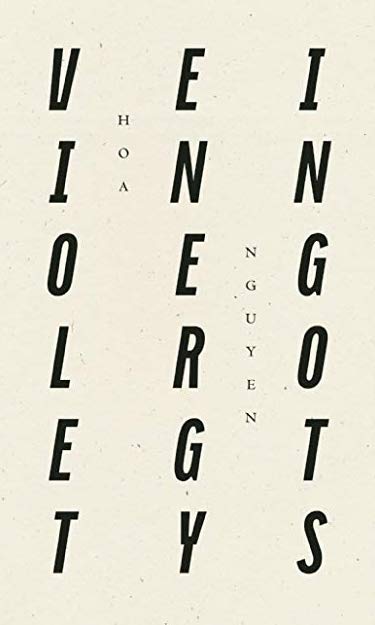

diaCRITICS highlights artists and writers of the Vietnamese and Southeast Asian diaspora. This week, we feature a Q&A with poet Hoa Nguyen, whose latest collection, Violet Energy Ingots (Wave Books; shortlisted for the 2017 Griffin Poetry Prize), was reviewed by our book reviews editor, Eric Nguyen. In 2019 Hoa Nguyen was nominated for the prestigious Neustadt Prize. Here, she talks to editor Dao Strom about the long arc of her poetry journey, poetry ancestors, U.S. versus Canadian diaspora, and the inspiration of her mother.

DAO STROM: I was so happy when I saw the announcement of your nomination for the Neustadt Prize pop up in my social media feeds. I know you and love your work, of course, so that is one reason for my happiness. But it felt even more meaningful in light of how long you’ve been writing, how much you’ve published, and the dearth of recognition – the stunning absence – of Vietnamese women authors from such recognitions in general. You’ve now been nominated for a Griffin Prize and the Neustadt Prize. So, warmest congratulations to you on these well-earned acknowledgments of your contribution to international literature, no less. My first question is simple (and something I ask for myself as well as for our readers): what has kept you going, all of these years of your career, as a woman writer, as a diasporic Vietnamese poet, as a poetic being in this world as it is, as a woman writer who throughout the years has also been a mother raising sons while writing and teaching?

HOA NGUYEN: Thanks, Dao. I don’t really know. My splashy answer might be that it is because I’m a Fire Horse and we’re known for tenacity, dynamism, and our gifts with language. Another answer might be found in a dream I had where I watched a presentation that featured articles of clothing and “esoteric womanly art-secrets”. The presentation was about styling, teaching and being a mother and artist in the world. In the dream I turned to my instructor—life-long friend, Heather MacIntyre, who had just died of breast cancer at the age of 35—and said, “I don’t know what I’m learning!” to which she replied dryly: “That’s the point”. Like the dream I didn’t know what I was doing except that I was doing it—committing my life to poetry so that the shape of my life and my work were the same and it was the subject of my study and practice.

As far as the practical things, I’m from scrappy working class people–I didn’t have access to wealth, ivy league resources, professionalizing connections, etc. I understood that this meant to figure it out and find my way. Besides that, I wanted to be an artist on my own terms and found models in the 80s DIY punk era I grew up around. I held money-jobs not related to poetry or writing and so designed my own course to teach: an independent poetry workshop model that also nourished my practice, thinking, and relationships with fellow writers and still does. Like editing and curating, I kept in it. I was determined to not go away, to never go away. Sometimes I like to say “by sheer will”. My mother would say that I was born under lucky stars, but she also said that you have to make your own luck.

But my commitment has remained rooted in a path that doesn’t seek advancing in some sort of ladder of personal gain; I never considered poetry as career and forever reject the corporate model to poetry. I never approached making art like that; I sought to be more like my dream: to remain a student to poetry and to be myself. I think that’s how I would describe it: to make art as a person in and of the world, to remain alert there as a way of becoming-in-the-world.

DS: Not only are you a diasporic Vietnamese woman writer, but your work is also on the “challenging” and “difficult” side, some would say. You do not directly or narratively address common tropes the average reader might reach for or wish to lean on, nor do you address identity politics and race in as “accessible” terms – perhaps – as may be wanted or expected from Asian American literature. It would seem, rather, that you have resisted, subverted, and defied the conventional expectations, at the same time you’ve unabashedly claimed space for yourself – and your Vietnamese name – in an avant-garde (usually white) tradition of poetry (whether you meant to or not). As I see it, you’ve effectively inhabited the type of ‘write as if you are the majority, unapologetically’ position that Viet Thanh Nguyen has espoused, so popularly, for instance, on Twitter. And you’ve been doing this for years, well over a decade now (long before such things as Twitter storms even existed to help make finding community or context for one’s work as a minority writer maybe a tad bit easier…) Can you speak to tradition or lineage, what it means to you or has meant to you? Who were your literary ancestors, for instance, if you had to say and especially in the beginning? And how did you find them (or they you)? In short: as a Vietnamese writer who started out in poetry at a time when there was little to no context for Vietnamese American poetry, how did you locate yourself or otherwise configure a context for the work you were making?

Language is our species’ most powerful and most fabulous invention–I felt this early and was drawn to poetry’s compression, sonic features, and complexities of meaning and address. As a young reader, I read Dickinson, Millay, and Plath and loved them especially for word-music. I read the English Renaissance poets; I fell in love with Keats. I read the bible from an edition that I convinced my mother to buy from a door-to-door bible salesman; it was enormous with full coloured picture plates, a place to keep your records of kinship, thick pages edged in gold, and a ribbon to mark your place. I was also drawn to folk poetry, songs, ballads, and poems by “Anonymous”. Above all, I recognized that a poem might endure beyond the individual self, that it blurs across time and puts us in contact with others and orders beyond self. And then, when I was maybe eleven, I discovered an anthology of Vietnamese poetry translated into English in my public library called A Thousand Years of Vietnamese Poetry. The first line from the introduction read something like, “The Vietnamese people have always considered themselves poets”, and it unlocked something in me, granting me an essential permission to write poetry. Often I think I write poems toward sound, which is also a primary loss, the loss of my first language, Vietnamese—that that language displacement informs the cadence of sound I seek.

Later, when I moved to San Francisco, I met several established women poets who became mentors and “page mothers” to me. Joanne Kyger helped me understand how I might live poetry outside of official systems, taught me the importance of a magical hearth and of finding what she called “the architecture of my lineage”. Anne Waldman inspired me to create my own context, to launch my own writing school for poetry, and to be a politically animated/activated poet. Gloria Frym, my teacher and mentor at New College, instructed me with her complete devotion to poetry and its study; she taught me how to edit a poetry journal and how to be a deep teacher. She helped me form my poetry lineage via her teachings and her writings. Alice Notley taught me how I might invent measure and use voice; she gave me permission to claim a new language, one that is an embodied female voice. Through her, I came to understand the importance of dreams and learned ways to steal story back from the novel.

Always I’m drawn back to the ancient origins of poetry and song, to where music and language, ritual and magic meet. I remain interested in how language can sing and interact across time and thus circulate as true time—what is referred to by Ryo Yamaguchi in his review of Violet Energy Ingots as “quantum probabilities of resonance and reference”. It continues to be my vision for the poems as they move.

You are now a Vietnamese diasporic poet living in Canada. Previously you lived in Austin, Texas (from 1996-2011). I want to ask about the experience of writing/living as a diasporic person in the U.S. versus Canada. What was this change like for you, as a writer and as a “citizen” of the Vietnamese diaspora? Any notable shifts in either your own perspective, or the reception of your work?

It has enriched my perspectives, readership, and relationships. The poetry community here is strong and established and I have been made welcome, supported, and validated with opportunities and resources. I’ve continued to serve poetry and contribute to community making—that sense of hearth I spoke of earlier—to build a nourishing nexus of connection. I’m a member and organizationally involved in Toronto’s knife fork book, now in its third year, a poetry destination for events, books, and workshops. I mentor at Sister Writes, a creative writing community for women facing housing, employment, financial and other life challenges. I edited the 2017 Best Canadian Poetry In English and am serving as the Canadian judge for the 2020 Griffin International Prize for Poetry. I feel strongly about public service and poetry–that one must as a poet include public service acts to poetry as translator, curator, reviewer, editor, publisher etc. As I write this I am actively trying to fight a “grateful immigrant” storyline, but the truth is I do feel incredibly lucky for all of it. It is also amusing to note that Violet Energy Ingots, my last book and one written in Toronto, contains new references: snow in its varieties, a late winter desire to see a flower.

Less amusing but definitely interesting to note is that the etymological dictionary adds the sense of “free” and also “not alien” to the word “citizen” in the late 14th century. Growing up, my citizenship was often in question even though I was an “American” (as a US citizen and because I was raised there); I consistently experienced the dissonance of being “alien”, as considered a conditional American. Here, I’ve never been told a version of the old “Go back where you came from…” but I’m aware that many Canadians don’t consider me “Canadian” (also accurate, I suppose). And I guess I’ll say it plainly: nation-making on this continent is settler colonialism at work, a work that is predicated on a long history of white dominance, systemic violence, and the oppression of indigenous, black, and brown people. It’s a work that collaborates with and extends global imperial exploitation. Moving to Canada has put these perspectives into sharp view, a clearer view, and this is in large thanks to the indigenous networks of activists and artists here.

Naming and language is central to poetry as it connects across time, peoples, and place. As before I hope to remain a citizen to poetry– by supporting poets and community outlets. I hope to continue to be in service to poetry and rooted to place, while remaining cognizant of the complex histories of place.

My sincere condolences on the passing, this year, of your mother. If you could dedicate one of your poems to her (or lines from any poem), which would that be?

Thanks, Dao. I have poems dedicated to my mother and Ocean Vuong used a line from one to close his novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. The line is:

“The past tense of sing is not singed”

She loved this poem.

I wish I had the chance to share with her how Ocean included it in his novel (which is a letter to his mother) and to show her the clip of his appearance on Seth Myers. She would have been touched and delighted by it all.

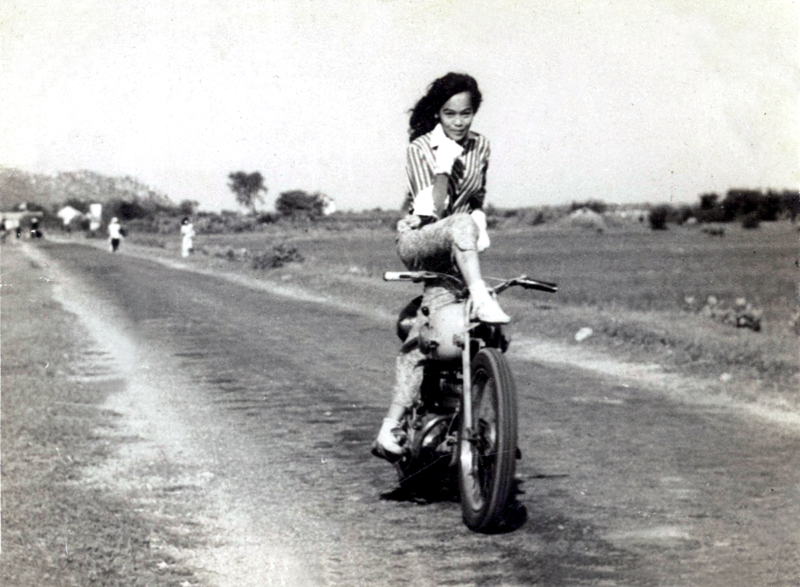

“This is a glorious time, in 1956.

In those days I was a flying motorist artist—

this is the sole memory of my life.

For my friend, to keep as a memory…

The flying motorist artist”

Her Vietnamese name was Nguyễn Anh Diệp (April 21, 1941 – June 9, 2019). When she left Vietnam for North America in 1968, she became Linda Diep Lijewski. She does not leave the photo for the friend but takes it with her.

I’d like to share the whole poem here if I may; it is drawn from a manuscript in progress: a verse meditation on histories, hauntings, origin, and song. This one speaks of my mother’s birth and how she was renamed as a newborn as a way to give her vitality after a difficult breech birth—and more generally on loss, difficulty, and endurance. I should note that her full Vietnamese name was Nguyễn Anh Diệp. When she left Vietnam for North America in 1968, she became Linda Diep Lijewski.

DIỆP BEFORE COMPLETION

Her first name

deemed too delicate

for a failing baby

She was a baby failing

(arrived blue feet first)

Newly named Diệp after the strapping

Chinese butcher

Renamed she recovers!

She says later

“It’s an ugly sounding name”

and thus not popular

I say it wrongly

fake my way

Do we believe in

The Compassionate Protector

sssssssssssssss of Children?

The past tense of sing is not singed

Author Bio

Hoa Nguyen is the author of several books of poetry, including As Long As Trees Last, Red Juice, and Violet Energy Ingots, which was shortlisted for the 2017 Griffin Poetry Prize. She teaches poetics at Ryerson University, for the low residency MFA programs at Miami University and Bard College, and in a long-running, private workshop. www.hoa-nguyen.com

What does ‘the past of sing is not singed’ mean?

Thank you for posting this interview. I am so glad that Hoa Nguyen has found a home in Canada.

Her social and political engagements in Toronto are admirable. I hope she continues to feel supported

and validated there. And her dearth of recognition is over.

Fingers crossed for the Neustadt Prize and other poetic riches.