I understand and live in the diaspora differently than my parents. But, through my parents’ repeated retellings of their stories, with the same tones, rhythms, inflections, and unreconcilable non-endings, I realized that beyond being a ubiquitous source for survival, water, or nước, was also personally symbolic for my parents.

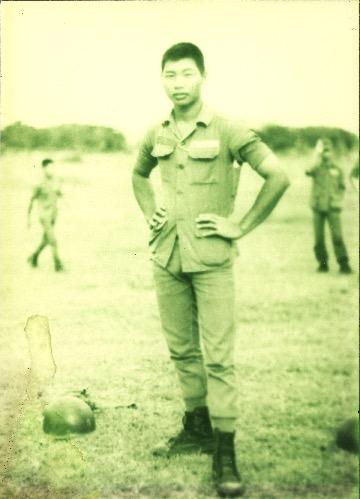

Yến Lê Espiritu references the song, “Biển Nhớ” (“The Sea Remembers”) in chapter three of her book, Body Counts, noting that the “allusion to water in the song title is significant because in the Vietnamese language, ‘the word for water and the word for a nation, a country, and a homeland are one and the same: nước’” (65, original emphasis). Like the choruses of several songs being repeated, stories that I’ve repeatedly listened to included how my father and unknown, distant relatives fought in the air, in the vastness of the sea, and on land to serve and to protect the country’s shores. Like motions of waves, a moving song that at times reminds me of my father is “Biển Mặn” (“Salty Sea,” composed by Trần Thiện Thanh; stage name: Nhật Trường, 1942-2005):

“Trong bao lần quân hành, tôi qua vùng khô cặn

Mồ hôi thành biển mặn trên môi.”

//

“Marching in the dry regions

The sweat tastes like the salty sea on my lips.”

Perhaps I’m romanticizing those memories that don’t belong to me.

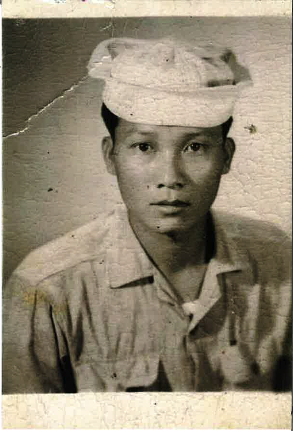

The back of the Polaroid was documented, with my father’s familiar, unique calligraphic handwriting: Subic Bay – May 15, 1975. Recently, my mother’s eyes misted over the memories as the picture shows a haunting image of a fractured family of – then – three, temporarily residing at the refugee camps in the Philippines, where they became exilic boat people, another unintended yet inevitable allusion to the wavering imageries of nước.

On that boat, dead, decomposing bodies were thrown off for the living to survive.

My parents have always inhabited the obscurity of the water’s waves, even after they left them behind on shores of fading memories, with some disappearing and one remaining.

Sometimes only the objects washed back ashore maintain those past memories, dried up.

Author Bio

Kathy Nguyen is a doctoral candidate in Multicultural Women’s and Gender Studies at Texas Woman’s University. Her parents became refugees after the fall of Saigon in 1975 and permanently settled in Arkansas after temporarily being rehomed in Fort Chaffee. Kathy attended the University of Arkansas where she received both her bachelors and MSW. Broadly, she is interested in Asian diasporic narratives and the memories associated with the loss of home and disappearance of citizenships, often examining them through literature and music. While not musically gifted, she has fond memories of listening through her parents’ cassette tapes and watching musical variety shows on VHS and DVD with them. Interestingly, she learned to read and write Vietnamese, though not very well, by watching Vietnamese karaoke DVDs, much to her parents’ bemusement.

Kathy Nguyen is a doctoral candidate in Multicultural Women’s and Gender Studies at Texas Woman’s University. Her parents became refugees after the fall of Saigon in 1975 and permanently settled in Arkansas after temporarily being rehomed in Fort Chaffee. Kathy attended the University of Arkansas where she received both her bachelors and MSW. Broadly, she is interested in Asian diasporic narratives and the memories associated with the loss of home and disappearance of citizenships, often examining them through literature and music. While not musically gifted, she has fond memories of listening through her parents’ cassette tapes and watching musical variety shows on VHS and DVD with them. Interestingly, she learned to read and write Vietnamese, though not very well, by watching Vietnamese karaoke DVDs, much to her parents’ bemusement.