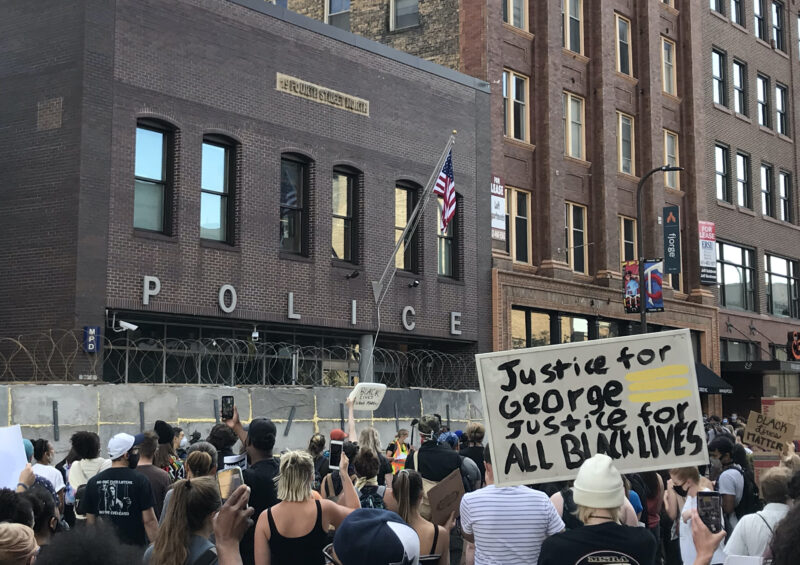

Every night I fall asleep between 4 and 5 a.m. to the lull of the helicopters circling the city and police cars whisking down the blocks to serve and protect its citizens. I have grown accustomed to the hovering choppers and the wailing sirens racing down the city blocks; they have synchronized with the chirping of the birds to dull out my restless thoughts. All you are left with is the smell of capitalism deteriorating, creeping through the window to let you know that revolution is on its way and you can rest your eyes for at least a few hours. I started writing down my thoughts on the fourth night of the civil unrest in Minneapolis where people are demanding justice for George Floyd.

If you are a white reader, please stop reading and think about your intention with this space, or any space — what you want from me or this article. I am not here to give you a live feed from Minneapolis; I am not here to give you a quick and dirty history of systemic racism; and I am not here to perform my traumas for your woke-post. Do your homework – here is a cheat sheet. Your mining for resources and knowledge can be just as dangerous and problematic as the material and labor extractions that are rooted in the founding of this country. You might not commit the same atrocities as your ancestors, but you are still benefiting from their legacies. I am not here to police your whiteness; rather, I am making a space for reflection with my communities, a space for my family who have been left out of the conversation for way too long, and a space for allies who are willing to burn down capitalism and fight for racial justice equity.

If you sense anger, you are right. That is why I am writing. I am also writing because I am tired. I am writing because I am sad. I am writing because I do not know how to express the millions of emotions exploding inside of me. I am writing because once again it is 2 a.m. and I still hear police sirens hunting protesters. I once knew the difference between gunshot noises and fireworks, but right now they are just soundtrack samples synchronized between reality and the livestream on my computer. I am also angry because I do not know how to explain to my family that the American Dream promised to them is the very reason why they are displaced in the first place. Understandably, personal reflections are not indulgent practices meant to focus on emotions but a space to clearly think about the present moment from a personal vantage point or social location. So, if all you are noticing is my anger then once again you are missing the point why this reflection needs to exist in the first place.

###

I have been in Minneapolis for less than two years. I was once told that it is not just me picking the place, but the place has also picked me to be a part of it. Every time I tell people that I live in Minnesota I always get the inevitable question of why followed by their best impersonation of a Midwestern accent. Of course, the weather and cheese curds are also a staple in every conversation. I must admit growing up on the East Coast, hearing “bag” pronounced with the suppressed “a” and drawn out “g” like “bay-g” or “bay-gel,” is heartwarming and novel. But, the why-question is really—why would a person of color move to the “heartland of America”? Peppered between nervous chuckles, I give my rehearsed answer of “this” and “that” while wishing I had the courage to say it is because of capitalism, imperialism, and an endless list of other problematic “-isms” that have impacted most of my life decisions. The conversation usually ends up about why I am in the US in the first place (which is often the real question). I do not have the time or energy to explain to these interlocutors how US imperialism and militarism are the reasons why my family and I are in the US twenty years after the US War in Viet Nam. Also, the amusement with the Minnesotan accent is not just a novelty but a personal coping mechanism to allow me to deflect the onslaught of racist questions about where my accent is from… “it sounds almost like America.”

This tactic of disengagement, however, does potentially reproduce another act of violence that erases the existence of queer Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) within the Midwest. Insert institutional diversity statement with inflated numbers about multiculturalism. In reality, I have engaged with just as many queer BIPOC community members in the Twin Cities as I have in the Bay Area or any other “progressive” cities (disclaimer: I mostly stay within the Twin Cities and on campus so my daily encounters with queer BIPOC are highly curated). As a transient, I initially resettled to Minnesota because of the university, with very little knowledge of the place besides two short visits and a handful of pop culture references. However, it is uniquely being on homelands of the Daḳota people that has allowed me to think about the intersection of Indigeneity, Blackness, and (im)migration. As I grapple with my own refugee/immigrant positionality within my academic work, my physical presence here (both in the US and Minneapolis) is deeply tied to the violent history of the US nation-state being built on stolen land and free labor from chattel slavery. While these terminologies and rhetoric have very high social currency with academia, they have very little impact for my family as they are mostly concerned with whether there are enough Vietnamese and Southeast Asians in the Midwest.

My parents, like most first wave and older generation Vietnamese, are extremely anti-Communist (translation: they are pro-anything that is not Communism). As immigrants, my parents risked their lives to escape one oppressive regime only to be paradoxically folded into a repressive capitalist machine. For almost three decades, my family has been settling in a post-industrial inner city that occupied the stolen land of the Golden Hill Paugussett Indian Nation, where over 40% of the population is Black or African American (Census 2019). This historic seaport city is known for its political scandals and bankruptcies. With great irony, I often have to explain how it is possible for my family to live in one of the richest counties in the country while simultaneously residing in one of the poorest cities in the country. Wealth disparities were our bleak reality; escaping poverty was our vision board. So, as a survival mechanism, my parents worked menial jobs with the hope that the American Dream would be afforded to my brother and I. It has. We both have an education, some degree of job security (before COVID), and comfortable lives. They escaped poverty once in Viet Nam, they expect my brother and I to escape it again in the US. So, the idea of eradicating capitalism is not always a part of my parents reality as it is the lynchpin to their socioeconomic mobility. However, like and unlike the poverty in Viet Nam that was caused by a devastating war, colonialism, and imperialism, the poverty in the US is sustained by an ongoing war against Black and African Americans, Indigenous peoples, and those adjacent to it.

![Graffiti on the side of a white building that reads "2020: The Year We Fight Back," "Fuck America," "Fuck [heart emjoi]," "Fuck the thruth," "Floyd," and "Justice"](https://dvan.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/IMG_3051-800x600.jpg)

###

Over three weeks have passed since the murder of George Floyd. The national guards finally cleared the convention center, the helicopters have intermittently flown to other cities, and my bedtime is still 4 a.m. I know it is ill-suited for me to say that the city was a war zone as my parents lived through a war, but I cannot seem to shake the images of tankers and jeeps weaving through the city streets escorted by police cars and fire trucks waving at pedestrians as if they are in a parade on the fourth of July. Much has changed – the defunding of MPD is on the horizon, racist statues are being toppled, cancelled politics are in full force, and the list is long and plentiful.

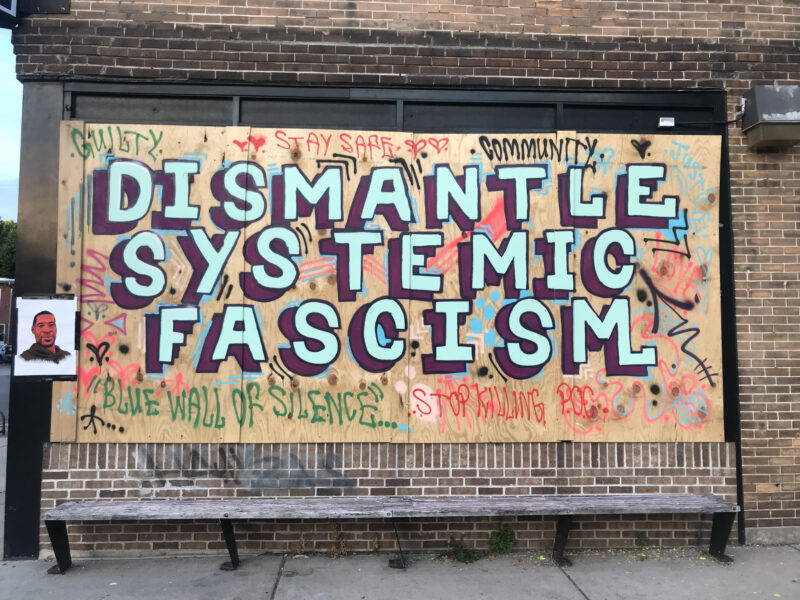

But as corporations release solidarity statements with the hashtag BLM and businesses slowly dismantle their 4×8-foot sheets of construction-grade plywood with haphazardly tagged love, unity, justice, and community, capitalism once again manifests itself from multiculturalism and diversity into solidarity statements. While it is a no brainer to side with the anti-racist movement, dismantle sexism, and eradicate white supremacy, it is another story to talk to your family and loved ones about why and how anti-Blackness is directly linked to their displacement as Vietnamese refugees/immigrants. Solidarities cannot be limited to the Black communities’ support of the welcoming of Southeast Asian refugees, nor the coalition between Asian and Black communities during the Civil Rights Movement. Solidarity across the colorlines will not sustain the movement against white supremacy as racial categories were created to separate people in hierarchical order. I know radical changes and genuine security take time and patience. But so does capitalism. Again, capitalism is not always a bad word. Capitalism afforded my family and countless others material and political securities. This programming is brought to you by The American Dream. Capitalism does not always need to enact violence through stealing of land or subjugating people to inhumane working conditions. Uniquely, capitalism has the capacity to remake war-torn refugees into model minorities that further demonize Black bodies and erase Indigenous peoples and histories. Capitalism are these hashtags and solidarity statements; the myths of upward mobility for immigrants and BIPOC; and endless other opportunities.

To enact changes, we must move beyond silo solidarities that are filled with broken promises. I am not writing anything fresh or innovative. Black feminists, along with Indigenous and feminists of color, have been writing and talking about radical intersectional coalition for decades. When the US expanded its empire at home and abroad in the name of democracy and freedom, capitalism was the engine and racism was its fuel. Correspondingly, the US military occupation in Southeast Asia, Central America, the Middle East, and other regions of geopolitical importance is built on the similar logic of extraction and exploitation that was used against Black and Indigenous peoples. The coalition built on superficial struggles between communities will not be enough to dismantle capitalism. By saying BLACK LIVES MATTER it does not take away from refugee and immigrant struggles but only exposes the structure that created the disparities in the first place.

Thus, as I invoke George Floyd’s name, I am not claiming kinship nor making grand gestures across the racial lines. We are no more than two transplants who lived in the same city a couple miles apart. I say his name in solidarity with Black communities as I say Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, Nina Pop, and countless other people whose names have already fallen out of the limelight or whose stories did not go viral….to honor their life and legacy. When I envision what communities look like I see individuals showing up for each other, talking to each other, doing the hard labor to bear the burden for each other. I also understand that performative solidarity is not enough to topple over racial capitalism, where we need to recognize the layers of racism and colorism within each individual community; in addition to the sexism, transphobic, homophobic, classism, ableism, and on and on. In this work, there are far more well articulated and beautifully written works that deconstruct racial hierarchy across racial lines. I am uplifted by the willingness to work against deep rooted racism that is built on anti-Blackness. But, public memorialization cannot be the end of coalition building where communities also need to create spaces for each to heal, organize, rest, and other sustainable tasks.

I want to end with a note to my family. Yes, I am ok. I am sorry I have not been updating you on my daily activities, I know you will lose sleep if I tell you what I do daily. No – I am not in the forefront fighting the authority, I am not leading a revolt. I am just sitting at my kitchen countertop eavesdropping on radical women talking about their lived experiences and how to make structural changes. Instead of just the kitchen table, the marketplace, or communal spaces, they are also organizing and gathering on main streets and online. This moment of two global pandemics—Covid-19 and racism—allows us to see and move toward the possibility of a more critical world. Arundhati Roy brilliantly wrote, “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.” With that, I want us to witness this historic moment together and imagine a better world where our stories no longer depend on the oppression of others. I want us to live in a world where saying BLACK LIVES MATTER does not make you feel like we are losing ours.

Like you, they are changing the world by changing their world.

June 18, 2020

Additional resources:

- Here are sources that will hopefully start hard and difficult conversations:

While we think that abolishing the police and the police state is impossible, however it is possible.

MPD150: working towards a police free MinneapolisRadical thinker who has done the labor to share her stories.

Nisa Dang – On being Black Amerasian - Solidarity is often fraught with anxiety. Onishi asks us to think through the importance of being in relation with each other.

Yuichiro Onishi – A Politics of Our Time: Reworking Afro-Asian Solidarity in the Wake of George Floyd’s Killing - It is hard to think about the love and labor that are poured into a dream, but dreams can be rebuilt, lives are irreplaceable.

Kim Tran – Talking to my non-Black Asian Mom About Property Destruction - I did not understand why Minneapolis chose me but I am here to learn.

Su Hwang – Letter from Minneapolis: Why the Rebellion Had to Begin Here

Author Bio

Khoi Nguyen (they/he) currently lives in Minneapolis with their dog. Their hobbies include, but not limited to, eating and exploring the city.

Khoi Nguyen (they/he) currently lives in Minneapolis with their dog. Their hobbies include, but not limited to, eating and exploring the city.