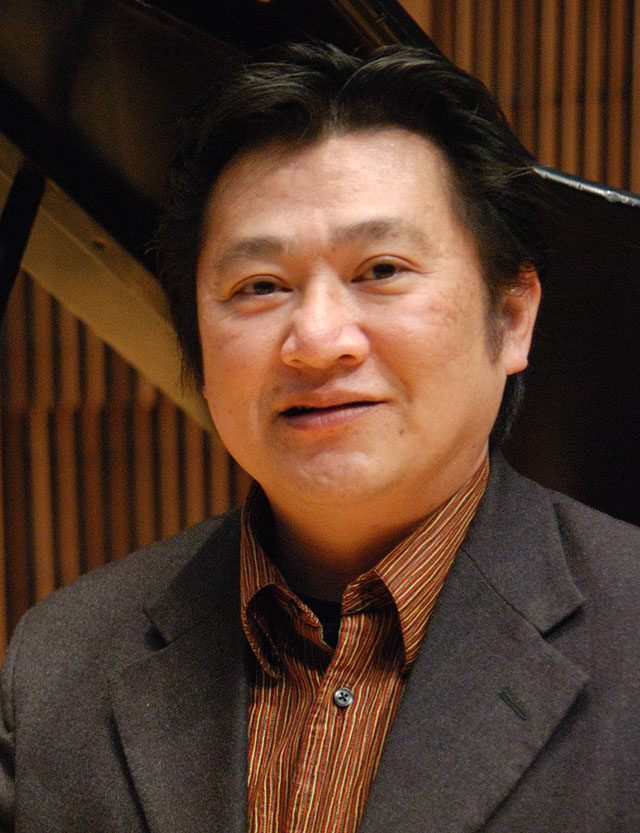

Born in 1962, Phan Quang Phục graduated with a degree from the School of Architecture in Hồ Chí Minh City in 1982. He settled in the United States in the same year and undertook music study first at the University of Southern California and then at the University of Michigan. He now serves as Associate Professor of Composition in the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University. Although he composes in what he calls the “Euro-centric” tradition, many of his works, including his most recent work The Tale of Lady Thị Kính, deal directly with Vietnamese aesthetics and stories. To listen to many of his works—including the ones described in this interview—please visit his website.

Have you subscribed to diaCRITICS yet? Subscribe and win prizes! Read more details.

Meeting the composer P.Q. Phan on a sunny weekday afternoon in Bloomington, Indiana felt like meeting an old friend for the first time. We are both graduates of the University of Michigan School of Music (now called the School of Music, Theatre & Dance), and we studied with some of the same faculty at the institution, albeit twenty years apart. We also share a serious interest in Vietnamese traditional music. He grew up with the music and, as a composer, incorporates elements of this music into his works; as an ethnomusicologist, I conduct fieldwork on and write about southern Vietnamese traditional music. Few in the United States—and even in Vietnam to a certain degree—find the nitty-gritty details of modal structure, ornamentation and historical performance practice worthy of extended discussion, so we had much to discuss.

We began with an examination of a handful of his works, including his opera recently premiered by the Jacobs School. In addition to this work, I asked him about Len dong [Raising Shadows], a work for string quartet premiered in 1996 that evokes aural elements of the lên đồng ritual space found in central Vietnam, and When the Worlds Mixed and Times Merged, a work for symphony orchestra premiered in 2000. He wrote this work in 1999 after a series of murders in Illinois and Indiana committed by self-proclaimed white supremacist. Instead of writing a work that overtly celebrated the new millennium, he wrote one that explored the complicated connections between disparate peoples operating in similar circumstances. Overlapping musical aesthetics permeate his works as he explores new forms of synthesis between the life he has lived and the music he has encountered.

CANNON: I’d like to begin by asking you about some works in your compositional output: the first is your recent opera, The Tale of Lady Thị Kính and the other one is your string quartet, Len dong.

PHAN: Oh, you’ve heard that piece! Where did you hear it?

CANNON: It’s on your website! And I listened to it and it was…

PHAN: This is trance music…

CANNON: When I listened to it, it transported me almost immediately. I’ve never been to a lên đồng ceremony before; I’ve heard hát chầu văn [music of the lên đồng ritual] performed before in staged settings, and I’ve read—do you know Barley Norton? Barley Norton is a British ethnomusicologist who’s written a book on lên đồng from northern Vietnam, and he has a DVD that goes along with it that is fantastic. It shows the mediums with red scarves over their heads before they go into trance. When they go into trance, they dance, throw out money, etc. I show this to my students and they…

PHAN: They freak out when they see the mediums dancing with fire! The composition Lên đồng is based more on Đà Nẵng culture, which is completely unorthodox, rather than Hà Nội culture, which is a little bit more orthodox. In lên đồng in the central culture, they’re familiar with some elements of Hà Nội culture, but they are more familiar with hát bội and ca Huế and all the music from Huế. They combine all this together. They do whatever they please as long as they accumulate the essence and move it forward each time. That’s even why they scream! The medium is also supposed to drink alcohol continuously to be in trance. And they do more than just dance—it’s very, very wild; however, I find this kind of music more scientific. It’s actually, most of the time, in a cyclic form. It reminds me of gamelan music: in each cycle, it evolves and moves faster. I find it fascinating too because the essence of cyclic form is absolutely not derived from Chinese traditional music. It comes from the Polynesian area; this makes me feel like chầu văn has to be older than any other musical art form in Vietnam. When you think about this, it is to worship in a kind of “pagan” way. The combination of paganism and the form makes me feel like its origin is detached from Chinese music in many, many ways.

Len dong performed by the Kronos Quartet

Recording provided courtesy of P.Q. Phan

CANNON: In your opinion, how is chầu văn more scientific or calculating?

PHAN: In my opinion, chầu văn is a lot more calculating compared to a lot of other kinds of music in Vietnam. I should not say entirely in Asia, but I’d say in Vietnam. It’s a lot more calculating because it serves a particular function. Every time they have a lên đồng or đồng bóng, they know that the event will last at least 30 minutes, right? They know that, so they must calculate to provide music for the entire event. The same thing is found in the music of India. They know for sure that when they give a concert, they have to calculate how much time they want to entertain their listeners; because of that, they always make things very, very simple at the beginning and a lot more complex toward the end. Chầu văn is almost like that.

CANNON: Does the music provoke an emotional response through “calculation”?

PHAN: Exactly, because chầu văn doesn’t respond to the dancer. It provokes the dancer and therefore it has a totally different function. It’s almost like Beethoven’s Ninth, which provokes the listeners as well, but we do not perform that piece based on the listener’s demand. Sentimental music on the other hand is performed based on the listener, but never broadly based on what you want to provoke for them to understand. In entertainment music, you worry about whether the audience will be bored or not without thinking about what you really need to do—your responsibility.

CANNON: In your program notes for The Tale of Lady Thị Kính, you talked about the increasing complexity found in the work and how the music you wrote becomes more complex in terms of orchestration, timbre, harmony, etc., from the beginning of the piece to the end. How does that fit in with this notion of calculation?

PHAN: First of all, the concept of increasing complexity comes out of the main character. The main character herself is a transcendent character from the simplest being to the most complex being. Complex here is not complex in a Western way of thinking, but like a superior form. At the beginning, her origin as a Vietnamese woman is told, so the music is actually derived 95% from a hát chèo tune. This indicates originality and is as authentic as it could be; toward the end, the essence of hát chèo has completely gone away. The melody at first is very traditional, and toward the end, the melody itself is more a “cultivated” or Euro-centric construction. The harmony at the beginning mainly uses a pure pentatonic melody, but toward the end, it is a combination of two different pentatonic scales and incorporates spectralism as well. (Interviewer’s note: Spectralism is a compositional technique where composers generate material not through harmony or melody but through combinations or groupings of sounds sometimes described as “splashes of sound color.”) I don’t expect my listeners to understand it, but I think that’s the beauty of the composition.

CANNON: Can I ask you about the influence of philosophy on Thị Kính? I’m thinking back to your program notes and your description of the presentation of both Buddhism and Confucianism and—I don’t necessarily want to say the conflict between the two but—the interaction between the two and how you try to bring that out musically in the opera?

PHAN: Musically? That is tough. When I undertook the process of reinterpreting the play, I had a lot of questions for myself. If you go through the entire repertoire of hát chèo, including plays like Chu Mãi Thần, Lưu Bình Dương Lễ—let’s say you take those two and you compare them to Quan Âm Thị Kính—why is it that every single script in hát chèo talks about the beauty of the role of man and how they achieve greatness through the teachings of Confucianism? Looking at the script of Quan Âm Thị Kính, you read back and forth, reading every single word in the script through many different versions—and Vũ Khắc Khoan’s is, I think, one of the good versions—and you realize that, first of all, there’s no man in there that is good, even Thị Kính’s father. If you don’t talk about the greatness of man, you more than halfway deny the teachings of Confucianism, right? Only one line of Sư Cụ in there says, “If I sacrifice one, I may save thousands.” Just one short line proves that he’s a hypocrite. The word hypocrite here is not exactly anti-Buddhist but teaches Buddhism at the higher level and teaches people that you don’t need to follow a temple or a monk for you to achieve the highest level in Buddhism. So writers did not really bad mouth the monk but just said that the deep philosophy in Buddhism is what you should follow.

In addition, when you read through the entire story, you realize that there’s not even one line in the script to curse Thị Mầu. In Chu Mãi Thần, it’s different. They’re so many lines that say bad things about Xúy Vân but not in Thị Kính; it makes you think. Do they actually endorse her actions? If you put all this stuff together, I ask myself: was this story actually told by a man? I sort of doubt it! When I put all the strains together and reconstruct it to allow me to set the music, I set a kind of music that, in a way, musically will bring out each character to paint them well. Let me see, ask the question again, it’s really difficult. How do I portray this in music?

CANNON: How do you portray these Confucian and Buddhist ideas musically?

PHAN: Okay, in Buddhism, the highest level of Buddhism is transcendent, so musically speaking, I write many more ascending lines. Toward the end, when Thị Kính reaches Nirvana, then everything moves upward. The part that I’m very proud of is the aria when she’s taking the baby to marketplace. She’s at the temple and when she finds the baby there, you hear the temple gong. In the temple you don’t use high-pitched sounds; they prefer something deeper. As she’s leaving the temple, taking off to make the market her new home, then the sounds of the temple gong start to fade and are replaced with bells and the glockenspiel. The bells are tinkling and more fitted to the marketplace than the temple. I add drums too to make it more like the marketplace. So when she moves from one environment to another one, the sacred area turns into a more vernacular area. At the same time, though, the ascending sounds represent the concept of transcending in Buddhism.

In the teachings of Confucianism, the deep part of Confucianism is class and hierarchy. In the music, it’s not necessary only to paint Confucianism but also to paint the realism of the society. I therefore start to give each character a different musical construction. For example, a less educated person will likely sing in a mono-rhythmic way. The melody line is very, very simple. For the more educated person, on the other hand, the structure is a lot more complex rhythmically and a lot more melismatic. So my reflection on Confucianism perhaps involves the social classes in the play more than anything else, but I must confess that I did not do that to reflect Confucianism but mainly to make the play more realistic. I portray the female characters, musically speaking, in a livelier, more inspired, and more attractive way. Maybe to represent the female value is part of my subconscious, and this is a personal reflection to say that I don’t believe in Confucianism.

Opera is incidental music; it’s not abstract music. For my current project, I am writing a requiem based on a Theravada text. I use numerology, and I can explain that very clearly. But in the opera, I cannot use numerology because the opera’s not an abstract piece. I make it as abstract as it can be, so I try to make a connection between the micro and macro relationships; only that much I can do.

CANNON: Can I ask you speak more generally about expression either in this work or in another work? How do you musically express a character in a story you tell through a composition? How do you use music as personal expression?

PHAN: You know, the student who sang the role of Thị Kính told me once that the aria sung when she carries the baby to the market place was really difficult for her. I said, “why is that?” and she responded, “well, because I don’t know exactly how to express this.” And I told her, “yes, it is very difficult for me too because I try to paint a figure that who’s half sacred and half secular.” In this situation, Thị Kính cannot be angry, she cannot be sad, and she cannot curse. She’s supposed to be calm and express herself in the most discrete way, but accept her state and her spiritual consequence. I try to craft a tone where she is not weeping, but I cannot make her happy. Her melodic expression is like that since the beginning; her melody is constructed in a way that she can foresee the future when she accepts the baby. She takes the baby and goes to the marketplace, where she knows that she’s going to die. She accepts it very quietly, but not in an angry way.

It’s kind of funny—the end of the aria features the phrase “to live and grow.” The director David Effron told me at one point, “well, you know, to live and grow, we should put that up an octave higher.” Initially, I said, “yeah, okay, you can do that,” because I’m a very easy person. Later, I was not happy about this change. When Thị Kính sings the word “grow” toward the end, it’s not for her to literally grow. “To grow” actually represents death in the way that she grows into a different form. That simple line reflects that I believe in Buddhism. That means you take everything in the very calm way and you aren’t overly emotional about it. And I find that it’s one of the most difficult things for the singer to express. A previous aria sung before she becomes a monk is a lot easier to sing, because in the latter aria, the text contradicts the music.

In terms of my expression, I embed truthfulness into each character. For example, Thị Mầu is supposed to be thirteen years old, and I find that a coloratura singer is very well fitted for this role. To express this high spirit in the higher range represents who she is. In contrast, when Mozart’s Queen of the Night sings, she represents a particular godly anger; a godly anger is different than a dramatic soprano. In Vietnamese culture, when a young woman does something in a very high-spirited and not well-thought-out way, she tends to sing like a bird. Or, before Nô the uneducated servant comes out, there’s an orchestral introduction that plays an unsteady and asymmetrical poking rhythm. That asymmetrical rhythm represents a person who is not articulate. When Thị Mầu and Nô share a love song, Thị Mầu’s part is very beautiful and his part is very awkward, so those are some things that I express through the music. But, again, with an incidental work like this, personal expression is subservient to the character.

CANNON: What about personal expression in other works?

PHAN: In other abstract pieces, have you had a chance to go and listen to my AC/DC? AC/DC is as deep as I can be when I make the East meet the West; nobody would necessarily understand this. The work is divided into two very clear and equal lengths. One is in alternative form—the AC, the “alternate current”—and the other is in the very direct form—the DC, the “direct current.” The “alternate current” represents me switching my personality between my personal identity of whom I’m supposed to be—in the way that I’m not exactly torn but being displayed between two very different cultures. With the quick changes of mode, the structure represents being almost confused, in a way. Musically speaking, I feature a pentatonic tune in equal temperament played on top of spectralism, so you have the Southeast Asian sound and you still have the modern Western thinking put together. They interact in a more agreeable way and support each other. This abstract piece allows me to express who I am at a deeper level without depending on incidental characters, like in the opera.

CANNON: Also in regards to expression, I want to ask you about the piece When the Worlds Mixed and Times Merged, because this work is very powerful. I like many of your chamber works but in this, you’re working with a larger ensemble. This is interesting to me because you were influenced by an external event, something that happened in the Midwest.

PHAN: Yes, this external event confirmed my internal thinking. The piece was commissioned as part of the millennium celebration, and I was planning to do something very jubilant. But then, during the summer before the millennium when I experienced this event in my hometown, I changed my mind. That same night, my students and I went to Chicago to watch the fireworks, and on the way back, we heard about this news. On the same day we went up there, there was a shooting spree; that gave me more to think about and made me more confused. I was confused because celebration and fear—or it could be something else—could happen at the same time. Instead of being angry about it, I think I tried to explain why it happened. It happened because of different times and different worlds mixed together, and that’s why things happen.

When the Worlds Mixed and Times Merged performed by the Indiana University Philharmonic Orchestra

Recording provided courtesy of P.Q. Phan

CANNON: Did you try to explain it to yourself through the compositional process or were you trying to explain it to a broader audience at this time—the new millennium?

PHAN: It was a personal reconciliation. You reconcile a personal thing and at the same time, you represent that and hopefully share it. It’s better for people to perceive my frustration more than my anger. I was frustrated because you cannot really blame this kid. Of course you can blame him personally, but you can also understand that this kid is as confused as I am. It just happens that one is in a controlled situation and one has an outburst. But what happened between this kid and what happened to me is because times merge and worlds merge, and nobody’s ready for it. And I don’t think anyone’s still ready for it. For me, to do this piece is to express confusion more than anything else, but I don’t necessarily propose a solution; there’s no solution. Does that make sense to you?

CANNON: It does.

PHAN: I think if you listen to the work, you may enjoy the first two minutes of it. You remember that?

CANNON: Yes, you try to depict court music, correct? I also thought it sounded like nhạc lễ a little bit.

PHAN: Yes, in particular, this nhạc lễ is from the Thét nhạc [a form of Đại nhạc]. And what it does is to open the day in the court. The music itself is actually Confucian music; it is played to get rid of the evil spirits. After this, the music combines pentatonic scales and spectralism. Then you hear this really cheerful music, but it is quickly interrupted by new music. In other words, you have big sections of Vietnamese music, big sections of Western music; you have a quick section that alternates between a white stripe, a black stripe, a white stripe, etc. so they go back and forth very quickly. It’s the musical equivalent of flipping the cartoon—you flip the pages very quickly and you see an image emerge. I think it works in my mind more than in the listener’s mind. Most composers tend to freeze time—a second for us could last an hour if we wanted, but to the listener, a second is a second. When I flip like that very quickly, I can hear the differences, but maybe a regular listener cannot understand it. So, I flip back and forth, and after that section, I have a very long and pointed section. This section is a more personal reflection on the event. The event was, at first, more like a physical painting—the black stripe and the white stripe. The personal expression follows it, and toward the end, it flips back again to the painting. The last two minutes says that, well, it was what it was; there’s nothing you can do about it.

Part II to follow…

–

Alexander M. Cannon is Assistant Professor of Music History and Ethnomusicology in the School of Music at Western Michigan University. His research investigates the changing nature of đờn ca tài tử, a “music for diversion” in contemporary southern Vietnam. He is published in the Journal of Vietnamese Studies and the journalEthnomusicology; when not writing and teaching, he endeavors to improve his skills on the đàn tranh zither and đàn sến lute.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to share this post. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. Join the conversation and leave a comment! Now that we’ve learned how P.Q. Phan musically expresses a character in a story through his compositions, how do you use music as personal expression?