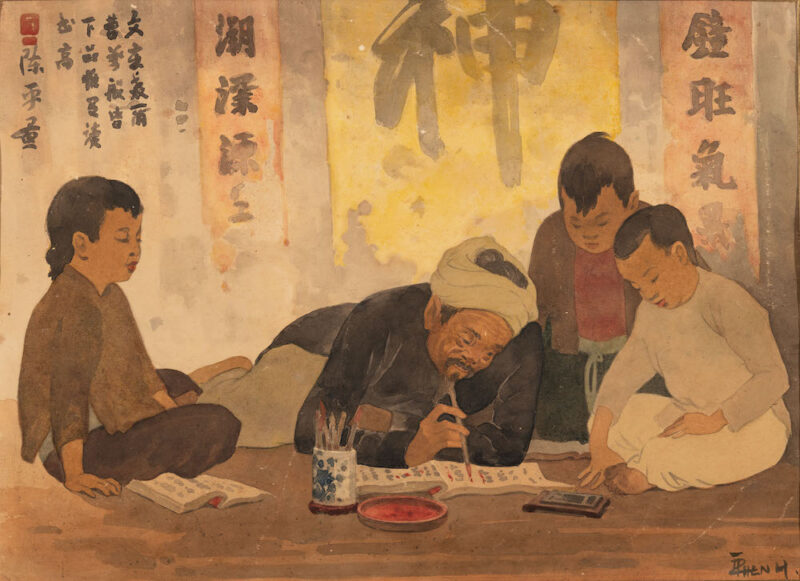

One day in second grade, Mrs. L demonstrated Chinese calligraphy for my class, explaining that it’s an important part of Chinese culture. But I am Chinese too, I wondered – so how come I had no idea what she was talking about?

My family has always self-identified as Chinese, even though they lived in Vietnam for at least two to three generations. Some of my grandparents were born in Vietnam, while others migrated from Southern China. My great-grandparents had arrived in Vietnam after fleeing the Japanese occupation of China. My parents were both born in present-day Ho Chi Minh City, but they were educated in Taiwanese-founded private schools during their early school days; they did not receive a Vietnamese education until after the north and south were united. My dad’s side of the family owned a bustling Chinese restaurant; my mom’s side owned a lumber yard.

Just like Chinatowns across the world, the Chinese community in Saigon at that time was fairly diverse, with residents from Taiwan and Hong Kong as well as southern China. There were sufficient local institutions established by local Chinese to sustain a semi-permeable Chinese community, in which there was no need to shed Chinese identities while selectively adopting local culture. The Vietnamese elements of my family have always been a norm as I was growing up. I was later shocked to discover that a lot of people are unaware that there are Chinese in Vietnam, as well as in other parts of Southeast Asia. Even ethnic Chinese celebrities with Vietnamese-Chinese backgrounds are not generally publicized, while their Western upbringing usually becomes the selling point. Descendants of Chinese-Vietnamese that left Vietnam are now simply Asian American, Asian Canadian, or Asian European.

It is very difficult for me to answer the question, “Are you Chinese?” The answer is long and complicated, and would only make complete sense if the person who asked was somewhat aware of modern Asian history. It is even more complicated because my family speaks Cantonese. Like my parents, I do not have a Vietnamese accent when speaking Cantonese, and am typically mistaken for being from Hong Kong by Chinese-speakers. Yet those who speak Cantonese fluently understand that I do not speak with a Hong Kong accent.

Only those who could afford the fare in gold had the opportunity to escape by sea when the south of Vietnam was “liberated” by the Communists. There were also times when those who were waiting at the beaches were swindled, and the promised ships never appeared. When my family did finally escape, they made the perilous journeys across the ocean separately. My dad’s eldest brother left Vietnam before unification. He was the first one to make it out before the local draft to fight in the Vietnam War. The rest of my family left after the Communist takeover. My dad ended up in Hong Kong with his brothers. They were among the boat people that landed in the British colony in the 1970s.

My mom made the trip with my paternal grandmother and my paternal grandfather’s concubine. Their ocean journey was more perilous. Rumor of pirates on the planned route caused them to take a detour, but they were unable to escape from pirates on the alternate route. My mom recalls that the pirates looked exactly like those portrayed in the movies: big, shirtless men with swords. My grandma smeared dirt on my mom’s face, fearing that the pirates would take the young women. But they only wanted valuables, and were not interested in the women. They destroyed the ship’s steering to prevent them from following, but it was the same as leaving the passengers to die. The current took my mother’s ship up the coast of Singapore. Singapore was not taking in any refugees, and refused to even allow the ship to be fixed. The ship was tugged out to the ocean by a Singaporean government vessel, then the current brought them to an uninhabited island near Indonesia, where the American navy found them and flew them to the US. My mother ended up in Los Angeles, with the sponsorship of a distant relative.

My parents’ siblings ended up in various parts of the world as they made their way out of Vietnam, before settling in Hong Kong, Australia and Canada. After arriving in the States as refugees, my family continued to celebrate Chinese cultural holidays, despite being a few generations removed from the mainland. These family traditions kept our connection to China, in addition to consuming a vibrant Cantonese-speaking entertainment industry out of Hong Kong via cable television. Other than that, there really was nothing else traditional about our Chinese identity.

It was not until much later that I discovered that my self-identified Chineseness was problematic. Not only had I never been to China until adulthood, but my family also no longer has any ties to the mainland. Our supposed ancestral homeland is a village whose name is engraved on my paternal grandfather’s tombstone, and which none of my immediate family has ever visited. If we still have any family left in China, they were either long lost after years of war, or forgotten as we moved further and further away from China.

I visited mainland China for the first time in 2003. Like many ethnic Chinese who live overseas, I learned about China through movies, television dramas, and martial arts fiction. The China I saw and experienced was nothing like what I had imagined, and my time in Shanghai and Beijing that summer made me keenly aware of my own Americanness, which I had never noticed when in the US. Although I later visited other cities in China, in 2009 and 2012, I never traveled to the Sanshui region of Guangzhou, where my family’s ancestral home is.

At a recent conference in Hong Kong, I met a Vietnamese couple from Ho Chi Minh City, who are Sinologists from Vietnam National University. While I do not speak Vietnamese, and they do not speak Cantonese, we found a common language in Mandarin. We talked a lot about Vietnam, a country that I have yet to visit, but feel closely related to. “When we were in Vietnam” is a common phrase in my family, whether they are talking about food, pets, Cantonese opera or television. With American soldiers in Saigon back then, the locals also had access to American television programs, and my parents grew up watching series such as Mission Impossible and Hawaii Five-O. The house my dad grew up in and the family restaurant are supposedly still standing, even though the restaurant has been repurposed.

Before we parted, the husband gifted me some limited editions of Vietnamese currency notes. He encouraged me to let them know when I visit Ho Chi Minh City, and I was surprised when he added, “We are tongxiang.” Tongxiang, literally “same home,” refers to others who are from the same village, the same province, or even the same country. In general, it can be translated as fellows hailing from the same homeland, regardless of the scope. I had never thought of Vietnam as my homeland, just as my family has never considered themselves Vietnamese. But he was right: we are fellow countrymen, and even fellow Saigonese.

Originally published in Los Angeles Review of Books’ China Channel.

Author Bio

Gladys Mac received her PhD from USC. She wrote her dissertation on Jin Yong’s fiction and its visual adaptations. Her research interests range from Asian popular culture to ancient history and everything in between.

Gladys Mac received her PhD from USC. She wrote her dissertation on Jin Yong’s fiction and its visual adaptations. Her research interests range from Asian popular culture to ancient history and everything in between.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing, donating, following us on Instagram or Twitter, and sharing this post to your social networks. You can also join the conversation by leaving a comment!