There are things so large in our lives they haunt us. They blow past memory; they follow us into sleep at night. Genaro Kỳ Lý Smith captures a landscape of such hauntings in The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born, across time and space—from 1963 to 2008, in Vietnam and the United States—breaking generational and cultural barriers. Through death, memories, and dreams, Smith explores our literal and figurative ghosts.

Smith opens this masterful story collection with the bodies of two Vietnamese boys being chopped by a helicopter in “Dallies.” But it isn’t the War that kills them, it’s a horrific accident on an American movie scene resurrecting the War. Lured by the dream of American luxury after immigrating to the United States, the boys’ father is happy to allow his children to play the roles of themselves. But after the accident, memories and movie images poignantly overlap as the father is left with the ghosts of his children haunting a theater screen. While watching, he sees what no one else can: the scene is spliced by a new one with different Vietnamese children. The moment captures the tragedy between Vietnam’s dream of America and America’s dream of the War. By opening with such violence against children, even accidental, Smith sets the stage for the heartbreak that carries the rest of this collection.

Parents, especially, can’t seem to escape being haunted by their children, even if they believe their children have moved on to better lives. In “Nothing To Write Home About” letter-writing becomes a mystical bridge between Vietnam and the United States. Here, Smith introduces Tu Doc, a mail man working at a communist-run post office. Visited by the parents of children who have left Vietnam, Tu Doc is constantly confronted by their demands for answers concerning the well-being of their children. Using a collage of stories from other letters that have come through his hands, he writes letters for them in the voices of their silent children. When the elaborate web of story-letters is discovered, he and the families he wrote for are sent to a re-education camp. The enforced silence at the camp, after writing hundreds of letters for them, is infuriating and poetic. It leaves us to mourn with Tu Duc and the parents whose children can no longer be resurrected.

Being haunted, however, is not reserved for parents alone. For a child named Minh in “The False Flight of Angels,” memories of his parents he never met means he looks for them everywhere. He imagines a heaven by the beach where his mother sings to him and his father feeds him slices of mango. This wish for his parents cannot be extinguished by his adoptive father Uncle Ky, an athlete who prioritizes his idol Pelé (the Brazilian soccer player) over his son. When landmines are discovered during a soccer game, Uncle Ky risks his own life to clear a pathway for Pelé without giving a thought to Minh. In that moment, Minh realizes that no matter how kind people are, he is doomed to be disappointed in his search for familial love. In the end, Minh chooses to be with his birth parents, allowing his body to move and set off the landmine beneath him; he explodes into flight.

The narrator of “The Flag Above Me” can’t break away from the memory of his mother’s death, either. In this story, Smith deftly weaves the heavy and complex subject of the War into the tragedy of losing a mother—and an entire country—to the violence and misunderstandings war necessitates. The story opens with a Communist flag hanging over a liquor store and the narrator insisting he isn’t communist. His community thinks otherwise. The severity of the community’s reactions illustrates the division of both sides, even years after the War ended. As we learn, however, the flag is neither about Communism nor the narrator’s sympathy for it. Instead, the flag is a testament to the memory of his mother’s violent death in the War and the suicide of Minh, a Communist figure who wanted to show the humanity and unity he wished for all people through his death. Thus, the flag becomes a physical manifestation of the ghosts which haunt the narrator, of Minh and his mother, and of the division of war and—ironically—the wish for unity through war. In the end, the community never understands the gesture and the narrator takes drastic measures to make his point.

Smith’s characters move through lives and tragedies without being heard, their wishes drowned out by memory and loss and the noise around them. And so this is the ultimate loss, the thing that haunts us the most, because it’s the ghost of not being heard through the sound of the gun, through the sound of War, through the voices of others. This is the lesson that carries itself throughout The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born. And within each of these stories is heartbreak that is beautifully rendered and profoundly universal, even more so because the characters can’t quite pin down their ghosts or properly mourn them.

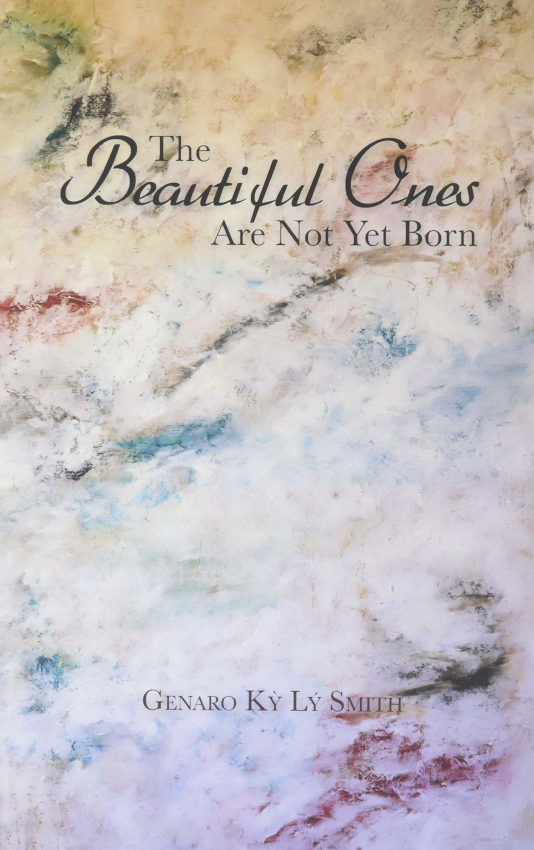

The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born

by Genaro Kỳ Lý Smith

University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, $20.00

Contributor’s Bio

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Tran is a Kundiman fiction fellow, a Lambda fiction fellow, and the recipient of the Jeanne Cordova scholarship for Lambda fellows in 2017. She holds a B.A. from Rollins College, an M.Ed. from the University of California, San Diego, and an MFA in fiction from San Diego State University. Her book reviews, fiction, poetry, and essays have most recently appeared in Brickroad, Vien Dong, Little Saigon, Tayo Literary Magazine, and the forthcoming Foglifter. She is a high school and middle school English teacher, and a mother of two magical little boys. She lives on the shores of Southern California, spending most of her days near the ocean she can’t breathe without.