The definition of “ajar” on Etymology Online reads “slightly open, neither open nor shut” and the word root points to a term for “turn” (“char”) from Old English or possibly Scottish: the image conjured is of something slightly turned, an object resting at a tenuous angle, perhaps askew of its usual position. A gate not completely latched. A temporary access; an opening.

What passes, what transmits, through this opening? It can be argued that reading requires a state of such opening, opening oneself not only to the interior of the book but also of the one who authored it, whose own interior–thoughts, beliefs, desires, losses, musings–are poured into the words we read. Dialogues between people require a similar action of opening toward “the other”, a willingness to hear, encounter, receive. This manner of opening can be tricky to maintain as it requires us to poise ourselves in a slightly irregular, neither-this-nor-that position: turned. The poignancy of such openings becomes all the more heightened when we add in factors of distance and difference; be these differences of history, experience, political and/or cultural belonging, ideology, nationalities, identities or geographies born often out of consequence more than choice. And, it’s not always possible to manifest these openings–these “ajar” spaces–in physical reality, especially across large distances and troubled borders: thus does the book become a vital vessel and vehicle for “ajar”-ness, due its ability to transcend time and space.

The book enables us to meet asynchronously, non-physically yet intimately.

AJAR Press is an independent experimental and multilingual poetry press based out of Hanoi–founded by Nhã Thuyên, a Vietnamese poet, critic and educator, and Kaitlin Rees, an American translator, editor and writer–a publishing effort founded very much in the spirit of ‘opening’ and openness between different “others”. AJAR is unique in being an independent press in Vietnam, which means they publish apart from, despite, excluded from official channels (i.e. state-approved) that writers must typically go through for the printing, publishing, marketing and selling of books. Censorship can be a somewhat elephantine topic in regards to publishing in Vietnam, and, from the diasporic perspective, we might not fully glean the nuances of what it is like to live and write and publish from/within that environment on a daily “choiceless choice” (as Nhã Thuyên describes it) basis. As a poetic publishing entity that has managed, however tenuously or temporarily, to exist and emerge from and within Vietnam today, AJAR (intentionally or not) presents a perhaps less obvious mode of fighting and resisting, through a mode of not (appearing) fighting, of just being, through existing, playing, coexisting, creating, in their words, “a space not in reaction to or against, but in parallel to and at a distance from the narrow confines…attempting to suffocate poets and poetry”. And/yet: AJAR does not make those “narrow confines” nor the dynamics of opposition the primary subject matter of the poetries they publish. Instead there is another tactic at work here. Asserting only smallness or what they sometimes term “marginalized subjectivities”, they abide interestingly, carefully yet candidly, within a paradox. This seems a tactic, also a conduit, to permit both survival and transmission.

The following interview with the two heads of AJAR unfolded over several months, during which time in each of our locations the Covid-19 crisis has escalated and/or de-escalated and re-escalated, closing and reopening and re-closing borders; also in that time one of the AJAR editors birthed her first child in the midst of her city’s pandemic surge. This interview, I believe, reflects the organic and gently persevering spirit of AJAR’s endeavors at large, a process that knows well the need to move between being ‘extremely open and extremely closed’, for sometimes pausing, resting, resuming, maybe. The world will continue to be riven with its troubles, and our interactions across “othernesses” challenged by many obstacles, concrete and invisible. What is the role of poetry, the role of publishing, amid such turbulences, such ongoing openings and closings? What is preserved by the small, the willing, the very human-fueled efforts? What does being “ajar” in this time really mean? AJAR opens us momentarily (or lastingly) into some small albeit-large spaces for encountering and pondering. [—DS]

diaCRITICS: To start in a simple place and at the beginning: can you tell us about how you two – the founders of AJAR Press – first met? What drew you together, and into collaboration? How did AJAR as an experimental, multilingual, independent poetry press come into being?

Kaitlin Rees: I want to look back to the very first few emails we exchanged, to remember how you first addressed me quite formally with my first and last name, and I addressed you quite mistakenly with only half your name, how you apologized for your toddler who made noise during the poetry reading–the same one who has just turned 10 years old!–and how there are probably certain sentences we were writing to each other back then that have not changed at all in these years, like: “Do you want to sit for coffee somewhere?” Perhaps AJAR as an experiment began like that: a desire for coffee and conversation, a desire to reach across from our respective sites of misunderstanding and see what happens.

I think there must be a brave trust in the other, and/plus a more vulnerable need for that other. We had been meeting for coffees, reading together, and sharing poems for several months before “AJAR” as a choice to publish multilingual poetry came into being. A juncture of life when decisions are possible is also perhaps a juncture of life when such decisions appear choiceless, when it seems there is no other way. At that time, to publish independently was more of a choiceless choice–with a very difficult situation for Nhã Thuyên unfolding in 2014, when her name and work came under intense slander by the State and its diligent hands, and she was effectively blacklisted from all Vietnamese literary spaces. I will let Nhã Thuyên share more about that time, or not, if she wants. But for me, AJAR from the beginning meant opening a space, even just a tiny crack at first, for breathing and play and imagining, a space not in reaction to or against, but in parallel to and at a distance from the narrow confines that were attempting to suffocate poets and poetry.

Nhã Thuyên: The memories of the days and nights with you in Hanoi breathe a little life into my shrinking body of the now, when I am constantly questioning how I can nurture a sincere relationship to (my) languages (and, if any, to literary communities). Somehow an unavoidable and necessary withdrawal (from what/ and to where) makes sense to survive my own feeling of what I want or what’s possible for me to follow. I know I wanted to make more things, and I wanted to fight against my imagination of making more things as the world somehow becomes so crowded, so tiring, so “fake” to my eyes that I am unable to see things well. I long for more empty space to just sit still and breathe, however I keep reminding me of what is still on my to-do-list of the everyday.

What did bring you here to meet me, and what did bring me to you? Is that a poem, or a cup of coffee? An essential happening, or a chance, or an essential chance?

We became closer around the time I was “experiencing” an un/ /predictable storm (or rather, I didn’t notice its early warnings) of literature, not only with a closure of a teaching work in my university. This ending, perhaps unavoidable, wrapped up my personal dilemma in digging into academics conventionally. I’ve become “officially” living (on/for/with) the margin, away from all kinds of institutions and offices, and perhaps forever in the struggle of being in-between, the insecure of being unapproved, of being illegitimate, of being an unconventional and out-lawed word. My body was violently cut into different parts, without any chance for real conversations/ dialogues, what I hoped for. Why love hurts. It does. My tiếng Việt, the Vietnamese language hurts, and was hurt. This still feels so present an open wound, not yet a healed scar. Could I be able to survive this violence? Could It be a gift for my youth, to grow? Carrying unknown consequences along a little body that was brutally exposed, my Vietnamese language body has been estranged and I felt unable to be in “normal communication” again for many years. I was silenced, and I silenced myself in the language I live with, as the language sometimes demands us to test our minds in silence, to make wars in silence, to find peace and calmness in silence. It’s not about being courageous. Or perhaps I am gifted in being silent, inheriting our “tradition”. But my stubborn [choiceless] choice of writing, which is not different from living, nurtures in me the resilience in languages, to keep learning the language of my own, of my mother-country, and of others.

My hopes and questions for AJAR are not separate from my hopes and questions for the Vietnamese language in its survival from all violences of the past [I am pessimistic and not exaggerated] and in its encounters with the other’s languages. [How to love & to survive in this language?] [Is it possible for me to love as many languages as I can?] [ Am I / Is this language able to be an ajar door?] [Is it possible for this language to be with the world? Which world?]

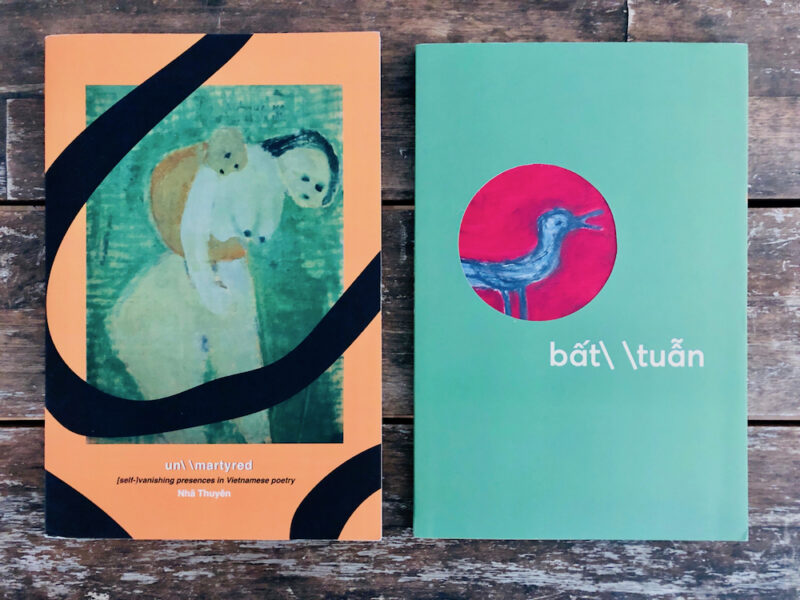

Recently, finally, my long-abandoned manuscript on Vietnamese marginalized poetry and poets has transformed into this body and quietly goes into life, bất\ \tuẫn, un\ \martyred, first in English translation published in the US, and then I SPOSD – self-published on self-demand – in Vietnamese, with the support from Hanoi Goethe Institute, to hand-reach to a few hundreds readers here. This Vietnamese edition doesn’t mean I have a clear answer for myself in any way for what happened in the passing years personally, neither do I need to prove anything to any others, but the book witnesses my enduring relation to tiếng Việt, and perhaps saving a little pandora hope for the poets, writers, and especially for the readers of this language. I recall Edmond Jabès a couple of times, though I am not at all a writer as witness, “having the book as witness” “is having the entire universe vouch for us”.

Perhaps if I was less ignorant, I would be choosing a different way that would surely lead to other paths of writing and living. But at the moment, I am still wading on this tiny path, with ajar, with languages, between people who are leaving and who enduringly stay, here and there, with all the struggles of the everyday and of every dream.

Perhaps I was not ignorant enough.

DS: AJAR Press publishes a journal, a catalog of books, and a bilingual series of small poetry books, the Fish Eyes Series. For those who may not be familiar, can you tell us about your catalog and how many books you’ve published to date? How often does AJAR Journal publish? And which came first, the books or the journal? How many languages do you publish in? What are the different countries your authors have come from?

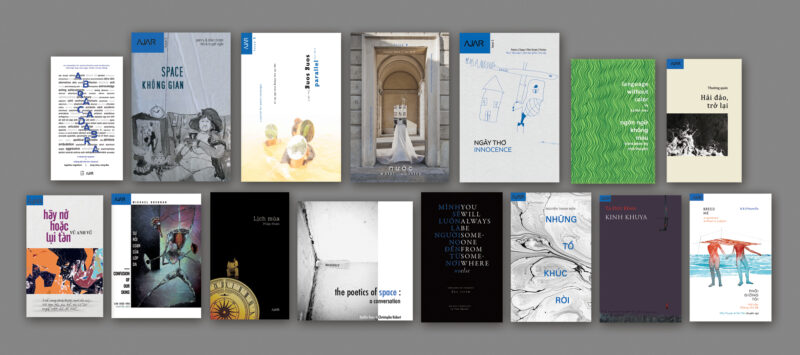

KR: How often does AJAR publish–yes, we are asking ourselves this too! To date, we have published five journal issues (with the first one being online at ajarpress.com only), nine single author collections in the Fish Eyes series, one book of essays and one anthology of poetry from our A-festival gathering organized in 2016 and 2017, and a few chapbooks along the way. The chapbooks were first to come and we are hoping to return to this spirit of publishing shorter and more experimental collections, to encourage certain writers we love to keep going. The journals have grown in scope and ambition since the beginning, each one becoming larger it seems and bringing in more and more languages. Our last issue, song song || para||el included Tagalog, French, Burmese, Vietnamese, Spanish, Indonesian, English, and Chinese languages, with some complicated design elements that entangle them as much as possible.

NT: Beside the issues, ideally we hoped to publish 3 fish eyes books each year (one poetry collection of a Vietnamese living inside, one (originally) Viet person (if this word is possible for a name) living outside Vietnam, and one from other languages translated into Vietnamese). We want to make all books (almost/at least) bilingual, take care of the translations as well as the beauty of the books as poetic-objects. However we only can follow our heart-mind-beat and the chances of seeing good potentials to publish. I am also more aware of what should be printed and what should less be printed, and not in a hurry to make more books for this already too crowded world, as always there are so many good books waiting for us to be read. AJAR books depend much on, and realise/ visualize the encounters with writers and readers and their readership. Books will come when they come and I am more prepared now. In a hopefully countable future (a noun), I’d love to explore printing experiments, play with chapbook and handwriting forms, and perhaps make some posters, postcards, poetry-drawings, and such nonsense. As for our authors’ countries… I always wait for more fresh voices from Vietnamese languages/ relating to questions of (plural) Vietnam. But where do you come from, I may ask…

One thing I am clear with myself: I don’t want to direct AJAR toward a professional press, with the idea of joining the book industry. Presently, I want to grow smaller (and one day come to a beautiful disappearance, perhaps?), with sincere care for the authors and the books we choose to publish/the things we make, and also considerate of whenever we are able to be publicized. How often does AJAR publicize ourselves?

DS: How key is/was the location and presence of Hanoi to your publishing collaboration? I understand that many AJAR activities and projects were birthed and nurtured from long coffee sessions at Manzi Cafe, and that it all bloomed very organically. I’m curious whether this collaboration could have happened elsewhere than Hanoi; it seems like a very special time and circumstance created it. Could you tell us a bit more about your work/publishing process in those early days? And what does location (home, place, a shared space) mean for AJAR now and looking forward, with Kaitlin presently in NYC and about to have her first baby, and Nhã Thuyên still in Hanoi?

KR: I open this question from behind the bleary eyes of my first week of momhood, in a city that has radically transformed since I last set foot in it a week ago, before my postpartum bedrest and New York’s pandemic quarantine coincided in two very different kinds of stillness. Perhaps the way a baby seems to make time pass more slowly, more wetly, more nonsenibly, more ignorantly, detaches me from the reality of place right now, as does the long period of isolation, and it’s natural to remember what it is/was like floating in that other time and place when AJAR bloomed into life. I think physical presence has been and is something essential to AJAR’s process, even though we keep using language around being a poetry press spread out here and there and nowhere, and even though the vast majority of our work occurs online, I/we always stay with the dream and expectation of togetherness. Since moving back to New York, I keep waiting to be again in the same room with Nhã Thuyên. I think of this collaboration as born from a synchronicity and physical energy that is hard to replicate across time zones, though we have been managing it more slowly. The energy of what sparked this work in the beginning was perhaps something of the energy of the city itself, a combination of longing and chaos and urgency and immobility, plus the super strong coffees at Manzi where books were held and passed back and forth across a table. We had our opening launch for the first issue at my house in Hanoi, a house ajar, a structure built in such a way that invited a blurring between inside and outside spaces, with plants and wildlife finding their way into the kitchen and living spaces. And I think that feeling of home (away from home away from…) and its intimacy marks the work strongly. From the beginning, I think everything we did was out of love, young love, reckless love, heartbreaking love, maturing love, enduring love, and rather than ever being strategic about creating any kind of sustainable business, we followed the rhythms of that love. I don’t think AJAR could have been born in another city, or at least not in New York where, to me, it feels like such kind of nonsensical and innocent play tends to (and perhaps must) become defined and professionalized impossibly soon.

NT: Yes, there are always the cities we come to and leave and might never leave. Perhaps it’s because of this city, Hanoi, and because of human relations. Perhaps only here a meeting, even “a serious one” could be planned 5 minutues beforehand with text messages, “I am here at Manzi/Bluebird/, do you want to come over and talk.be silent.read.translate.edit.write… next to each other?” and “the other” (sometimes plural) will be appearing just in time for the very first drops of coffee in my cup (or sometimes a cancelling text on the way?). How many different tastes of coffee can we remember? How many times did we move from this coffee to another? How can I count the deserted nights filled with yellow lights on the streets, our noisy thoughts and dreams of collaborations and communities calling, demanding us to be more resilient, more stubborn? I remember those late nights after books home from the printer, and once we sat on the street having a beer to welcome them quietly, crying a little cry somehow for our tiptoeing feets on this ground, for what appears to be “totally joyful, playful and amazing” in some others’ eyes. We all know the labour and many friends supporters behind. And perhaps that’s why we could keep some words as mantras: be stubbornly ignorant, be patiently beautiful. There were some too-hopeful-moments, everything appeared possible, more possible, more breathable and I was perhaps impossibly possible, to be in and with the way I’ve learnt to trust, and I’ve chosen to not censor the possibilities and/or the illusions of living illuminated in my body. A few years felt like a decade, condense, full of excitement and bồn chồn, “dreadful hopes” in Kaitlin’s translation of my poetry. We were perhaps young enough and hungry to be open and welcome others, longing for others to fill ourselves, and we’ve learned (perhaps too much?) from mistakes and misunderstandings. You said to be ajar perhaps too difficult, and why we chose the way sometimes unbearable. But I am not sure now we are less innocent and reckless.

tôi biết điều sẽ không trở lại nhưng không biết điều sẽ tới.

[How did you translate this sentence, Kaitlin?]

(KR: i know the things that have yet to come back but not the things that have yet to come.)

These living memories make our past also present.

Each city has been built and dissolved with some significant presence and absence, at least it’s how I’ve been thinking of them. We couldn’t simply erase the reality that had been there, and something was born. I still live with my indirectionable questions of locations and movements, of leaving, of staying a bit more, of living in the plural of place, of moving around this (un)world, of hiding somewhere there are some blood-felt ones and lots of “professional amateurs” who would be ready and even take risks for some nonsense, of desiring a place in between being connected and not necessarily being known. Of a “physical” ajar house. If my body can bear many more years to come, who knows what may happen? But we all know there is a place where we started and grew, even if growing apart.

Now I am still here, waiting and not really waiting, and a me of some years ago somehow is no longer here, in this city now more deserted, more absent, more depressing, quạnh quẽ hơn, accepting that it’s already another stage of life, another space-time, even another life. And It could have been another different life. Sometimes the lines of Emily beat in my tongue, with Bùi Giáng’s Vietnamese translation:

Parting is all we know of heaven,

And all we need of hell.

………………………………………………….///Vĩnh ly là chất của trời

……………………………………………………..Vĩnh ly là thói của đời nhà ma

We didn’t mean to stay apart and do things unaccompanied from afar. Oddly enough, I decided to conduct some workshops among a handful of young people, tôi (cùng) đọc thơ tiếng Việt [ I (with you) read Vietnamese poetry] & tôi viết (tiếng Việt) [I write (Vietnamese language)], that was just before the lockdown- so we’ve been maintaining mostly online- without Kaitlin, without making it a publicized activity of AJAR, though still, it’s very much an ajar way. All these kinds of “literary activities” were supposed to be with AJAR people/would be much more open in languages if Kaitlin were still here and/at least not thousand of miles apart and two time-zones. Personally these workshops help me to reconnect to the Vietnamese literature and people, of the past and the now, of the inside\ hải nội and hải ngoại \ the outside-the-sea, and to meet some new faces of young people who somehow see in me a friend they can trust. I felt alone, and also it’s an essential loneliness for me, to be with my inner demandings to re-learn my languages.

But we still hope for a better future (whatever that means), even if this is not a hopeful time for physical connections. We have the next issue of AJAR waiting to be edited, and a bilingual poetry book by Samuel Caleb Wee, a Singaporean writer, with the translation by Nguyễn Hoàng Quyên, for the Fish Eyes series. I want to make some print experiments with the materials from our workshops. We also wait for Kaitlin to be back (with her attachments) when AJAR can be more physically active among our communities. We’ll plan for book launching events and gatherings, reading and performances as before, though a reunion of all people as before would be more impossible.

Being an “independent” press in the U.S. may hold a different weight than in Vietnam, I suspect, in that I understand most publishing in Vietnam must be state-approved. In the U.S. “independent” usually means simply that one is not affiliated with an institution or corporation or major publishing house; the main challenges are funding and visibility (and the general indifference, perhaps, of a more commercially oriented readership), but not necessarily state pressure. I know this may be a sensitive question to ask, but I am wondering if you might be willing to elaborate on what being “independent” means or has meant, for AJAR, as a publishing endeavor in Vietnam?

KR: I think it means the same in Vietnam but the implications and consequences and even legality of printing materials outside of institutional or state support/consent carries a different weight. As I understand it, which is an understanding threaded with ample misunderstanding, independent publishing in VN is not illegal but is a punishable offense and subject to harassment and surveillance and even disappearance of books deemed unfit or if those books do not have state permission from the cultural censorship authorities. It’s complicated to know precisely what the rules and risks are, as I think there is so much grey area in these matters, and if a press like AJAR is small enough and unfamous enough, it can slide through into some unofficial marketplaces like cafes and art spaces and the very few bookshops that are willing to shelf them. It wouldn’t be difficult to get (purchase) permission for our publications as there isn’t, to my knowledge, material we publish that provokes state censorship. It is more the act of not subjecting oneself to that position of asking–that desire to not kneel down is the provocative act, not the poetry itself. When we started to distribute in the US and needed to purchase ISBNs, it gave us pause to consider how we are fine with purchasing the right to sell books in the US/internationally but are not fine with purchasing the right to sell books in Vietnam. The difference is in the asking, the kneeling.

NT: I was idealistic enough to make things with the belief (that of course comes with plenty of questions) “if this should be normal for humans everywhere, it should be/should it be possible for me to make it (to live it) even if it still appears abnormal here”. THIS is not just for (indie) publishing. Of course I did research and learned about the problematic condition of publishing in Vietnam, especially all the systems of prior and post censorship. I do want the feeling of being free officially, of being recognized and approved normally, of being able to work with printers and booksellers to make and sell our books, of not being scared of intimidations and warnings. I am not scared, as I know my right-choice to question what I think needs more questions. In sort, for this choice of publishing independently, it’s not ABOUT censorship as some understanding/some facts taken for granted here. I want to practice more ways to equally co-exist and what matters to me is not about finding some (seemingly good) models to follow. Thinking of what we habitually/conventionally call “freedom of expression”, I think it needs to be a responsible practice in every detail of what we really want to make better, for readers and writers and books.

One of the first things that drew me to AJAR, that I felt instantly even via the remote auspices of the internet, was a spirit of playfulness and sincerity, also a dedication to the experiment, to language and liminality, and a positive embrace of the nuances and precarities—those things hard to pin down—about creativity. I get the sense that AJAR both welcomes and questions, to healthy degrees, and is aware of the borders and boundaries you all are working within/across/beyond, even playing with. It occurs to me that part of the journey or challenge of “being ajar”, and staying in that “ajar”-ness, may have to do with keeping alight, also, this spirit of play and porousness; a sort of bright-eyed openness toward the very experience of reading and sharing. I am struck by these words from NT’s essay [from We Now, Here, There, Together]:

“Expansion of the self lies in an encounter, not a reinforcement of privilege: we always need to converse, to meet five or ten more readers and converse. Or more simply, our dear friends are speaking a language and we would love to bring our language over to converse with them… The distance between languages connects living curiosities.”

I love so much in this. It’s a simple and welcoming statement, yet there’s also a profound suggestion in here about openness—“living curiosities”—as being perhaps key to a vital form of (r)evolution, or at the least as a way around/beyond much of what has divided us or closed us off from one another (and I leave open here how this “us” is to be defined–whether it means different types of Vietnamese people encountering one another, and/or Vietnamese people encountering other nationalities and cultures of people too). Can you speak in your own words to what “ajar”-ness means for you, as writers, translators, publishers, as two people working together from two different cultures? Or/and, if you’d rather, could you simply tell us how the name for AJAR Press came about?

NT: How to speak about our desire outside being exposed this way or that, extremely open and extremely closed, and gradually ajar again, one more time, be ajar, be a jar, be aaaaajar.

KR: When NT says above “there are some moments in life when it’s possible to be in this world”, I think about the moments when it’s not possible to be in the world, when retreat from is/seems the only way to be. Perhaps this collective quarantine time is one of those extended moments when staying inside, staying unseen, immersing inward, hiding in the little corners of selfhood you don’t/can’t show to anyone else, is just what must be done. Though I hadn’t read it before we decided on the name of AJAR, Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space has one sentence that resonated much with me in those early days–human is a half-open being. What I take from this formulation is the constant motion across a threshold of inside and outside, of opening up the self to step out to be seen, exposed, and then a closing down and stepping back in to be concealed, private–that this sway of being in the world and retreating from the world results in a state of ajarness. I think about translation and the movement across and into another writer’s words, another person’s home, and the feelings of outside and inside language that are constant.

AJAR Books can be found online at:

For international readers: https://ajarpress.fwscart.com

For readers within Viet Nam: https://form.jotform.com/200415998691061

Follow Ajar Press at:

FB: @ajarpress

IG: @ajar_press

Artist Bios

Nhã Thuyên’s most recent books are bất\ \tuẫn: những hiện diện [tự-] vắng trong thơ Việt (self-published) and its English edition: un\ \martyred: [self-]vanishing presences in Vietnamese poetry (Roof Books, USA, 2019) and moon fevers (Tilted Axis Press, UK, 2019). With Kaitlin Rees, she founded AJAR in 2014, a micro bilingual literary journal-press, a precariously online, printed space for poetic exchange. She’s been talking to walls and soliloquies some nonsense when having no other emergencies of life to deal with. nhathuyen.com

Kaitlin Rees is between Hanoi and New York City. With Nhã Thuyên she founded AJAR, a small bilingual journal and press that has hosted two intimate-international poetry A-festivals. Her translations of Nhã Thuyên’s poetry recently live in the Tilted Axis chapbook Moon Fevers as well as the full-length collection, words breathe, creatures of elsewhere (Vagabond Press, 2016). She is currently translating Nhã Thuyên’s self-described ‘nonsense’, a book of poeticized prose that embraces small subjectivities and relationalities, and works at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop to edit the Transpacific Literary Project, a series of portfolios focused on translations from East and Southeast Asia.

Kaitlin Rees is between Hanoi and New York City. With Nhã Thuyên she founded AJAR, a small bilingual journal and press that has hosted two intimate-international poetry A-festivals. Her translations of Nhã Thuyên’s poetry recently live in the Tilted Axis chapbook Moon Fevers as well as the full-length collection, words breathe, creatures of elsewhere (Vagabond Press, 2016). She is currently translating Nhã Thuyên’s self-described ‘nonsense’, a book of poeticized prose that embraces small subjectivities and relationalities, and works at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop to edit the Transpacific Literary Project, a series of portfolios focused on translations from East and Southeast Asia.

[…] week, we published a conversation with diaCRITICS very own Dao Strom and the cofounders of AJAR Press, Nhã Thuyên and K… about what it’s like to run an experimental poetry press, independent publishing in Vietnam, […]