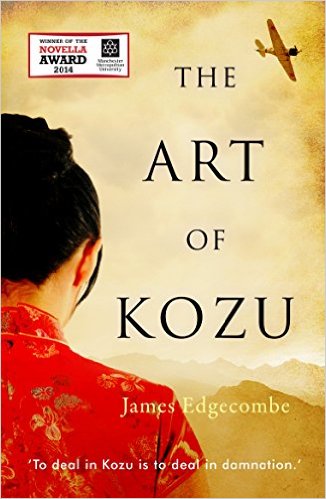

Eric Nguyen reviews James Edgecombe’s new novella The Art of Kozu, which won the 2014 MMU Novella Award. By narrating the life of a Japanese artist living in Paris and Japanese-occupied Vietnam, Edgecombe’s debut work asks the reader to consider more difficult questions on the themes of race and art.

In 1940, Japan invaded Vietnam to create a blockade against China in the Second Sino-Japanese War. The invasion marked a chapter in Japan’s effort to exert its influence in East Asia under the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The Japanese military occupied Vietnam until the end of WWII in 1945.

It is an interesting era in Vietnamese history that is rarely explored in fiction, overshadowed by the Vietnam War, which remains largely in American consciousness as a narrative of well-intended but ultimately failed heroism. Vietnam, though, is more than a war and it is always refreshing to see stories that look at different aspects of Vietnamese history.

James Edgecombe’s debut novella The Art of Kozu—winner of the inaugural Manchester Metropolitan University Novella Award—might fall into this latter category of literary works that are about Vietnam but not about the War, though at first glance the book has little to do with the Vietnamese experience.

In Part I, we meet Yuichiro Kozu, a fictional Japanese painter in Paris, who mimics the works of European artists as he tries to make a name for himself. It is the classic artist’s story of moving to a metropolis to become famous: “Yuichiro…fled Hakodate to live and paint in Paris, filled with ambition—the dream—to become a great painter—the greatest Japanese painter in Europe.” At best, however, Yuichiro is met with indifference and makes his income making souvenir sketches in a “Japonisme” style, cashing in on the European penchant for all things oriental.

When he finally makes a breakthrough, his brother Juno is the first to criticize: “I’ll admit the carriage is technically proficient,” he says of Yuichiro’s painting of a nude Japanese woman on a train. “But the girl, that supposed Japanese girl? She is a monstrosity.” According to Juno, Yuichiro is only mimicking European painters; there is nothing inherently Japanese about his art. To show Yuichiro what he means, Juno takes him to the morgue, where they steal the dead body of a Japanese woman and bring it home for examination.

“To deal in Kozu is to deal in damnation,” is the tagline on the book’s cover and indeed this is a theme that continues in Part II, though the setting differs significantly. Fast forward a few decades and Yuichiro is a propaganda painter for the Japanese Imperial Army in Japanese-occupied Vietnam.

In the final days of the Japanese occupation, Yuchiro is living reclusively in Cholon where he mentors a Vietnamese boy, Trau, who, he claims, is the reincarnated soul of Van Gogh. In Trau, Yuchiro sees himself as a struggling young artist. Trau even becomes a model for Yuchiro, though he never completes the painting as Cholon comes under siege and Yuchiro is escorted out of Vietnam, though, not before he paints one final picture for a Japanese major that eventually damns him, and the grotesque scenes of Part I comes full circle.

For a novella, The Art of Kozu spans epic proportions as it moves between countries, continents, and time periods. Edgecombe is nothing short of ambitious in this meticulously detailed, well-researched story. His writing is evocative of both place and time:

“Dusk dropped over the Chinese City. Blackout regulations kept the canal and its warehouse in darkness. We made slow progress along the route de Binh Bông, passing peasants heading back to their hamlets beyond the city limits. In their black pajamas and against the white glow of the road’s dirt, they resembled spent matchsticks. To our left the paddy fields and marshes of the countryside washed up against the dyke, a humming thundercloud of bullfrog songs.”

Edgecombe has the eye of a painter and translates colors and mood easily onto the page. He is also masterful in the building of plot and tension and at times has the macabre tone reminiscent of Poe. In a scene involving a drunken night in the Catacombs of Paris, Edgecombe writes: “Bones, tens and thousands of them, were stacked piles jutting out from the cavern walls. Layer upon layer upon layer: their numbers meaningless.” Reading this, one cannot help but recall “The Cask of Amontillado.”

Yet in between the thriller-like pacing and evocative descriptions, Edgecombe asks important and complex questions about art and race. For instance, what does it mean to make art inherently of one’s people? How can a Japanese artist, like Yuichiro, not paint “like a Japanese”? Does art have an inherent race or nationality to it? If so, what qualities can we point to argue this?

To explore this further, Edgecombe adds the nuance of artistic intent. “One can be forgiven for thinking the soldier in your painting Japanese,” says the narrator, an art dealer, pointing to one of Kozu’s propaganda painting, one, which we soon find out, is modeled after Trau donning a Japanese soldier’s uniform. Given this, is Kozu a subversive artist, or is he re-appropriating Vietnamese bodies for Japanese colonialism? Readers never get an answer from the artist, and instead, we are left with the narrator’s reading. The metafictional quality of the text adds a layer to its themes.

To explore this further, Edgecombe adds the nuance of artistic intent. “One can be forgiven for thinking the soldier in your painting Japanese,” says the narrator, an art dealer, pointing to one of Kozu’s propaganda painting, one, which we soon find out, is modeled after Trau donning a Japanese soldier’s uniform. Given this, is Kozu a subversive artist, or is he re-appropriating Vietnamese bodies for Japanese colonialism? Readers never get an answer from the artist, and instead, we are left with the narrator’s reading. The metafictional quality of the text adds a layer to its themes.

The themes Edgecombe explores is perhaps even more relevant today where the inequalities of race is finally becoming highlighted in the national media and as writers try to address the racial other in their works. In a recent review of Joyce Carol Oates’s The Sacrifice, a novel concerning interracial violence, Roxane Gay wrote: “To write difference well demands empathy, an ability to respect the humanity of those you mean to represent.” Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda also addressed the writing of the racial imaginary in an essay published in Literary Hub. The problem of writing across race is usually a lack of empathy resulting in characters of color becoming one-dimensional caricatures or else mere props.

The Art of Kozu avoids this issue. Edgecombe writes from a place of history and empathy, while exploring ideas about art, race, and authenticity. While, of course, his characters are at times despicable, they are always complex and human, wrestling with meaning and survival. The Art of Kozu is both particular and universal. One could only wish for a longer story.

Buy the book here.

–

Eric Nguyen has a degree in sociology from the University of Maryland along with a certificate in LGBT Studies. He is currently an MFA candidate at McNeese State University and lives in Louisiana.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment!