On living with two names in Vietnam as a mixed-race Viet Kieu American Jew.

As a child, my father took me to synagogue only during the holidays. My mother (born Buddhist) tagged along for as long as she could, but at some point I think she realized that staring at a bunch of Hebrew she couldn’t read wasn’t all that meaningful. Eventually, my father and I stopped going altogether.

On Rosh Hashanah last year, I dressed up for services. My heels clacked along the uneven pavement, still wet from the rain when I dodged motorbike traffic earlier that afternoon. A strange and impractical outfit for Saigon, indeed.

I was doing the High Holidays not only as an act of ritual, but also as a result of a deep yearning for something to feel familiar. Amidst an incredibly abrupt change of scenery—moving across the world to a new country, getting food poisoning during my first week, and most recently, contracting dengue fever. All of this, of course, occurring all at once on my first visit to Vietnam in over a decade.

To be in the presence of Judaism in my mother’s homeland was a coming together of experiences that I didn’t quite have words for.

Approaching the Chabad center, I saw a man with a wide-brimmed hat in front of a sign that read, “Chabad Viet,” and I couldn’t believe my eyes. To see a Rabbi in Vietnam, to hear the lyrical hymns of prayer, to see books with Hebrew text lining the shelves. To be in the presence of Judaism in my mother’s homeland was a coming together of experiences that I didn’t quite have words for.

Passing by the kitchen, I noticed a Vietnamese family preparing the evening meal for dozens of people and I felt a pang in my chest. I couldn’t help thinking about my mother back home as a waitress, my mind unraveling into narratives and metaphors about being both the ‘server’ and the one being served.

A young Vietnamese woman gestured for me to join the others at the dinner table, where I sat next to two white American Jews, the rest of the room comprised of Israelis—all Jewish.

As the Rabbi began a sermon on the importance of this holiday, more of the Vietnamese service staff appeared in the dinner hall, bringing plates of tahini, vegetables, and honey to the tables.

I imagined what this experience would be like had I not been sitting at the table as a guest celebrating the Jewish holiday, and if I instead was spending the evening with that Vietnamese family, helping them bring food out to my fellow Jews—most of whom were likely passing through on vacation, or were part of the influx of Western expats and teachers that were virtually nonexistent ten or twenty years ago.

But tonight, that wasn’t the side of the table I was sitting on.

When one of the workers approached my table to refill our water, I quietly acknowledged her with a “cảm ơn,” and faintly, she smiled back at me, her face revealing a hint of confusion. In the secret exchange between the two of us, I felt both more comfortable, and yet, more lonely too.

The truth is that more often than not the way I feel about my place in the world can be likened to that exact moment in Chabad—a recognition of being in two places, of being two people.

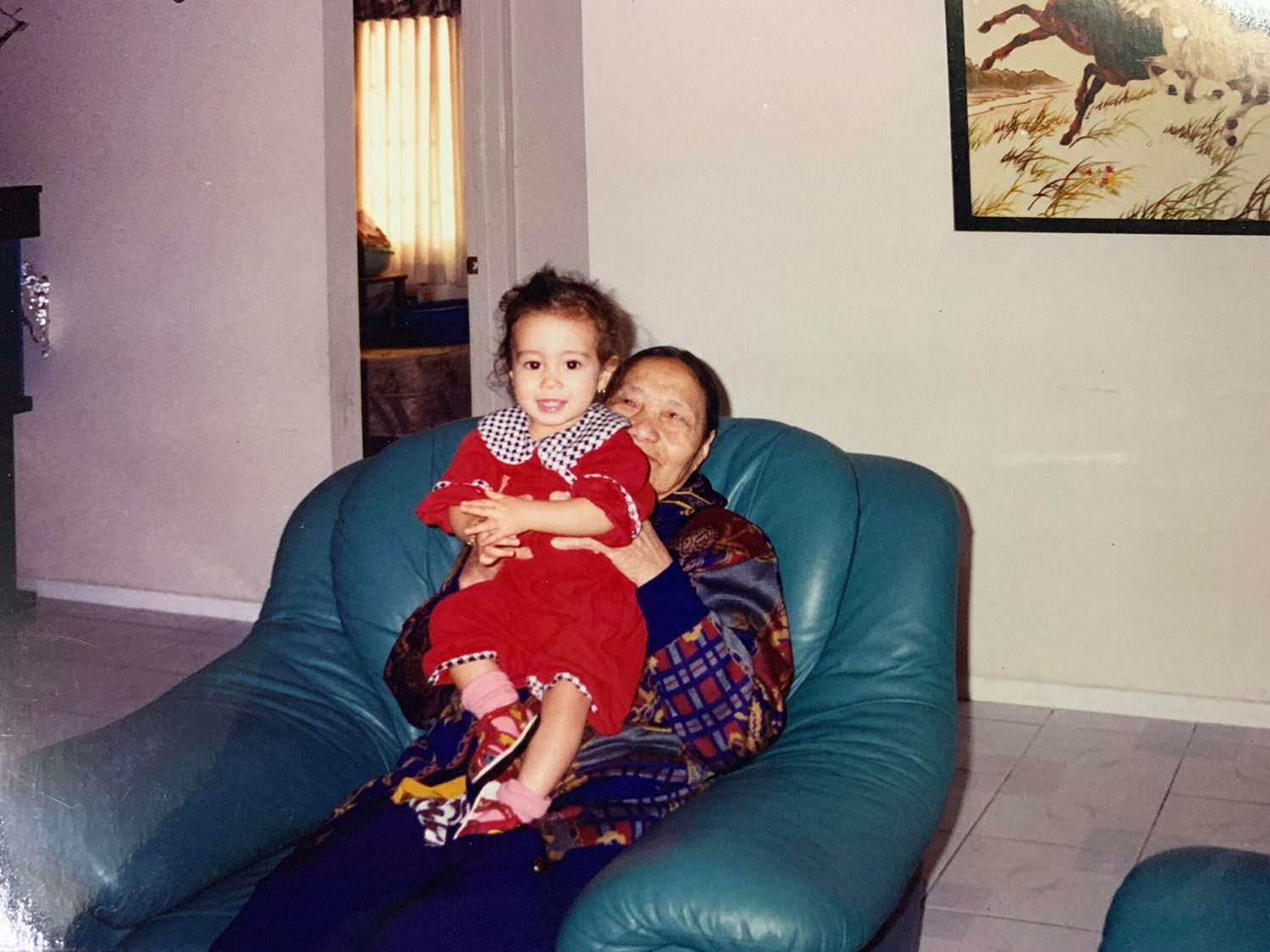

In my new life in Vietnam, it seems I am always choosing which version of me is going to appear. Will it be Gabby Cohen, the foreign American Jewish expat, or will it be Thanh Trúc, the name my bà ngoại gave me, the daughter of Hương Tran, who has now returned to her mother’s home in an effort to reconnect with her roots?

As the “multiple identities” narrative holds, I am often both and neither.

There will never be the right words for the way I feel about my walk along this tightrope of bicultural identity, the uneasiness of being both a minority, while also carrying a passport from arguably one of the most privileged nations in the world.

No matter how much I try to wrap it into a perfectly neat box that can be presented as a nicely polished essay thesis statement, it will always come out at least missing some element of how I really feel, always a little short of politically correct, ignoring or disregarding some important aspect I should have taken into consideration. I only know what I know.

So, here’s what I do know. I may always have to add an addendum to answer the question of “Are you Jewish?” and explain my mother’s Buddhist roots when someone asks. I might require translations for all the Hebrew words, but I can and will always know the essence of shana tova in my bones. I know what it means to feel the sweetness and the blessings of a new year, the seeds of change.

And this knowing, this deep internal knowing, is not unlike the knowledge I have acquired here in Vietnam. Even if my rudimentary Vietnamese and biracial appearance keep me from feeling like I am not fully part of this culture, there are some things that even you cannot undo about yourself.

To be a foreigner here, and yet, still know the sweetness of this country in all of its sticky humidity, wild tenderness, and warmth that shelters my people.

To remember the unforgiving scent but delicious taste of mắm, to smell the aromas of phở and hủ tiếu boiling in the streets, to watch your coffee drop from a phin filter like a light morning rain. To be a foreigner here, and yet, still know the sweetness of this country in all of its sticky humidity, wild tenderness, and warmth that shelters my people.

To understand the concept of surrendering and giving oneself fully to family, to place, to time, through glimpses.

To know that even if I am only participating from a distance, I have arrived home.

Author Bio

Born in Los Angeles, California, Gabrielle Thanh Trúc is a first-generation, mixed-race, Jewish American Việt Kiều. After graduating from the University of Southern California in 2017, she worked in technology and healthcare before relocating to Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), Vietnam, her mother’s homeland. Gabrielle is moved by narratives which interrogate geographical location, and how one’s definition of “home” evolves according to physical space, community, and belonging. She’s written profiles of filmmakers, poets, and other creatives, which have appeared in publications such as FORTH Magazine and USC Cinematic Arts’ In Motion. This is her first published non-fiction essay.

Born in Los Angeles, California, Gabrielle Thanh Trúc is a first-generation, mixed-race, Jewish American Việt Kiều. After graduating from the University of Southern California in 2017, she worked in technology and healthcare before relocating to Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), Vietnam, her mother’s homeland. Gabrielle is moved by narratives which interrogate geographical location, and how one’s definition of “home” evolves according to physical space, community, and belonging. She’s written profiles of filmmakers, poets, and other creatives, which have appeared in publications such as FORTH Magazine and USC Cinematic Arts’ In Motion. This is her first published non-fiction essay.