Contributing Editor Sheila Ngoc Pham gives an encompassing look at graphic novels by Vietnamese diasporic comic artists/memoirists from different countries—Thi Bui and GB Tran in the U.S., Clement Baloup and Marcelino Truong in France, and Matt Huynh in Australia.

On our morning walk around the base of Uluru in central Australia, the guide pointed to the drawings still visible on its immense walls—and as we looked at those images, I felt myself being transported back into the deep past. After all, drawings have been used since time immemorial to entertain and pass on knowledge, with Aboriginal rock art being among the earliest predecessors of a more contemporary form that continues to flourish: comics.

Comics have since undergone many iterations—most recently including ‘graphic novels‘—and still continue to draw on the same fundamental power the First Australians wielded, as have many others over time. This suggests that there is something inherent about drawing, including comics, which mirrors the way we think. It’s what Art Spiegelman suggested when speaking on The Big Interview: “We think in little bursts of language and strong images, high definition images – those images need to be understood and dealt with, not suppressed… It’s a good diagnostic tool for where the problems are.”

If we are to think of comics as a kind of ‘diagnostic tool’, it’s intriguing to consider the many works by Việt kiều artists and what they might reveal about our ailments. These works are important contributions to the growing canon of Vietnamese diaspora works, with comics sitting right at the intersection of both literature and art. The growing collection now available in English includes: Vietnamerica by GB Tran (2010); Ma by Matt Huynh (2013); Such a Lovely Little War by Marcelino Truong (2016); The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui (2017); Saigon Calling by Marcelino Truong (2017), Vietnamese Memories: Leaving Saigon (2018) and Vietnamese Memories 2: Little Saigon by Clément Baloup (2018).

Comics as a form of storytelling have become increasingly complex, with multifaceted stories about history and identity now commonplace. The works of these Việt kiều artists present perspectives drawn from different ages, classes, and personal circumstances. Together they show us the multitude of ways we might enter into our histories and come to terms with how we came to be in the places we are. In an essay by comic artist Pat Grant in his comic book Blue, he talks to fellow Australian comic artist Shaun Tan who believes that:

Comics are almost always about memory, about looking back, about making sense of the past.

Tran and Bui are Vietnamese Americans and their books focus on their family histories in both Vietnam and America. Huynh is a Vietnamese Australian who now lives in the United States, and Ma focuses on a family in a refugee camp off the coast of Malaysia after the war. Meanwhile Truong’s memoirs are about growing up in the ’60s and ’70s in Saigon and London, among other places. His books were originally published in French with the titles Une si jolie petite guerre (2012) and Give Peace a Chance (2015). Baloup is a French comic artist and, like Truong, has a Vietnamese father. He reveals a bit of this personal history at the start but otherwise opts for reportage of the Việt kiều in France in his first volume, and the Việt kiều in the United States in his second volume. Baloup’s first two books in his ongoing series about the Vietnamese diaspora around the world were originally published in French with the titles Quitter Saigon, mémoires de Viet Kieu tome 1 (2013) and Little Saigon, mémoires de Viet Kieu tome 2 (2016).

All of these works span the turbulent last century of Vietnamese and world history, the stories being complementary as well as overlapping. It begins with French colonial administration and the struggle for independence, through to life during the war and thereafter—when we became refugees, migrants, transnationals, travelers. One important aspect found across all the books is the attempt to engage with the broader political and historical contexts which shaped the immediate lives of individuals and their families. Each work tries to solve what Bui describes in the preface to her book as “the storytelling problem of how to present history in a way that is human and relatable and not oversimplified.”

As it turns out, it’s a problem comics can solve. Comics are a form in which the narrator can look both backwards and forwards simultaneously while straddling perspectives, nations, continents, and eras—all while describing past events that are necessarily fragmented and imperfectly recalled. Our fraught histories are pieced together from oft-repeated stories, overheard fragments, conversations, mysteries, scarce artefacts, first- and second-hand accounts. Reconciling with the past is a struggle when we exist so far from the epicenter, often shouldering the burden of family sacrifices. This is a familiar state for many of us as we examine our diasporic identities at close quarters, and struggle to view it as a coherent whole. One reason for this is what Tran writes in Vietnamerica:

My family’s unwillingness to share the most basic facts was as much to blame as my decades of disinterest and insensitivity.

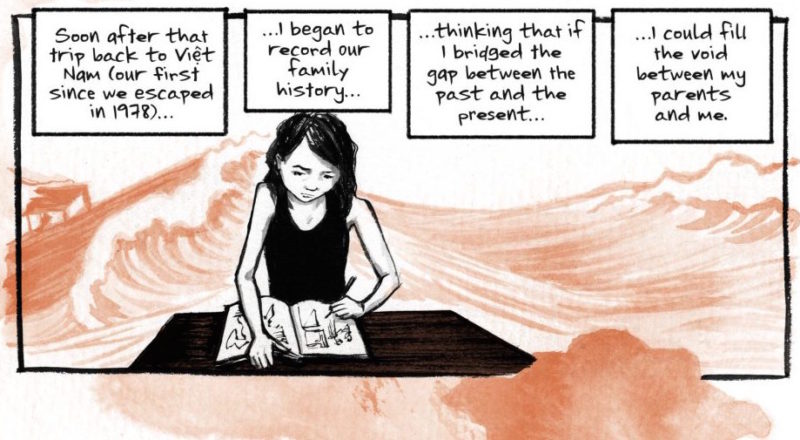

Naturally, however, there is curiosity, in part driven by the challenge of how the subsequent generation raised as part of the diaspora can insert themselves into the first generation’s narrative—even finding common ground. Bui explains that she started this journey of recording her family’s history to “see my parents as real people … and learn to love them better.” We can also frame the refugee experience in terms of intergenerational trauma, which is why Bui found creating The Best We Could Do “a form of therapy.”

This is where the Vietnamese American comic books in particular share similarities with a work such as Maus by Art Spiegelman. In Maus, a version of Spiegelman himself is a character in the story, a son trying to make sense of his father’s experience of the Holocaust. The seams of the creative process are in full view for the reader, and Spiegelman’s act of memoir is a self-conscious one. Similarly, Bui’s and Tran’s stories commence with their adult lives, delving into their family histories and seeking answers to questions.

Navigating this terrain is necessary work for many of us, particularly if or when we have our own children and consider how much they need to know about their antecedents. Bui is the most explicit with this aim, beginning her book with scenes from the birth of her first child. In those powerful early moments of life, she gains profound understanding about her own mother and her family’s history.

*

Each comic comprises infinite artistic choices impossible to take in at once: the thickness of strokes, the lettering, the positioning of panels from page to page, and the drawing styles. Huynh opts for monochromatic black-and-white, his characteristic brush strokes potent with big emotions. Bui’s is a limited palette of black and rust tones and this discipline of color contributes to the story’s coherence. Meanwhile, Truong takes a more classic European approach to coloring that lends his works a rather beautiful nostalgic quality. Baloup’s watercolor palette shifts between pared-back monochrome to full color moments, and Tran’s book is the most dazzling of all in its use of color.

In stark contrast to the multi-layered and panoramic nature of the Vietnamese American accounts, Huynh’s work is an intimate close-up which takes small and slow steps, much as the baby in the story does. Ma tackles one of the best known narratives of the Vietnam War: the mass exodus by boat and the refugee camps throughout Southeast Asia.

These are the stories many of us heard over and over again throughout our childhoods. In The Best We Could Do Bui dedicates part of the narrative to the escape by boat and her family’s time on Pulau Besar; Huynh zooms right in, mimicking the slow and uncertain waiting of the refugee camp. Unlike the other comics, however, Ma is a more impressionistic and poetic rendering rather than a memoir per se. The story is based on his family’s experience on Pulau Bidong before he was born, and their names appear at the end of the book. The island camp off the coast of Malaysia is the same one my own family passed through along with an estimated quarter of a million Vietnamese. As Huynh explained to Peril magazine:

This is a comic book about experiences spoken in hushed tones, as a way of understanding my parents, how I was brought up, my values, and detailing events before I was alive. And so, ‘ma’ – an active consciousness of a gap in memory, understanding, time, space.

Ma is a multilingual word: in Japanese it means ‘interval’ which is the ‘gap’ Huynh refers to. Inflected with different tones in Vietnamese it means both ‘ghost’ and ‘mother’. Ma serves as a stand-in for all refugees and this work was also created, at the time, as an urgent response to what Huynh refers to as “the very recent demonization of asylum seekers and boat people in Australian politics and media.”

In Baloup’s second volume, Little Saigon, he introduces readers to a beautiful older woman named Anh. A resident of San Francisco, she meets Baloup in San Jose, a key city for Việt kiều in America. We soon discover that Anh, like Huynh’s and my family, also stayed on Pulau Bidong for a time after the war. Panel by panel, her time in the refugee camp unfolds, and, despite having heard about Bidong for as long as I could remember, I was under-prepared for her shocking account. The visceral and harrowing account of her experiences on the island made all the more vivid and, well, graphic because of the images.

Alongside Anh, Baloup meets many others on his travels in America—including Asians from other diasporas—and his work demonstrates the value of reportage, going far beyond personal history and covering a broad range of stories that gives the Vietnamese diaspora its shape. Yet there is no suggestion that this shape is definitive and, if anything, he subtly shows how fluid it is. In the history of the world, we’re new to being scattered, and Baloup explores how these new homes we find ourselves in remake us. As Antoine, a friend of Anh’s, says:

We’re in America, here! The land of opportunity, the land of dreams. We have to enjoy it…right?

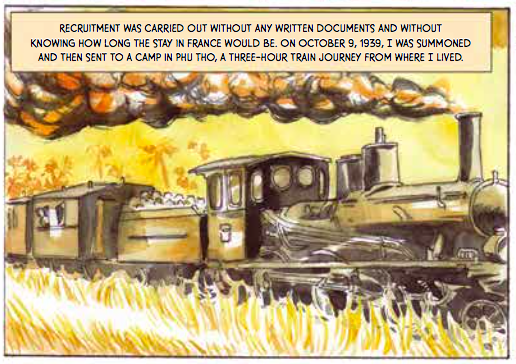

Bui’s and Tran’s books include the struggle for independence from the French and the lead up to what we now call the Vietnam War, but Baloup’s Leaving Saigon tackles the French colonial period head on. Through his reportage we learn about the Việt kiều in France, who have been coming into the country over a long period of time, not just arriving en masse as refugees and sponsored migrants. In Leaving Saigon the earliest histories of the Việt kiều are particularly fascinating, including almost forgotten histories about Vietnamese indentured laborers during World War II, a stark illustration of what it meant to be a French colonial subject.

Another intriguing chapter of Leaving Saigon focuses on an area of France known as Vietnam-sur-Lot or ‘CAFI’. The camp was set up after the French evacuation of Indochina, built on military land. At one point, CAFI housed up to 1300 Việt kiều, many mixed-race, and Baloup’s poignant retelling of it explores some of the shame and sadness of the site, as well as its complex history and ongoing role in the community. Based on the many interviews conducted, Baloup writes:

Some inhabitants seek to preserve their history, others want to forget about it.

The two comic books by Truong stand somewhat apart from the others, serving as important anchors. In a previous review on diaCRITICS, reviewer Nora A. Taylor suggests that, “with these books, Truong has not so much given us history lessons as guided us toward a reflection on the intersections of history and memory.”

Born in 1957, Truong’s books are largely told as eyewitness accounts, girded by his mother’s detailed correspondences and more recent conversations with his late father. Truong’s Vietnamese father was a diplomat and right at the start of the first book, he is called back from Washington DC to serve President Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam. Soon his father becomes directly connected to the inner workings of the South Vietnamese government.

Truong’s was a privileged and transnational childhood, a ‘third culture kid’ long before the term existed. Though Vietnam’s French colonial past is not explicitly explored, it’s a conflict inherent in his own family’s mixed-race identity. His French mother struggles with life in wartime Vietnam. Eventually she is diagnosed with ‘manic depression’ and the polarity of that condition is an echo of the polarity Truong sees all around him.

Growing up in the West, Truong found it a heady time to become a man, fueled by personal discoveries as well as family drama. Meanwhile, the war raged in Vietnam and there were many moments where he felt frustrated by the simplistic understandings of the Western world which sounded like “Orwellian Newspeak” to him. His account of this critical period of history feels particularly valuable for the way it broadens what it means to be part of the diaspora, which is by no means a monolithic group.

Not all Vietnamese are refugees, but all Vietnamese are affected by the war, directly or otherwise.

*

Elsewhere it’s been described that comics captured America’s growing ambivalence about the Vietnam War, so it feels fitting that the Vietnamese diaspora are now using the same form to deliver key counter-narratives. American retellings of the war, after all, are intentionally limited in their scope. As though to redress this, some of the comic books include specific factual accounts of the war, detailing events outside of the narrator’s (and their family’s) direct involvement but clearly based on historical research. Choosing to even undertake such research, it has to be said, is a huge feat in itself.

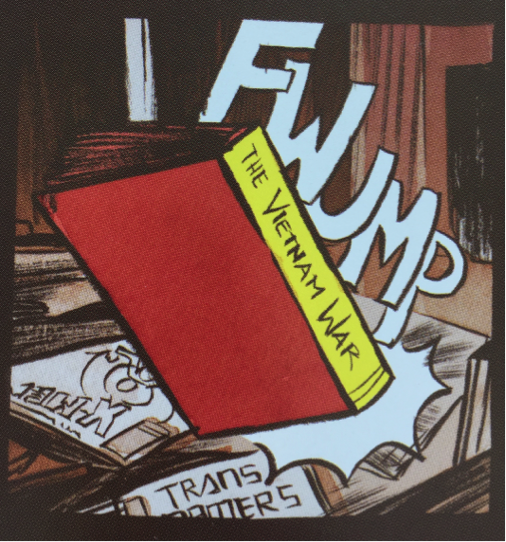

In Vietnamerica there is a recurring and author-less book simply titled The Vietnam War that Tran carries with him from move to move… and never reads. There’s a profound truth in this that I recognised: even when we have access to books (in English), we may struggle to open the covers because it’s simply too close to home.

Another important aspect to note is what Lan Cao wrote in The New York Times series Vietnam ’67. As Cao critiques in ‘Vietnam Wasn’t Just an American War‘, referring to the sprawling documentary series, The Vietnam War, by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick:

From tone to space to treatment, I know that the South Vietnamese is the minor character in the American historical exposition of the Vietnam War.

With the ongoing interest in the war, it’s no surprise that a reckoning is taking place by Việt kiều thinkers, writers, and artists in the United States and elsewhere. We’re tackling histories that have been disavowed, even edited out, and bringing to light the missing and under-told details from our collective experiences. Baloup’s work suggests something similar is also happening in France, re-examining its colonial history in Asia.

When Truong set out on the creative process that would become his two books, he initially thought these would just be memoirs. But soon he understood that he was going to be a spokesperson about the war itself, as he described in an interview:

We South Vietnamese became the walk-on parts of our own war. The Vietnam war has often been told either by gung-ho hawks, or by antiwar intellectuals and activists, and nothing much in between.

In this regard Truong’s account is an important wedge, detailing important aspects of South Vietnam’s wartime history, echoing Cao’s op-ed in The New York Times. It’s a history that has also largely been erased in post-war Vietnam where the war is referred to as “The American War” rather than a civil one. Vietnamese American artist Tiffany Chung describes this problem as “politically driven historical amnesia“, from her time living and working in Vietnam over the past two decades.

Vietnam as a country is something the diaspora feels ambivalent about, “a symbol of something lost”, as Bui writes in her book. After all, the Vietnam of today is one in which the majority of the population was born after the war that triggered the flights of our families. For those of us who decide to return later in our adult lives, it’s a confronting experience. In Tran’s work there is a dizzying double-page spread from his memorable second return to Vietnam. Examining these richly detailed panels, memories of my first trip in 2010 were brought back with full force.

Reviewing all of these books, something which emerged for me is considering that one of the key differences between being a refugee and a migrant is that when you are the latter, you can properly pack your bags. This is a detail Tran explores in a resonant way, when he realizes that his mother doesn’t have any photographs. In Bui’s book, the box of photographs that arrives from Vietnam is a boon. These scenes bring to mind Nathalie Huynh Chau Nguyen’s Memory is Another Country, which has a whole chapter devoted to ‘Lost Photographs’.

The absence of photographs in many of our lives is why comics feel like an act of recovery, with images created from memory, imagination, and reportage—to fill in the gaps.

*

Visiting Vietnam again at the start of this year, I met up with a Vietnamese Canadian friend, Linh Phan, who commented that so many of the incoming Việt kiều she had met over the years were still fixated on The War. Linh said this as someone who had now lived in Vietnam for more than ten years, and the country had become a pulsating place full of memories formed in adulthood. Her secondhand trauma relating to the war had dimmed. When she made the comment I paused before answering; I understood exactly why many Việt kiều are still concerned about the war, yet I found myself agreeing with Linh as well.

On this most recent trip I found that I struggled less with the war, and the burden felt far lighter. Visiting so often in recent years, Vietnam had also begun to change in meaning for me. The other thing I reflected on later was that in the months preceding the trip, I had actually read most of these comics. Together these books had offered me solace, understanding, and space in ways that definitive books—and documentaries—like The Vietnam War simply do not.

CONTRIBUTOR BIO

Sheila Ngoc Pham is a writer, producer and broadcaster based in Sydney, Australia. She’s produced radio documentaries and programs for ABC Radio National including The Lost Cinema of Tan Hiep and Saigon’s Wartime Beat, and her writing has appeared in a wide range of Australian and international publications including The New York Times, Roads and Kingdoms, Womankind and New Philosopher. She is currently a PhD candidate at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation and lectures in public health ethics at Macquarie University.

Sheila Ngoc Pham is a contributing editor to diaCRITICS for stories of and from the Vietnamese Australian diaspora.