When I first saw the AmenTV video clip titled “Trao giải cuộc thi ảnh tàn phá Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng,” or “Awards presentation for winning photos of the destruction of Loc Hung Garden contest,” posted to YouTube on Feb. 4, 2019, I couldn’t help feeling puzzled, a bit contemptuous. What was there to celebrate over such heart-wrenching demolitions of more than 100 homes by local authorities in a land-grabbing scheme that sent hundreds into sudden homelessness just days before the most important holiday of Tết?

But once I’d watched the 41-minute clip, I understood. And was genuinely moved. The photo contest preserves proof of the Vietnamese communist government’s brutality and manipulation regarding “Land Use Rights” for citizens in Vietnam.

“The idea of organizing this photo competition came from a newly-assigned adviser priest of Dòng Chúa Cứu Thế [The Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer] of Việt Nam, in a plan to preserve the images as evidence that this society is being governed by a communist government that is not completely for the people and the country,” the Reverend Father Antôn Lê Ngọc Thanh of DCCT said at the beginning of the awards presentation, as he and four of the six winners awaited Giao Thừa, or Tet Eve, in a small room simply decorated with a framed image of Our Mother of Perpetual Help and a rose plant made out of pieces salvaged from the piles of aluminum roofing of Lộc Hưng’s demolished homes.

“Their actions horrified the people considering it’s almost Tết. Like Father Trương Hoàng Vũ has expressed, ‘If someone has never experienced what war’s like, that person needs only to come to Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng to see,’” Father Thanh said. “In this sorrowful, disastrous situation we have come together for solidarity via these images of the war-like destruction you’ve taken between January 4 and 8 and the following days.”

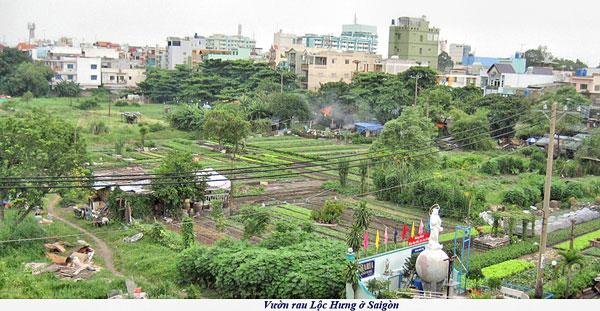

On two days, Jan. 4 and 8, 2019, hundreds of security police personnel from Tân Bình District of Ho Chi Minh City surrounded the Lộc Hưng Garden as heavy equipment moved in and demolished more than 100 homes of the families, many of whom had lived and cultivated the 11.8-acre area of land since their immigration there from the north in 1954, following the division of the country under the Geneva Accords that ended the colonial war.

The forced land confiscation took place suddenly and without proper legal processes. Residents learned of the takeover only via word-of-mouth and a district announcement posted on a neighborhood wall. And there were no plans to relocate the displaced.

The local authority justified its action by claiming some of the houses were constructed illegally on agricultural land. The entire area was leveled by Jan. 8, then almost immediately cleared of all debris. A billboard with colorfully rendered plans for new site projects (including a public high school and some highrises) was soon erected on the property, which Lộc Hưng residents saw for the first time.

Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng: Rising from a garbage-strewn swamp

This land, a swampy area, originally belonged to the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (French: Société des Missions étrangères de Paris), a Roman Catholic missionary organization of secular priests and lay persons dedicated to missionary work in foreign lands. The colonial French government received permission from the organization to set up an antenna system on the 4.8 hectares, or 11.8 acres, of property.

In 1955, Father Đinh Công Trình, representing the parish of Lộc Hưng, applied to borrow the land and received an agreement from the overseeing French unit for parishioners to come in during daytime to grow vegetables on empty lots around antenna posts. When the French withdrew from Vietnam, the Society relinquished its right to the land over to the parishioners, as first growers. Under the former South Vietnamese regime, the area’s air space was used to transmit signals for the Chí Hoà Transmitter complex.

Starting April 1977 following the communist takeover of South Vietnam, the area became, like all other private properties, “the people’s property managed by the government” after Lộc Hưng residents volunteered to register as such, and continued to pay taxes for which they have related receipts to prove. As early as 1988 local authorities began to draw plans for the Lộc Hưng area, but never shared them with the residents. In the following decades the communist government began work toward a property law, which was finalized and promulgated in 2014, officially proclaiming all properties belonging to the people are managed by the government. Private property ownership is not recognized, and citizens are allowed ownership of a right to use the land. This right is called the Land Use Right, or LUR.

For 20 years, Lộc Hưng residents have applied unsuccessfully for such LUR. When pressed, local authorities told them there were no plans to develop the area, that every agency was fully aware of the fact that residents had been cultivating it for decades, and that there was no reason to be concerned. Lộc Hưng representatives even went to Hà Nội to appeal, but no agency accepted their complaint for fear of responsibility.

Finally, on Jan. 4, the Tân Bình authority sent heavy equipment in, surrounded by hundreds of security police, to knock down the houses and level vegetable beds. No legal, usually lengthy, procedures took place. Disbelieving, dazed, and perhaps still hopeful that their voices would be heard and problems solved, many residents lingered and spent the next four nights amidst the broken structures, only to be once again caught off guard when in the wee hours of Jan. 8 the demolishing army returned to complete the destruction.

Rising from the ashes: Photo contest of Lộc Hưng demolition

None of the photo contest winners thought they were going to Lộc Hưng to record the destruction for posterity. Some didn’t even have a camera-equipped phone and had to borrow it from someone else. All photos were apparently taken clandestinely by mobile phones.

Spurred by word-of-mouth news and/or social media, they rushed to the scene to see what was going on (since none of the hundreds of state-controlled media outlets were truthfully informing the populace on the situation). They came to offer help to friends living there. Or they themselves were residents of Lộc Hưng, stealing a few shots while running away from demolition excavators furiously at work.

Screenshot, AmenTV, YouTube.

Anna Trang does not live at Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng but has a friend residing there. When she heard of the second demolition wave on Jan. 8, she rushed over to see if she could help her friend move some of her belongings. Her photo, titled “Compassion,” shows a young man pushing a wheelbarrow with a cage in which sat two frightened-looking dogs and a cat.

“I asked him where did he push them to, he said my house has been destroyed, one of his pet dogs was stolen, he was taking these to hopefully find someone who would be able to take care of them,” Trang said. “I was thinking to myself God gave this boy the ability to feel for the animals that can’t take care of themselves. He did not know where he’s going to stay but he’s more concerned about the animals.”

The photo “Following closely ‘hostilities’ at VRLH,” was so named out of its owner’s apparently still-raw memories of the Sino-Vietnam War in 1979, the destruction of which Trần Bang had witnessed in early 1982 as a soldier. In this photo, a photographer snaps a photo of the devastation from the back of a scooter driven by his friend amidst the rubble.

“The fact that the authorities destroyed Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng right at the time Tết was approaching brought me back to the Tết of 1982 around early March when I was transferred from Division 356 to Division 345 to a station in Lào Cai after the Chinese leveled the town,” Bang said. “No structures were left standing, every electrical post was felled, electricity, water, bridges, roads all were destroyed. The demolition was horrific, clean, complete so that no human being could live there.”

“When I arrived at Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng on the 5th, I witnessed similar brutality,” Bang continued. “I was terribly indignant, I raised my concern and wrote about it. The following two days were quiet. I thought the government had stepped back because of strong reactions from all corners. But on the 7th again there were some signals, then on the 8th again blockade, then more destruction. I arrived on the 9th and saw the demolition was more ferocious than the 4th, meaning much cleaner.”

“It annihilates livelihood, obliterates any hope of returning to rebuild. That’s what angers me. … A citizen’s right is the right to housing. Why some Vietnamese drifted to Thailand or Cambodia, the authorities there had to build refugee camps to shelter them? Meanwhile, the government here came and destroyed the houses of those who have lived here for decades?”

Screenshot, AmenTV, YouTube.

Lan Chi resided at Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng. She is the “her” in the photo “That’s her” in which an undercover security agent points toward her as she is filming the devastation. Lan Chi had spun around, aiming her mobile phone at him just before disappearing into the chaos and confusion. Lan Chi was not present at the videotaped awards presentation, but gave a brief interview to an AmenTV reporter about the circumstances in which she took the photo.

“It was on the 8th at around 5 am when we were awakened by loud whistles and commotion outside,” Lan Chi recalled. “I and Trang [either a sister or friend] were saying there must be lots of people blocking outside and it’ll be impossible to get out. We didn’t know what to do but pray. Right then a friend of Trang arrived, telling us to get what’s most necessary to bring with us. We tried to gather our most needed belongings and get out. It’s about 7:20 am when we left the house and found green and yellow uniformed agents blocking everywhere we turned.”

“When we arrived at the entrance of an alley we saw a huge crowd of security police. I told Trang’s friend I thought we had to do something so others could see this scene, otherwise no one would know about this,” Lan Chi continued. “When I suggested that he handed me his mobile phone, and I started to film. While I was doing it a security agent saw me and pointed at me and I got him and that’s how I luckily got the photo with part of his finger pointing at me [no one was allowed to film or take pictures, if caught her phone could be confiscated or broken, explained the interviewer]. It’s Christ’s will in arranging for us to have snapped the image right before he shouted ‘That’s her.’”

Screenshot, AmenTV, YouTube.

Bửu Châu went to Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng to be with the victims and share in their disastrous situation, he said. His photo depicts a little girl sobbing into the front of her blouse that she has pulled over her face; it is titled “Mama! Should I come in or stay in the garden?”

Born after 1975, Bửu Châu had heard often about “chạy giặc,” or escaping the advancing enemy amidst utter confusion, a term which described the fall of Saigon as people frantically searched for a way out of the country before the communist takeover. He said witnessing the events at Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng on Jan. 8th made him realize the meaning of “chạy giặc.”

“I was horrified as I saw people trying to carry heavy bags of rice, others pushing wheelbarrows piled high with their belongings without knowing where to go,” Bửu Châu said.

He spoke of seeing security police stationed at every corner. He didn’t dare to take pictures of them for fear of losing his phone or being arrested. Finally, he got to a rather hidden area where he saw the little girl crying while her mother ran back and forth, not knowing what to take with her before a demolition excavator arrived to level their house.

Screenshot, AmenTV, YouTube.

Like Bửu Châu, Tùng Nguyễn, who took the photo “Today Lộc Hưng – 68 Tết Offensive?”, was speechless when he saw the devastated area the day after the first wave of demolition.

“I do not know what to say. When I arrived at Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng and saw the destruction, I told myself to take as many pictures as I could to show how badly this government treated their people,” Bửu Châu said. “I wanted to, within my abilities, preserve these images so the more people get to see them the better.”

Screenshot, AmenTV, YouTube.

Father Trương Hoàng Vũ’s photo, depicting a pair of prosthetic legs and a crutch leaning against the remnants of a temple wall, titled “Run! Didn’t even have time to gather one’s legs,” landed First Place in the Dòng Chúa Cứu Thế photography contest documenting the destruction of VRLH.

Although he works in the media, Father Vũ said he went to Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng not to report about the incident but to check on a shelter for wounded veterans he had helped to set up and manage. However, he was touched by the sight of the abandoned legs amidst the debris, and couldn’t help wondering about their owner’s whereabouts.

“I came to see about the shelter and its residents when I heard of the demolition and its residents arrested and brought elsewhere,” he said. “We had built the house for them thanks to monetary contributions from many good-hearted people, including many elderly men and women overseas who shared with us their meager savings. It wrecks my heart seeing the house razed. Why the government could be that cruel?”

Father Vũ surveyed the destruction at the shelter and its surroundings. A half-cooked pot of rice, a hearing aid here and there. His gaze paused at the prosthetic legs under the rubble. He picked them up and rearranged them on the broken wall of the Temple of St. Joseph, not sure what to do with them.

“It pained me profoundly seeing these abandoned legs. Then it came to my mind I must take pictures of them to show and tell the world that this government has created this war-like zone,” Father Vũ said.

There were a total of 23 photos sent in for the contest and six were selected for the awards. There was no 2nd place. The photos were rated based on four criteria: first, the photograph creates a strong impression, graded at 4/10; second, it has beauty, 2/10; third, it tells of the photographer’s courage, 2/10; and finally, it carries a lasting value, 2/10. Each winner received a certificate of appreciation and a small sum of money. The contest organizers claimed no copyright but requested a credit be given to the photographers and the contest.

“We will prolong the pains of the Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng experience via artistic activities as long as the government refuses to be fair,” Father Thanh said. “We have nothing with which to fight for our rights but art. We’ll use art to demand justice for our people. Cruelty can’t win over hope. My friends, believe me, we shall be the witness of that.”

Land issues in Viet Nam

The Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng incident is but one of several such land grabs that have occurred in Viet Nam in the name of “building for development.” The cause of the problem resides in the country’s law.

As mentioned above, Viet Nam does not allow private ownership of land. Citizens are issued a certificate of Land Use Right for the use of their very own property. The land belongs to the entire populace and is managed by the government.

“When the law says ‘the land belongs to the people,’ that means the government can take back the land of anybody, at any moment. And that’s a very dangerous thing,” Trịnh Vĩnh Phúc, a Vietnam-based lawyer specializing in human rights defense, told Radio Free Asia in an interview on Jan. 10, two days after the second attack on Vườn Rau Lộc Hưng.

Millions of rural tenants have become vulnerable to local officials’ whims and greed. For vaguely-defined “public interest” reasons, the authorities can reclaim land from anyone at any time, which has led to widespread local corruption, according to several Việt Nam observers. Should victims resist, security police or even armed soldiers are mobilized to surround affected areas. Deadly clashes have occurred.

There’s a Vietnamese term for these land-grab victims: “dân oan,” or victims of glaring injustice. And their rank is growing.

Pushed off their land, farmers and fishermen have lost their livelihood while their lands are leased to developers and investors for so-called economic development. Sometimes a development project has been abandoned for whatever reasons and the land sits idle, yet its former tenants still cannot move back to farm since the land deal has been done.

Protests have erupted everywhere. Some dân oan have even resorted to violence against the violence thrust upon them. Many have been arrested, tried, and imprisoned. Unable to take it anymore, a few dân oan have committed suicide, as happened last July when a man named Bùi Hữu Tuân doused himself with gasoline and self-immolated in front the Government Investigation Agency at No. 1 Ngô Thì Nhậm St., Hà Nội.

A late-blooming economy in the region, Viet Nam has become a dumping ground for heavily-polluting factories that no other countries want. The story of the massive fish death lining some 200 km, or 124 miles, of the central Vietnam coast in 2016 by the heavily guarded, foreign-owned Formosa Ha Tinh Steel, is still vivid, unresolved as many young fishermen had to go overseas to look for work to support their families. Meanwhile, Vietnamese rivers are dying thanks to those factories.

Dotting the country’s pristine coastline are luxurious resorts, highrises only those with money can afford. Developments for tourism have also flourished. When I traveled by bus along the coast between Nha Trang and Mũi Né in May last year, I saw and photographed many such developments. Many tourists are impressed with the so-called economic developments in Viet Nam. They exist at the expense of the dân oan, as well as of the environment.

“Everywhere in Viet Nam, the more development projects come into existence, hundreds, thousands and tens of thousands of people have lost their land and become dân oan,” Lawyer Phúc said. “Viet Nam’s current land law has created corruption, special interests, sorrows, and displaced persons. It is turning this country into a superpower of dân oan.”

–

A Vietnamese version of this article was initially published by Việt Tân and Da Màu.

CONTRIBUTOR BIO

Trùng Dương, born Nguyễn Thị Thái, 1944 in Sơn Tây, North Vietnam. Emigrated to and grew up in South Vietnam from 1954. Former publisher-editor of the Daily Sóng Thần (Sài Gòn, 1971-75), she’s authored several short and long fictions, essays, illustrations, and a three-act play, My Sons Are Home (1978). A political refugee in the United States since 1975, she graduated from the State University of California, Sacramento with a BA in government-journalism and an MA in international affairs. A 1990-91 Fulbright Fellow in Hongkong, she studied China’s Special Ecionomic Zones. She reported for The Mountain Democrat, Placerville, Calif., 1991-93; then worked as copy editor then chief librarian at The Record, Stockton, Calif. until retiring in 2006. She now lives in Northern California.

Trùng Dương, born Nguyễn Thị Thái, 1944 in Sơn Tây, North Vietnam. Emigrated to and grew up in South Vietnam from 1954. Former publisher-editor of the Daily Sóng Thần (Sài Gòn, 1971-75), she’s authored several short and long fictions, essays, illustrations, and a three-act play, My Sons Are Home (1978). A political refugee in the United States since 1975, she graduated from the State University of California, Sacramento with a BA in government-journalism and an MA in international affairs. A 1990-91 Fulbright Fellow in Hongkong, she studied China’s Special Ecionomic Zones. She reported for The Mountain Democrat, Placerville, Calif., 1991-93; then worked as copy editor then chief librarian at The Record, Stockton, Calif. until retiring in 2006. She now lives in Northern California.