diaCRITICS highlights Vietnamese and Southeast Asian artists and writers of the diaspora. In this Part 2 of our two-part artist profile of Cambodian-born artist Anida Yoeu Ali, she talks with diaCRITICS editor Dao Strom about what it means to work in the hybrid, transnational, diasporic space. Read about Ali’s project, The Buddhist Bug, in Part 1 of our profile.

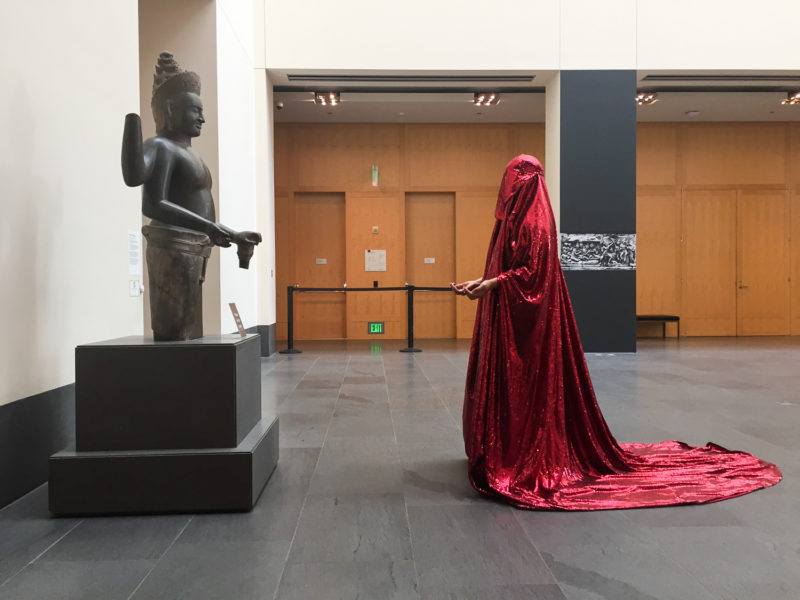

I met Anida Yoeu Ali for the first time in San Francisco in 2016, at a mutual friend and colleague’s house. Photographs from both her Buddhist Bug and Red Chador series were part of a group exhibit, Love In the Time of War, at SF Camerawork (being presented in partnership with DVAN). In connection to the exhibit, I soon learned, Ali was also going to perform her Red Chador project impromptu–guerilla-style–on the streets in front of the SF City Hall and inside the Asian Art Museum. Not quite knowing what to expect and having time on my hands, I took a bus downtown and waited on the art museum steps looking out for the Red Chador to make her appearance. Soon, I saw her approach, a billowing red figure, with the ripples of her skirts flowing, pooling, in her wake.

I met Anida Yoeu Ali for the first time in San Francisco in 2016, at a mutual friend and colleague’s house. Photographs from both her Buddhist Bug and Red Chador series were part of a group exhibit, Love In the Time of War, at SF Camerawork (being presented in partnership with DVAN). In connection to the exhibit, I soon learned, Ali was also going to perform her Red Chador project impromptu–guerilla-style–on the streets in front of the SF City Hall and inside the Asian Art Museum. Not quite knowing what to expect and having time on my hands, I took a bus downtown and waited on the art museum steps looking out for the Red Chador to make her appearance. Soon, I saw her approach, a billowing red figure, with the ripples of her skirts flowing, pooling, in her wake.

The Red Chador is, in short, a fabulous, red-sequined garment. It is the undeniable opposite of invisible, or discreet, or suppressed, a paradoxical garment in that it states bold presence at the same time it completely veils the face and body of its wearer, the Muslim-Khmer-Cambodian artist inside who is using fabric and inhabitation–embodied performance–to subvert expectations, all the while not speaking as she walks about, turning heads, striking a lone and emboldened figure. I was struck by the sheer color of this performance, the audacity of the sparkling red against the city’s blues and grays, and the enervating sense it created, to see this mythopoetic figure take embodied form in a real, unstaged setting. The performance was fleeting, visual, and one had to follow it in order to see it through – it did not stay in any one spot for long.

There is much more to the story of the Red Chador and Anida’s journey with that character than we have space for here today, but I glimpsed a snippet of her journey that day and learned something about how an artist must carry and protect her creations–the ghosts, incarnations, alter egos that enter and inhabit our ever-shifting diasporic bodies. To be able to imagine anew a mythical, or myth-suggestive, figure, to draw fabrics and shapes out of old cosmologies into the now, to re-fashion them with playfulness and verve (and, in the case of the Red Chador, in decidedly feminine form), all of this certainly resonated with me. I followed her from City Hall into the museum, watching as she chose to commune with some objects and people, and not others. –DS

Empowered in the In-Between: A Q&A with Anida Yoeu Ali

DAO STROM: You describe your art as work that investigates “the artistic, spiritual and political collisions of a hybrid transnational identity”. For our readers who may be predominantly of the Vietnamese American diasporic community (i.e. often identifying with a hybrid identity that considers, perhaps foremost, their place in their western countries), can you speak to how and/or why you have chosen to make your art in a “transnational” context?

ANIDA YOEU ALI: It wasn’t really a choice. My process and journey have taken me into a transnational framework. For most diasporic folks, they may only get one chance to “return” to their parents’ native land or their own “motherland.” And for some, living in diaspora is not by choice but a kind of exile, thus never even affording the opportunities for any kind of return. But for me I have truly lived a kind of “back and forth” experience where that “in-between” space has become a bridge or tunnel (much like the ideas behind The Buddhist Bug series) connecting distances between multiple homes. In other words the “in-between” has been a powerful space for creation, which I have whole-heartedly embraced. Sometimes parts of those hybrid identities are made more visible through certain works, sometimes they are much more subtle but always they are intersectional and always unapologetically me. I am of mixed heritage being Khmer, Malay, Cham and Thai – a reminder of how fluid the borders were before the Vietnam War devastated Southeast Asia. When my parents’ finally took us on our first overseas trip “home” in 1992 it was not to Cambodia but rather Malaysia. I actually never stepped foot in Cambodia until I was 30 years old in 2004 – 25 years after my family fled the Khmer Rouge. When I took residency in Phnom Penh from 2011-2015 that was when my artistic work took on a scale and scope that felt truer to who I wanted to be as an artist. It felt like everything that I had created in America prior were merely sketches and prep work for what would and could only be unleashed once I made the choice to root myself in my ancestral land. I appreciate and honor all of my Asian American movement work especially within spoken word and theater because that body of work gave me the confidence and courage to speak my mind and rage on. My work in America prior to 2011 gave me the fire, the community and the language I needed to keep going no matter what system, circumstances and displaced situation I would experience. I know it is a privilege to be where I am having the ability to work both in Southeast Asia and the US, and for the most part to take my work internationally. I love that I get to make and present work in various corners of the world and am perfectly comfortable doing so. I love that I have multiple places I call home from Chicago to Cambodia and Kuala Lumpur to Tacoma.

DS: Who/where is your community or communities? Who/where is your intended audience(s)?

AYA: I despise this question but since it’s being asked by a non-white person for a non-white audience I’ll go ahead and attempt to answer it. Wait. I still despise this question. Ultimately, I write and make art for myself. Saying this is not selfish nor egotistical because I know that I come with my communities, my family, lineage, ancestry, stories and my own sense of originality and narrative voice. I know my work, stories, perspective, politics, and complex outlook on the world has been missing often erased from mainstream media outlets, gallery walls, museum exhibition spaces, bookshelves, classrooms for so fucking long and I believe it’s our time. So, I make work to survive a world that has rendered me invisible and has even attempted to kill me. It is the only way I can make sense of this world and life I’ve been given. I make my work so Others can see me and that includes white People though they exist in my periphery and never central to my work. I want my work to be felt and shared with Others who have had thoughts of their own erasure, difference, strangeness and marginality. I wear my shifting identities very proudly and I know it comes with great responsibility. I have become my own family’s storyteller and storykeeper so I take those responsibilities very serious because of our near annihilation. But I also know that I don’t have to be literal nor always so serious with my work. I have learned to enjoy my process and actually have some fun with my work over the course of my artistic career. I’m not afraid to have difficult conversations and often force encounters upon the unsuspecting. I’m also not afraid to want to have money and a way to provide for my family, a way to survive a capitalist structure with my soul intact while still desiring “nice” things. I don’t believe in the stereotype of a “starving artist” and feel strongly that has been detrimental to our field. So back to who/where is my audience? My audience is wide ranging and also very specific because I don’t want to always explain and decode things because folks are clueless. It’s the reason why I love working in Southeast Asia – people get it and there are researchers and writers who understand the context and content from which I am working from. In America, it’s different because people here trip up on complexities they can’t grasp especially when your identity is not easy to box up or you create something that has nothing to do with identity! In America, you are beholden to people’s liminal view on representation and so you end up being forced to explain over and over, decode over and over. I don’t think I really answered the question. It’s why I despise the question. There isn’t a good answer and we shouldn’t have to try to define it. My audience is anyone who wants to take a risk with me or maybe I’m just looking for co-conspirators and fellow agitators.

DS: We are aware that the diasporic Vietnamese narrative and experience generally receives more attention than stories of other Southeast Asian diasporic communities–who are, and were, yet no less affected by the legacies of the war in Southeast Asia and its aftermath and consequences. What would you, as a Muslim Khmer Cambodian woman artist, like our readers to know about the challenges and/or triumphs you have encountered through making art – and “agitation” – from the body and perspective you inhabit?

AYA: I think your readers already know this but I would like to highlight this point. Identities are not fixed and should never be essentialized– our identities are dynamic, influx, complex and ever-changing. I have been thinking a lot about the burden of representation that I feel is a strongly American context and dilemma that is rooted out of racial injustices and a constant racialization we cannot escape. It is insidious and can be debilitating and dare I say – obstructive to creativity and imagination. Racial formation in the US context means always being reminded of white Supremacy and the ways in which it violates us every day of our lives. I get re-integration depression each and every time I return here to the US because I have to psychologically and physically prepare for the onslaught of micro-aggressions, reminders of my (de)value, expectation to educate others (especially white liberals) and the layers of sheer violence we are exposed to everyday that is particular to being here in America. Sometimes, we just need to make space for each other and de-centralize the importance of our own American-ness. We should make the conscious choice of leaving America, and leave often. Embracing my diasporic existence means I get to be empowered within that complex “in-between” space.

Artist Bio

Anida Yoeu Ali (b.1974, Cambodia) is an interdisciplinary artist whose works span performance, installation, new media, public encounters, and political agitation. Raised in Chicago and born in Cambodia, she is a woman of mixed heritage with Malay, Cham, Khmer and Thai ancestry. Utilizing an interdisciplinary approach to artmaking, her installation and performance works investigate the artistic, spiritual and political collisions of a hybrid transnational identity. Ali is the winner of the 2014-2015 Sovereign Asian Art Prize for her series The Buddhist Bug, a multidisciplinary and internationally recognized work that investigates displacement and identity through humor, absurdity and performance. No stranger to controversy, in 2018 Ali announced the “death” of the Red Chador, a public intervention series highlighting Islamophobia, after returning to America from Ramallah, Palestine without the luggage containing the one-of-a-kind performance garment. Ali has performed and exhibited at the Haus der Kunst, Palais de Tokyo, Musée d’art Contemporain Lyon, Jogja National Museum, Malay Heritage Centre, Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, The Smithsonian, and Queensland Art Gallery. Her artistic works have been the recipient of grants from the Rockefeller Foundation, Ford Foundation, the National Endowment of the Arts and the Art Matters Foundation. Ali’s pioneering poetry work with the critically acclaimed performance group I Was Born With Two Tongues (1998-2003) is archived with the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program. Currently based in Tacoma, Ali is also the co-founder of Studio Revolt, an independent artist run media lab whose works have agitated the White House, won awards at film festivals, and has redefined what it means to create sans-studio and trans-nomadically. Ali holds an MFA from School of the Art Institute Chicago (2010) and a BFA from University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (1998). Ali currently serves as an Artist-in-Residence at the University of Washington, Bothell where she teaches courses in Interdisciplinary Arts, Global Studies and American & Ethnic Studies. She spends her time traveling and making art between the Asia-Pacific region and the US.

Current & Upcoming Exhibitions by Anida Yoeu Ali

A two-month solo show of The Buddhist Bug: A Creation Mythology just finished at Wei-Ling Contemporary in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. This exhibition contained the entire collection of images, videos and text created for The Buddhist Bug project from 2009-2015, including some images that had never been publicly exhibited. The project began conceptually in 2009 in Chicago and was not fully realized until Ali took residency in Cambodia from 2011-2015. The work has since been exhibited internationally with live performances in Cambodia, Singapore, Lithuania, Japan, France, Taiwan, and now Malaysia.

+

Ali’s work is currently on view at Haus der Kunst in Munich until Sept 29, 2019 as part of Archives in Residence: Southeast Asia Performance Collection Exhibition.

+

Ali and her collaborating partner, Masahiro Sugano, will be artists-in-residence at Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture and Design from Nov 7-17, 2019 in Honolulu. Ali: “This commissioning residency will be the beginning of a long process to rebirth and re-envision The Red Chador performance, the work that was taken from me in Tel Aviv. Our residency begins with a collaborative program with the American Studies Association annual conference.”

+

Group Exhibitions:

“Modest Fashion” at Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, Sept 21, 2019-Feb 9, 2020 (Schiedam, The Netherlands)

“Shaping Geographies: Art | Woman | Southeast Asia”, Nov 23, 2019-Jan 5, 2020, at Gajah Gallery (Singapore)

“Periphery” Biennale Jogja XV, Oct 20-Nov 30, 2019, at Jogja National Museum (Yogyakarta, Indonesia)