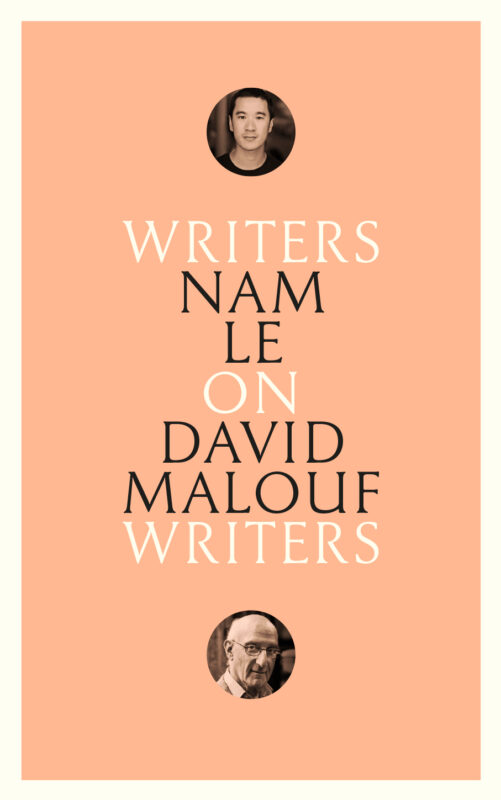

‘A Great Lake’ by Nam Le is an excerpt from On David Malouf: Writers on Writers. Le’s latest book is part of a series where writers reflect on and respond to the legacy of noteworthy Australian authors who have preceded them.

David Malouf was born in 1934 and is widely considered one of Australia’s greatest writers with a highly esteemed body of work. On the face of it, the idea of Vietnamese-born Australian author, Nam Le, of the acclaimed story collection, The Boat (Knopf, 2008), writing in-depth ‘On David Malouf’ is perhaps a little unexpected. But arguably, this is a fresh pairing. In thinking about Malouf, Le uses the opportunity to interrogate, among other things, the contemporary politics of identity.

There was a lot I appreciated in Le’s provocative book. Existing as a Việt Kiều reader and a writer in Australia has always been complex, just as it is elsewhere. When I first encountered Le’s essay in Granta, I found it insightful because he writes about many things I’ve been unsure how to put into thoughts, let alone words. For example, he writes:

“But for those of us who have spent our lives fighting for cultural space, respect, autonomy, equity – the last thing we need is for our accession, if and when it comes, to be asterisked. The system wants us to want to belong, at almost any price. We owe it to ourselves to want more.”

What does ‘wanting more’ look like? We won’t unanimously agree on this – nor should we – but it’s a key question each of us need to answer. Not just for ourselves, but for our communities too. In doing so we will be able to undertake the important work of reshaping and even rebuilding the system, which feels more urgent than ever.

This is an excerpt from Nam Le’s book On David Malouf: Writers on Writers, published by Black Inc, in association with State Library Victoria and the University of Melbourne. This excerpt was first published in Granta.

~ Sheila Pham (Contributing Editor, Australia)

A couple of years ago, I accepted an invitation to be a writer-in-residence at the University of Wyoming. These gigs typically involve a little teaching, a little money, a little time to write. Just before I flew over, I was informed that in addition to my pedagogical duties, I had been slated to appear at a number of events across the state advocating for refugee settlement.

I hadn’t been asked first.

These events entailed being flown in a small single-engine plane to deliver pro-refugee talks in fairly conservative places (in one town, the cops arrested a rabble-rouser who’d put out a podcast call inciting violence), guest-slotting a ‘social justice’ book club, and doing a bunch of media. The worst of it was a PBS TV bit. I could’ve said no but I didn’t, I said this:

I was a refugee. My family was involved in the Vietnam War and . . . when things went downhill, we, like millions of other Vietnamese, fled the country . . . When we were in trouble, Australia let us in and took us in and looked after us. They had no reason, really, to do it; they had a lot of reasons not to. They didn’t know us. They didn’t owe us anything . . . It still does boggle me when I think about that, and it’s not really something that gratitude can cover. It’s too big for that. But what it does bring home to me is [that] beyond the politics and the policies and the very legitimate notions of sovereignty, border protection, of cultural preservation, there’s still this project of very simple grace – of just helping people who need help even though you don’t owe them any help. And that, to me, meant everything when we needed it.

Predictable stuff, right? Most people, I reckon, from left and right alike, would find these sentiments unobjectionable, even agreeable. Most people would be confused by my own reaction to them – for any time I see this clip, I come away with a wretched feeling – a mixture of unease and ire and self-directed scorn. That I did it to myself – let myself do it to myself – makes it harder to bear.

What exactly did I do?

I allowed myself to be used. I became a mouthpiece. I took in vain my plural self to spruik a singular, flat, facile politics. In part, I did it because I agreed with the politics – pinned down, of course I thought/think the US should be resettling Syrian refugees – but my problem was with being pinned down, coerced into answering that question without being free to question the question’s underpinnings, its mess of historical, political and ethical consensions. None of the terms were open to me. How could I in all conscience argue for the stateless, for example, when, to me, the very consensus of the Westphalian nation-state feels unconscionable – a spur to hate and horror? How could I make a case for immigration when I hold the very concept of territorial sovereignty responsible for encoding the world’s deadliest asymmetries? A state is a priori an exclusionary mechanism. It ransoms the human need for belonging against the human wont to tribalism and xenophobia. It justifies the self-interest that justifies its statehood – ouroboros, ad infinitum. A state sets limits and conditions – that is its deal.

All politics is border politics. Sovereignty doesn’t mean much without someone else to shove it to.

On top of that, I loathed the whole set-up – I couldn’t help feeling a familiar vein of bad faith running through all these good intentions. Social justice is easy when it’s low-cost, high-return. Wasn’t this just another way we could all broadcast our progressivism without forfeiting our exceptionalism? (No pro-refugee activist there was proposing open borders.) Wasn’t this just another neo-liberal application of virtue, whereby we could accrue socio-cultural capital through the Having of Opinions without having, ourselves, to forgo any economic capital or comfort? Guilt as vehicle for vanity?

And all done via the amiable, earnest Asian-Australian guest (an ‘Eminent Writer-in-Residence’, no less) who had been there, and even written about it!

This, of course, was the other thing. I had taken in vain my writing self. I had used language in a way that was antithetical to what I ask of my writing: that it come from me, and carry some of my life, and convey my truth (including its uncertainties, ambiguities and antinomies) in as true a form as I can find, wherever it might lead me. What I delivered instead was a maudlin Hallmark ad for my ‘sponsors’, pitched intuitively at the level of coddling and congratulation. I took an issue about which I have insoluble feelings and – having no opportunity to think it down through writing – instead boiled it down to literal propaganda. What candour might have been in it (and of course, in a way, I meant every word) was made performative by camera and context – I felt myself false even while saying what I meant.

At bottom, the failure that wounded me most, I think, was my deference. To the brazen assumption that because I had been a refugee, I would be willing to be identified as a refugee, I would be willing to be defined as a refugee, I would be in support of refugees (whatever that meant), I would be willing to speak in support of refugees. I did what was expected of me. In doing so, I essentialised not only myself but all refugees (who, I know, are as variable, irrational and prejudicial as any other people, including on refugee-related topics). I spoke for others when I wasn’t even truly speaking for myself. We refugees are already trapped in a condescending narrative that promotes asylum as destiny; I failed to resist the denouement that ascribes destiny to character.

*

That moment has come back to me over and over again. It’s taken some time for me to realise its connection to this essay: it’s to do with sovereignty, but of a different kind – personal, artistic, closer in spirit to Bartleby’s ‘I would prefer not to’ or Stephen Dedalus’s ‘non serviam’. A sovereignty that recognises that all authority – under state or religion or tribe, or even under ‘self-evident’ abstractions like legitimacy, public good, or moral or civic duty – is coercive in the absence of clear consent. And consent, obviously, can never be clear in a world wholly consisting of ‘facts on the ground’.

Which brings me to David Malouf. Over a long career, he seems, somehow, to have preserved – with natural lightness of touch – this personal, artistic sovereignty for himself.

He is ethnically half-Lebanese (with some Portuguese strained in for good measure), of immigrant stock, yet has for decades elided these aspects of identity to little note and no fuss. (I cannot understand how, even accounting for generational differences, he’s managed this.) He’s gay but has also managed to stop this from becoming seasonal grist for the queer studies mill. A former academic himself, he must understand that such openings are enticements to academic spits: once stuck, writers can end up turned eternally on the same skewer, basted in the same sauce. Famously private, Malouf has nevertheless intimated enough about himself in his work to ward off too much off-grid digging.

Most impressive to me is his composure; his disregard for fashion or recency (and his collateral disquiet towards contemporary literary ‘scenes’); his comfort in his self and his place in the world. Reading him, you find yourself in an exchange with the courteous stranger at the party who, while speaking to you, looks over neither your shoulder nor his own. He eschews labels and allegiances, schools and groups and movements (‘a mug’s game, a mugger’s game’, he’s called all that). Around about the time my book was published, I came across a quote from him in a newspaper article: ‘I totally reject the idea of being representative in any way.’

Yes!

From the first, Malouf has gone his own way. It’s an ethos so marked it rises to the status of an ethic. In literal terms, it’s meant spending substantial time in England and ‘a place in Tuscany’ (not quite as idyllic as it sounds, but still . . .). In literary terms, it’s meant a restlessness, a searchingness of genre, form and subject that led early (and unimaginative) reviewers to note that his books seemed written by different people. ‘You do what you do, the way you do it’, Malouf said in that article, ‘out of a kind of necessity.’

I know something about labels. My book consisted of short stories that ranged, fairly widely, across settings, styles and subjects. That was what my necessity looked like then. The reviews, mostly positive, were also mostly complicit in common reference to my ethno-nationality – as though no estimation of the work could keep without the seal of the author’s status as ‘Vietnamese-Australian’. I expected this – even anticipated it in the meta-fictional first story of the collection. And of course I appreciate that context matters, that fiction is scored by both its maker and its making, and that interpreting these marks can be instructive, even enlightening. Proust, notes Malouf (while keeping his own mind), ‘is in no doubt that a contemporary writer’s life will be known and is part of the text’.

But how has ‘life’ become so unquestionably shorthanded – short-changed – into ‘identity’? Why should, say, the work of ‘ethnic’ writers – now that overt orientalisation is out of fashion – remain charged with extra onuses of representation, explanation and authenticity? ‘Vietnam’ is a Western war. Is it actually impossible for a work by a ‘Vietnamese’ writer in the West to be evaluated without this unifocal historical knowingness? Without presumed psychodramatic intimacy? Without a framework of imputed, all-smothering victimhood? Auden writes, ‘Of any poem written by someone else, my first demand is that it be good.’ This is how the writers I know and respect talk about writing – in private. (And yes, we know ‘good’ is a contested, contingent term.) My naive hope, I guess, was for my work to be judged the same way in public, unbeholden to the cultural diktat that the more ‘marginal’ a writer’s face, or place of origin, the more central it must be in the commentary. That way lies special pleading – and special treatment.

If literature has a nemesis, it is instrumentalism – the approach that treats it as a tool, values it not for its own sake but as a means to an extrinsic end. This is, I realise now, the language of Kantian metaphysics. Humans are to be treated as ends in themselves, never as means to an end. It makes sense to me that art might warrant the same imperative as people. ‘Identity’ is not nothing, but it’s not everything. What it is – how much it matters – is something for case-by-case consideration. (Another imperative that applies as profoundly to all serious art.) Yes, the system is rigged. It’s built on the circular, stupefying logic of ‘entry by admission only’, which, for so many, for so long, has meant off-limits, no-go, maybe-next-time. But for those of us who have spent our lives fighting for cultural space, respect, autonomy, equity – the last thing we need is for our accession, if and when it comes, to be asterisked. The system wants us to want to belong, at almost any price. We owe it to ourselves to want more.

One term at school, I was chosen as bell ringer. This memory still shines through the murk. I remember the thrill of possessing the empty corridors and courtyards with cause, singled out, special, bearing pass and power to end the given period. I was in charge of all that freedom. I would wait as long as I dared, then swing the rope knotted to the thick brass tongue, swing it hard and regular and skullbreak-strong against the bronze rim.

*

I know something about labels, or my parents do. What follows is a bit patchy, in the way of family histories; I can’t entirely vouch for it. In fact, I can barely stand to write it. I don’t like to write about personal things in non-fictional mode; the truth feels harder to get to. Yeats said, ‘All that is personal soon rots; it must be packed in ice or salt.’ He was talking about the formal conventions of lyric but let’s allow the poet some play: ice hardens the heart, salt poisons – irrevocably – the razed city.

Not so easy when it’s your family on the line.

In the PBS spiel, I said of my family: ‘when things went downhill, we . . . fled the country’. Those first four words – when things went downhill (and what more tritely perfect example of Australian understatement?) – papered over assorted bad things (death, suicide, dispossession, displacement, labour camp, starvation, subjugation), but the common coefficient to all this was a booklet of cheap, coarse, yellowish pages called the Declaration of Personal Background.

Saigon fell; the Communists took over. Law became ideology; your fate as a southerner was pegged to a Party line that twanged unpredictably in response to the internal and interpretive tensions of Marxist–Leninist–Stalinist–Mao Zedong Thought. Those few Communists who claimed to understand the theory spent their time contesting it with each other; the rest went about their usual business: classifying people. The Declaration was a brilliant originary outsourcing of work. It opened everyone’s record: first you classified yourself class-wise (bourgeoisie, petite bourgeoisie, proletariat, peasantry) and then you accounted in detail everything you’d been, done, thought or associated with over a thirty-year time span. This led you to the next rung of classifications (puppet, lackey – imperialist or neo-colonialist sub-types – quisling, comprador, rightist, revisionist, reactionary, or – the catch-all – counter-revolutionary). You picked your poisons.

Then you repeated this process for every single person in your extended family, going back three generations. (Given the size of Vietnamese families, this typically involved over a hundred people.)

The Declarations would then be collected and cross-referenced against each other. You would expect to be cross-examined on what others had written about you. You would expect to be cross-examined against what you had written in your own earlier Declarations – for you were expected to regularly fill out new ones. People learned to keep things simple and consistent. They learned to apply the correct Communist jargon. By way of countermeasure, Communists mandated interminable ‘self-criticism’ and ‘struggle’ sessions; they demanded you write extemporised, in-depth essay after essay. You had no choice. You had to keep producing the words that would be used to sentence you.

And so they were. The labels stuck, and they were fatal. They became your identity and your identity became your destiny. Based on these labels (petit bourgeois, quisling), my father was sent to a ‘re-education camp’, where he was enslaved and tortured for three years. My grandparents (neo-colonialist, compradors) had their homes and businesses confiscated, their possessions commandeered, their savings devalued. Two of them suicided. My mother (bourgeois, lackey) fared better: she was merely relegated, with her baby, my brother, to a crowded garage that had once belonged to her family, and invited to pay her ‘blood debt to the people’ by relinquishing any rights, jobs, civic status or control over her future.

I’m reminded of a bit in Vasily Grossman’s incandescent, excoriating Life and Fate. Our protagonist, a compromised intellectual in Stalin’s Soviet Union, is (of course) filling in a questionnaire:

Viktor wrote, ‘Petit bourgeois’. Petit bourgeois! What kind of petit bourgeois was he? Suddenly, probably because of the war, he began to doubt whether there really was such a gulf between the legitimate Soviet question about social origin and the bloody, fateful question of nationality as posed by the Germans.

The italics are mine.

How far is the distance from ‘legitimate’ to ‘bloody’?

Is this where you end up when you go too far?

*

Early in Malouf’s Harland’s Half Acre, some white boys come across a rock carving:

Not far before the ruins there was a platform of rock. Aborigines had foregathered here, all the local tribes in their wanderings, and left crude rock carvings . . . With their knees drawn up [the boys] would sit on warm stone in the very midst of it, among the sea-creatures and the flights of wallabies and paddymelons and every sort of bird; that other world would be all about them, abstracted into enduring lines that crossed and criss-crossed in an endless puzzle. The outline of a whale might be broken by that of a bounding kangaroo, the separate orders of creation, sea-beast and land-beast, interpenetrating in an element outside nature – the mind of whoever it was, decades back, who had squatted here and with bits of flint or a sharpened stone made the clearing a meeting-place for separate lines of existence.

Malouf’s books abound in numinous moments, but this one stands out for me. The rock carving is a work deeply in and of the world, made by many human hands. There is no separation of past and present, myth and materiality. This is archetypal Malouf in that everything is interconnected, everything liminal, on the verge of metamorphosing into a ‘separate order of creation’. In The Great World, the hero, Digger Keen, says, ‘Even the least event had lines, all tangled, going back into the past, and beyond that into the unknown past, and other lines leading out, all tangled, into the future. Every moment was dense with causes, possibilities, consequences; too many, even in the simplest case, to grasp.’

This is what identity looks like, Malouf is saying, if you must insist on it. It is, at its most basic, indistinguishable from existence, which is, in turn, infinitely complex – a network of tangled lines going every which way, through every part of being-in-the-world. These lines run in and out of place, time, genetics, culture, language, circumstance, accident, other people, all the happenstances of mind-life and dream-life. All a writer can do is stand in the midst of this monkey-puzzle mesh and pluck one line, then another, trying to happen on a harmonics that sounds right. Art comes (or it doesn’t) from these soundings.

What is folly is imagining you could compact these lines into coherence, let alone sense – let alone representativeness. If my family history has imbued me with anything, it’s the awareness that identity is complex, politics is complex. What a disappointment, then, that identity politics is so simplistic. I’m actually not unsympathetic to identity as politics, as political performance. There’s a place, I think, for strategic essentialism: for the use of identity to create community, to centre sidelined voices, to defend ‘standpoint epistemology’, to bear witness and collate testimony – to redress structural inequity. As a person, a citizen, a comrade, I get it – I can even get with it.

As a writer, I find it profane.

Writers shouldn’t be joiners, shouldn’t be boosters or censors or mouthpieces – representatives – of anything but their own truths. They should protect, at the exact cost of their art, their artistic sovereignty. Because a correct literature is not a moral literature. Because without sovereignty, a writer is an instrument of a foreign power – truly a puppet, lackey, collaborator, quisling – and their work no more art than those millions of forced, falsified autobiographies written by my forebears. As soon as a writer can be said to be what others label them (from whatever intention), they’re no longer – no longer allowed to be – entirely themselves.

‘Entirely himself’. This is how Malouf describes Peter Porter, the Australian-born poet who spent his adult life as an expatriate in London. Belonging neither there nor here, he was instead ‘made’ by books (Auden, Pope, Donne), music (Mozart, Donizetti, Verdi, Bruckner, Bach) and, most of all, language. Malouf has written, of Christina Stead, that she ‘belongs wherever she puts down her intelligence and allows it to take root’. Of Porter again: language is ‘the only place he has ever been at home’. I might be projecting, but it feels to me as though Malouf might be projecting here.

English is my second language, my better language. It’s the language better suited to my way of thinking – which was conditioned by it to think so. (It takes a mongrel, maybe, to know a mongrel . . .) I’ve never felt unwelcomed in it. Which is more than I can say for every place it’s spoken. For me, the question of a writer’s ‘identity’ – if it must matter – is answered, of course, by words. The true pedigree is linguistic. The true passport is imaginative. Writers should get some say in it. (Fancy that!) What matters is not what tribe or place the person was born to but what community the writer has made for themselves through reading, thinking, writing. Malouf’s first name comes not from his Jewish or Melkite Catholic heritage but from Dickens – Copperfield, not King. His work, he wants us to know, is descended not from patchy family history but from the all-access traditions of so-called ‘high art’, and within them the writings of Homer, Hesiod, Horace, Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Balzac, Hugo, Kipling, Lawrence, Kafka, Proust, Mann, Joyce.

There’s a metaphor of Jean Rhys’s I love in which she describes literature as a great lake to be continually fed. You pour yourself in, as a writer, you draw yourself out as deep as you dare. When Malouf praises overlooked Australian writers Kenneth Mackenzie and Frederic Manning by placing them in the company of Mann, Radiguet, Kafka, Musil, Hamsun, Camus and Beckett, it is the opposite of cringe – it is a carriage of justice, an action of equilibrium, of graceful re-centring. It is welcoming them into the middle of the lake, where the water, though darker, runs deepest.

Author Bio

Nam Le is the author of The Boat. He lives in Melbourne, Australia.