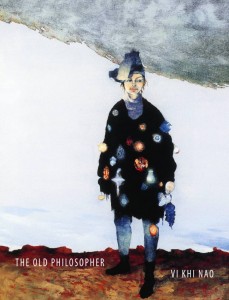

diaCRITIC Eric Nguyen reviews Vi Khi Nao’s experimental poetry book, The Old Philosopher.

At its worst, experimental poetry can be unartful and careless, obfuscating whatever meaning and pleasure that might dwell in the text. At its best, it can call into question language, form, power—anything it pleases, really, through the act of making what we know of poetry new. Vi Khi Nao’s The Old Philosopher comfortably belongs in the latter category. And her subject? Many—Vietnam, violence, sexuality, love, art. But perhaps the most prominent subject is god. Indeed, there are many allusions to biblical and religious texts and stories in this debut collection. Despite this, however, Nao’s god is neither religious nor spiritual. Instead, her god is an idea, and it is this idea of god and how it could exist in our contemporary moment that she explores.

The title poem situates the readers to Nao’s ontological project. In thirteen lines, Nao paints a scene of birds—“approximately four thousand/two-hundred and forty five” of them—released from the trunks of three cars. As they are freed, one “like an old philosopher/Socrates perhaps” stays behind, “walking back and forth on the gray carpet.” The speakers in this collection’s poems are like this old philosopher, this odd bird, observing this new world, a newly-birded world.

If that’s a strange image, it’s because the book is populated with such strange, surreal imagery, analogies, metaphors, and personifications that navigate between the playful to the sinister, all of which are equally startling. In “AA Meeting for a Limestone,” a rock sits in on a solitary “preventative AA meeting” so it “can talk shit about [its] pain, delirium, [and] lack of total control.” Two poems later, in “How Can Something So Unmoving Move Everything Around It,” the image of a rock is deployed differently to describe the human heart, like “Mount Hood…which lies/in Oregon like an alligator.” In the first poem, the rock has sassy voice and attitude mocking human folly (the poem’s last line is “See ya around, pancake faces”); in the second, the image of the rock stands for not only the stoic coldness of humanity, but—with the final word, “alligator,”—its danger as well.

Nao’s imagery works best when they are situated within the familiar. This is especially the case in poems that are seemingly autobiographical. In “My Socialist Saliva,” the speaker is riding with her mother on a motorcycle in Long Khanh:

My mother rode me on land coated with rambutans

Rambutans were like little ball hearts growing red hair

The earth of Long Khanh was swollen with such cardiovascular beauties[.]

The associative leaps in images move from the natural (“rambutans”) to the grotesque (“little ball hearts growing red hair”) and back to something not quite natural, surely unexpected, but beautiful nonetheless (“cardiovascular beauties”). It’s far from the literal world we live in, but the juxtaposition of the ugly and the beautiful—or perhaps seeing the ugly in the beautiful—speaks of our own messy world. Such handling of imagery suggests one of either two ideas of god: its very nonexistence or its malevolent nature.

The idea of the nonexistent god appears in the first poem, “dear god I am god.” Halfway through this short poem, this line is repeated, followed by “i am am washing myself in dew.” This “god” is seen in the next poem (“Fog”) as “a child/who pretends to pray” who is “a beautiful version of daffodil twirling in dew[.]” Placing these two poems in this order, with their continuation of theme and diction, Nao portrays god as a playful identity, something one can put on and perform. Tellingly, “dead god i am god” ends with “performance art as identity” and “Fog” includes the phrase “make-believe childhood.”

In contrast, Nao also presents the idea of a cruel god in poems like “The Day God Smokes My Grandmother.” Here, the poet ups the surrealism and imagines the speaker’s family members as cigarettes, “made of human tobacco & Long Khanh’s red earth &/ Bed sheets as long/as a rubber tree.” When an uncle steps outs for a smoke of his own, the speaker observes wryly, it’s “a cigarette smoking a cigarette.” The poem continues with god smoking each of the speaker’s family members, stopping at her at the end, where she concludes self-deprecatingly: “God doesn’t like to smoke me. /I smell too much like a conflicting/Mixture of lavender and walleye.” “The Day God Smokes My Grandmother”—a meditation on death—is exemplary of Nao’s unique ability observe the human condition with nuanced astuteness; to Nao, existence is very terrible but it is also very funny.

Appropriately, in “Biblical Flesh,” Nao asks: is it you who gets fucked or is it God?” That is, are we playing god (the word “play” heavy with all the connotations of both theatre and deceit) or is god playing with us? That these two ideas are present in equal parts in The Old Philosopher suggests that the answer doesn’t matter. Nao’s speakers are resilient. One gets an inkling that despite what happens or has happened to them in these poems, their lives continue. Notably, Nao has the tendency to deflate the worst of human experience. In “Today I Lost My Hat,” Nao writes a timeline of the day the speaker’s grandmother dies. Keenly, she writes, “the sun did not show up for work…there was much dying to do.” This is followed by a mundane observation: “Lunch: Rice tasted like raw goat milk.” The horror of death and the banality of life collapse at the end in a one-line stanza, where the speaker exclaims sardonically, “How death makes one suffer!”

The Old Philosopher is a playful celebration of life, following the adage, “Don’t take life seriously; no one gets out of here alive.” While those inexperienced with nontraditional forms of poetry might balk at Nao’s use of space, her leaps of thought, and her, at times, dense maximalism, Nao is a skillful writer—a literary offspring of M.C. Escher and Salvador Dali yet something uniquely her own—whose wisdom and ability to continually surprise, poem after poem, makes the reading worth the effort.

Buy the book here.

The Old Philosopher

by Vi Khi Nao

Nightboat Books

80 pages

$15.95

Also included here is a poem from The Old Philosopher:

THE DAY GOD SMOKES MY GRANDMOTHER

God pulls my grandmother

Out of a finely made cigarette pack

Made of human tobacco & Long Khanh’s red earth &

Bed sheets as long

As a rubber tree.

My family – all twenty of us – my grandmother,

My cousins, my aunts and uncles

All lie in a large cigarette cot

Called a bed with tinfoil bed sheets pulled to our chins.

We lie in rows on top of each other.

Over soft bones.

While my uncle steps out into my grandmother’s grapevine.

He withdraws a cigarette from

His jean pocket and drags a smoke.

A cigarette smoking a cigarette.

Meanwhile, God pulls my grandmother

Out of her cigarette bed.

She is wedged between my first aunt and my second aunt.

He thumps her head against the wooden lid of the well &

Lights my grandmother’s head up.

A fluttering of smoke is steamed out of her toes.

God inhales and exhales the soul of my grandmother

Until she withers and becomes an accordion of ash.

Then God flicks the rest of my grandmother across

Our neighbor’s spinach garden.

God and my uncle take turns smoking.

While God finishes nearly a pack of us – one by one –

My uncle still ponders over his last three,

Sitting in their nearly empty compartment.

My uncle stares into the ashtray of his hand

And sobs until his hand becomes soot.

We stay inside of our floorboard cigarette case

And ponder when God is going to

Develop lung cancer

From smoking us.

Not long ago, in Long Khanh,

God handrolls his own cigarettes.

God licks the sides of our bed sheets

With his wet tongue.

And rolls me into a thin tobacco-burrito.

God smokes my cousin first, the one who was run over by a train

In my uncle’s backyard, near my grandmother’s grapevine.

God, the chronic smoker, likes his cigarettes

Aged three.

Short and stumpy.

God doesn’t like to smoke me.

I smell too much like a conflicting

Mixture of lavender and walleye.

–

Eric Nguyen has a MFA in creative writing from McNeese State University and BA in sociology from the University of Maryland. He has been awarded writing fellowships from the Lambda Literary Foundation and Voices of Our Nation Arts (VONA).

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing!

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment!