of “running out of ideas.” She proposes that Vietnamese directors focus on historicals instead of contemporary subject matters since these “have already been amply explored.” However, with Lost in Paradise, Vũ shows that there is plenty to explore. Directors must simply look for stories that have not yet been told: stories of the marginalized and the misunderstood. Lost in Paradise does this, and in doing so, it has not only become a cultural phenomenon, it also planted the seeds for substantial social change.

Watch Lost in Paradise here.

–

Eric Nguyen has a degree in sociology from the University of Maryland along with a certificate in LGBT Studies. He is currently an MFA candidate at McNeese State University and lives in Louisiana.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to share this post. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. Join the conversation and leave a comment! Have you seen Lost in Paradise? Do you agree with this author’s review of the film? Does it represent the LGBTQ community more accurately than past Vietnamese films with queer content?

Yes, this is a good film and Vu Ngoc Dang probably still held something back. I find the gay plot more honest and meaningful than the duck/prostitute plot. In terms of screenplay, if Vu Ngoc Dang focused on a fully-developed gay story and did away with the duck/prostitute plot, he might have created a better film technically, as well as something more meaningful to LGBT issues.

Also, an interesting note about Choi Voi: audiences often read a lesbian subtext in this movie. But the other day, Phan Dang Di, who wrote the script for Choi Voi, told an LGBT conference in Hanoi that he didn’t have homosexuality in mind. All he thought of and still does, as well as what he thinks artists do, is just to try to capture the human heart and experience, regardless of whether they are homosexual or not.