Nail salons can be found in small towns and big cities across the US and have long been associated with Asian American labor. By exploring the rise of Vietnamese-owned nail salons, filmmaker Adele Pham delves into a chapter of history of Vietnamese arrival in the US and how they made a home here. Nailed It is an origin story of the rise of Vietnamese manicurists in what has grown to a multi-billion dollar industry. We spoke with Adele about the process of making the film, how it’s important to record the history of the women and men in an industry that’s not often treated with respect, and the balance between making a documentary that “sparks joy” while still sticking to the facts.

Nailed It will air on PBS on Tuesday, May 26 at 9 PM.

World Channel will host a screening and Q&A with Adele Pham, on Tuesday, May 26, 2020 at 7 PM. Register here to join.

If you miss the live broadcast, you can stream Nailed It here until June 25.

One of the things that struck me as I was watching the film was that we’re all familiar with the stereotype of the Vietnamese-owned nail salon, but we didn’t understand the historical context behind why these businesses flourished. Nailed It is not just a film about contemporary nail salons but also looks at a chapter of Asian American history and helps us to understand one way in which refugees were able to survive in the US. How did you decide on which historical references to include in the film? What was the research process like during production of the documentary?

Adele Pham: There’s an abundance of directions this film could have turned. I tried to convey the breadth of a 45-year history, which tells a larger story about an entire population of new Vietnamese Americans within our lifetime. The economic impact the salon had on Vietnamese refugees turned nail salon workers is huge. But not all Vietnamese want to be associated with that struggle. And it was class embarrassment that kept me away from the salon growing up. Objectively, however, this is an industry that has sustained countless families, who can literally trace back to waves of Vietnamese immigration in the 80s and 90s, and was sparked by the earliest Vietnamese refugees to escape Vietnam in 1975. That’s remarkable.

There hasn’t been a socio-economic study of Vietnamese Americans and nail salon work over the past 45 years, so I find myself building historical context in tandem with producing the film and distribution. This is the struggle of the working class documentary filmmaker to be heard. But our stories are fascinating and need to be preserved, before they disappear in time. What we’re experiencing now with Covid-19 is proving once more that things don’t stay the same forever. It’s unknown if Vietnamese will always be the dominant players in this industry. I was just reporting the story as I learned it, and what resonated most for me through years of observation.

In the documentary, you mentioned that you had a tangential relationship to nail salons on your dad’s side of the family but generally it was a world of work that had not interested you very much—in fact, it was a place you had avoided. How did you find yourself making a documentary about Vietnamese American nail salons? What was the journey that brought you to exploring the story of these salons and the people in them?

I’d add I had a tangential relationship to my culture too. When I was a teenager growing up in Portland, Oregon in the mid nineties, I was more concerned about how the dominant white culture perceived me. Doing nails is a body service industry. Nobody really wants to scrub people’s feet, and nail art wasn’t as appreciated as it is now. When I left for college and started questioning my own embarrassment around class. It bothered me how little people know about Vietnamese culture, as a “sub” Asian minority. For a lot of Americans we are interchangeable with Chinese. As I’m questioning our classist capitalist culture, in which the Vietnamese were able to ingeniously build and sustain hundreds of thousands of our people through nails—creating an $8 billion nail economy in the process—that became the vehicle for the film to tell a larger story about us.

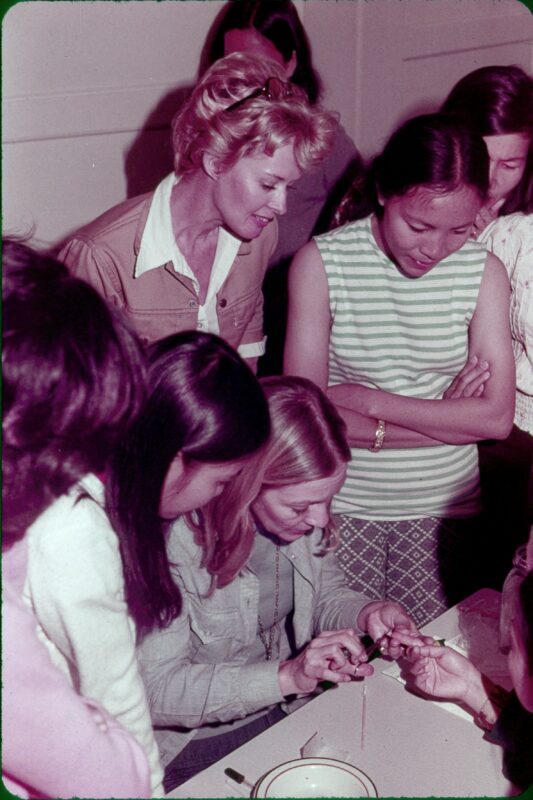

It was so interesting to learn of the connection between the Vietnamese entry to nail salon work and the humanitarian work of actor Tippi Hedren. To be able to see the group of Vietnamese women who have been cited as being the first Vietnamese people to open their own salons was heartening because it was like seeing pioneers of a new life. Were there historical facts or bits of information that you uncovered but was not able to include in the final cut?

In the longer cut of the film I include more of Tippi Hedren, who is fascinating. Stories about her wild cat sanctuary Shambala have gone viral of late because of Tiger King, and her granddaughter Dakota Johnson mentioning it on Late Night. I also included details of Hitchcock’s sadism in the longer cut. Tippi is a fighter, hers is a #MeToo narrative for the record, as well as her resiliency. It makes sense that she mentored the first 20 Vietnamese manicurists at Hope Village in 1975. It isn’t as random as it sounds. The story of the refugee camp itself is also its own documentary. South Vietnamese VP Nguyen Cao Ky and his family (including future Paris By Night MC Nguyen Cao Ky Duyen) were there with the first 20, so the social class these refugees held was different from the boat people who followed.

I had a slick line of VO at one point about Vietnamese Republicans, who believe Regan gave us freedom to immigrate as political refugees—while it was actually Carter who paved the way for the Immigration Reform Act of 1986, ultimately granting amnesty to around four million immigrants who had been in the country since 1982. When Regan signed, there was a shortage of cheap labor in America, which was conveniently filled. And in the 80s many Vietnamese immigrants came from factory work into the nail business.

There is a dearth of data on the health outcomes of these Vietnamese pioneers, although the toxicity of nail salon work is a fixture in media representation. In Nailed It, I momentarily pause on Agent Orange chemical warfare in Vietnam in context with the perceived poisoning of Asian nail techs today. I am offended by how little is known about the health impact of nail salon work. Many people get on a soapbox, but they don’t fight for the science that proves people are getting sick or how to address chemical exposure. In a weird way the fallout from Covid-19 may help the salons that can survive, produce cleaner breathing zones for their workers. Politically I could have gone further, but at the same time this isn’t Shoah. I wanted to make a film that sparks joy in the audience, and I think we succeeded, while keeping it real with the facts.

It’s obvious that you had poured a lot of devotion in making this documentary, it felt like you were not only looking into the history of Vietnamese and American nail salons but also exploring a part of yourself. In the process of making the film, were there unexpected things you had learned about yourself? Did you have expectations or hopes of what you’d like a viewer to take away from the film?

I tend to make films that affect my life. You have to be lowkey obsessed to make a good film, and I think I had an ulterior motive to connect with Vietnamese people. You don’t get more Vietnamese than a damn nail salon and I went into my feelings about that. I wanted to understand why we’re here in America and put that on the record, and nails is the gateway.

For me, one of the most critical points the film makes is that without the Black community, the success of the Vietnamese salon would not be what it is. With the anti-Asian backlash we’ve been hearing about or experiencing during this pandemic, the intercultural relationships inside the salon, specifically with Asian workers and their Black clients, matter. Our generation needs to smash this divide and conquer BS. Nailed It presents the origin story after Tippi Hedren and the first 20 Vietnamese manicurists, as something that was rooted in a partnership between a Black woman and a Vietnamese woman who opened the first chain of Vietnamese nail salons in South LA. We need to get back to that level of solidarity.

Contributor Bio

Amy Lam is the Deputy Editor for diaCRITICS.

Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing, donating, following us on Instagram or Twitter, and sharing this post to your social networks. You can also join the conversation by leaving a comment!