diaCRITICS highlights Vietnamese artists of the diaspora.

In this profile of visual artist Phung Huynh, we include an untitled essay by the artist. The essay was originally presented as a public reading at the California African American Museum on March 10, 2018, to accompany the launch of an arts and culture journal, Race/D (curated by Kat Sayarath) that featured artwork by Phung Huynh, and others.

.

.

Tell me the story

Of all these things.

Beginning wherever you wish, tell even us.

~Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

“Take this. Read this. It’s brilliant. It will help you in navigating your art.” This is what my professor in graduate school told me, as he gently handed me a worn copy of Dictée by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. My first reading was a dizzy experience that tried to fit together the many fragments and incomplete allegories about identity, displacement, matriarchs, suffering, and representation. I saw Dictée as broken, as many pieces of glass scattered in a blinding mirage of diamonds and crystals, and if I got too close, if I tried to pick up a piece, I would surely cut myself and ruin the moment with my own blood. When I finished the book and returned it to my professor, he told me to keep it, I may return to it some day.

Many years later, the words and images of Dictée continue to appear and reappear in soft and subtle tones. They gently remind me of my own fragmented autobiography, my dislocation, relocation, and assimilation, giving me a kaleidoscopic lens to see the world, broken yet beautiful. My mother and I were born in Vietnam where my grandparents settled as immigrants from southern China. My father is Cambodian and met my mother in Vietnam, the neighboring country where he arrived on his bicycle, racing across the border to escape genocide. As a family of boatpeople, our promise to resettle in America was preceded by an eight-month residency in a Thai refugee camp.

My earliest memories surrendered to family photographs and family stories. “Oh Phung, you were such an ugly baby. You had this giant forehead, small eyes, and a flat nose,” my cousin would say. Mothers in Southeast Asia were told to pinch their babies’ noses regularly, so that it wouldn’t go flat.

The photograph that was used for my green card, or my permanent alien resident identification card, revealed an image of a little girl self-consciously trying to look pretty. My mother proudly cut my hair at asymmetrical angles and made my red suit and white blouse. My fingernails were painted red but nervously chipped. “Oh Phung, your mouth would be more delicate and less swollen-looking if you didn’t nurse for so long, and if you didn’t drink from the bottle until you were six,” my mother would tell me.

As I grew and as my hair grew, my grandmother would take my black strands in the tightest grip to make two perfect braids. It hurt, and I would whimper, but ah-mah would say, “If you want to be pretty, it has to hurt.” I would sit on the ground in front of ah-mah with the back of my head occasionally knocking against her knees, and she would tell me stories about girls who had their feet bound in China. They would cry, refuse to eat, crippled by excruciating pain to have a pair of feet that would eventually look like a couple of small, three-inch golden lilies. “Your great-grandmother had her feet bound, you know. She said some girls would die because it hurt so much. But no man would want a wife with big feet.” Later as an adult, I would read about these girls, these women with bound feet, and I saw photographs and paintings of their tiny feet, tiny shoes, small eyes, small mouths, and small breasts.

These women occupied a flat, ancient, mythical space. I looked at them, but I did not want to look like them. My idea of what is pretty was already shaped by Barbie dolls with golden hair, big sapphire eyes, large plastic breasts, and small pointy noses. This image of pretty repeated itself in fashion magazines, television commercials, cinema, and every corner of popular culture.

As prepubescent girls, my sister and I would often spend our summers in Miami visiting our cousins, aunties, and uncles. One summer, our two eldest cousins, who were like our big sisters, were away. They had gone to Los Angeles where our auntie had arranged for their nose jobs. Every summer, we would return home to reprimanding matriarchs, “How did you get so dark?”

Mom would also say, “Phung, if you want to, when you turn sixteen, you could have surgery to have your eyes widened and finally get those double eyelids.” Luckily for me, after many hopeless attempts with tape and toothpicks to train the skin to dutifully crease, my lids eventually doubled on their own without surgery.

And now, as a woman with two young sons, my body has embraced a postpartum frame I have learned to accept. “You know, che,” my younger sister would say, “Dad says we can have our boobs done, and Mom says we should do it during the summer so that we can have enough time to recover before we go back to teach in the fall.”

But, who needs surgery now when there are skin-lightening creams, nose rollers, colored contacts, hair dyes, and bleaches for a variety of hues? These products and devices shift and mold our faces and our bodies in ways that make us think we are pretty but erase who we are. The contemporary Asian female body has become the place to carve notions of beauty, of cultural perception, the remapping of identity, and the obscurity of racial identity. I did return to Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, to her Dictée, because it has also returned to me in delicately haunting leaves of memories, images, poems, and cautionary tales.

~~~

From A Far

What nationality

or what kindred and relation

what blood relation

what blood ties of blood

what ancestry

what race generation

what house clan tribe stock strain

what lineage extraction

what breed sect gender denomination caste

what stray ejection misplaced

Tertium Quid neither one thing nor the other

Tombe des nues de naturalized

what transplant to dispel upon

—Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

~~~

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Phung Huynh is a Los Angeles-based artist whose practice is primarily in drawing and painting. Her work investigates notions of cultural identity from a kaleidoscopic perspective, a continual shift of idiosyncratic translations. The contemporary American landscape is where she explores how “outside” cultural ideas are imported, disassembled, and then reconstructed. In an overwhelmingly diverse metropolis such as Los Angeles, images flood our social lens through mass reproduction and social media, taking on multiple [mis]interpretations. Such reflections have guided Huynh in re-stitching traditional Chinese iconography within the loosely woven fabric of American popular culture. There is a purposeful “Chinatown” aesthetic in Huynh’s paintings, alluding to kitsch souvenirs that tourists purchase and commodifications of eastern icons into tchotchkes. Dismantling cultural authenticity, she paints images of Chinese cherubs, lotus, carp and silk textile designs with a “pop” veneer that collide in a complicated composition of delight and horror to challenge the viewer with a western-leaning perspective, as well as the viewer with a nonwestern-leaning perspective.

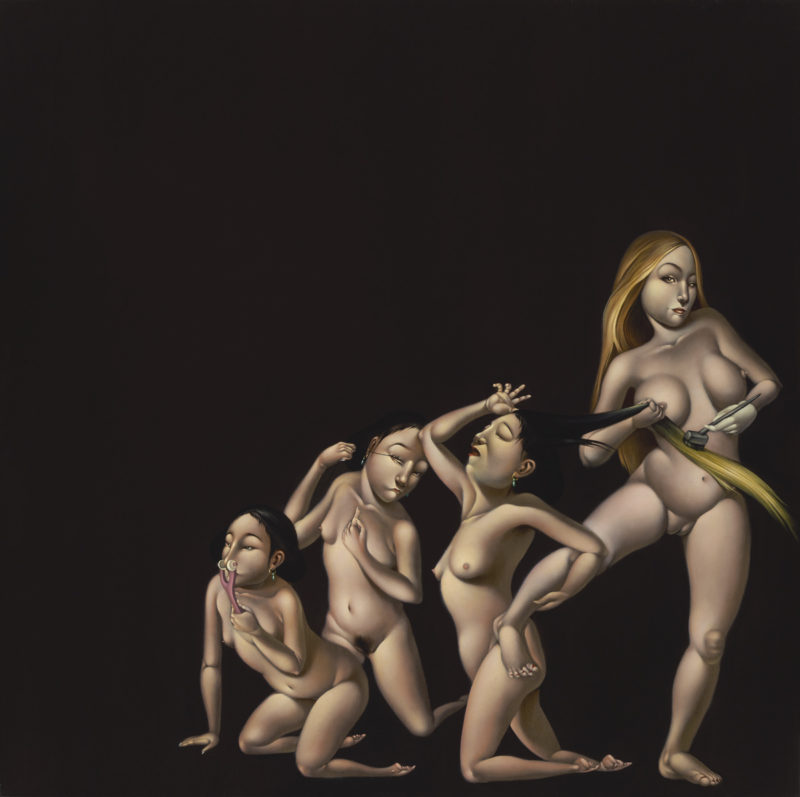

Huynh’s most current work continues to probe the questions of cultural perception and cultural authenticity through images of the Asian female body vis-à-vis plastic surgery. She references Chinese feet-binding as one of the earliest forms of cosmetic surgery to contrast the antiquated canon of Asian feminine beauty (small feet, small eyes, a broad forehead, and small breasts) with the current trends of body image influenced by western canons that call for larger eyes, a delicate forehead, a taller nose, and larger breasts. Huynh is interested in how contemporary plastic surgery on Asian women have not only obscured racial identity, but how it has also amplified the exoticism and Orientalist eroticism of Asian women. Therefore, the awkward synthesis of her projects of traditional and non-traditional, of east and west, unravel ideas of cultural representations and stereotypes to challenge how we consume and interpret ethnographic signifiers.

Learn more about Phung Huynh’s art and process in her interview with VoyageLA.

Artist website: www.phunghuynh.com

Follow on FB: Phung Huynh, IG: @phungxion

–

All art images by Phung Huynh. Used with permission from the artist.