In House, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s avant-garde horror comedy film, a young girl called Gorgeous returns home, where her father introduces her to her new stepmother. Upset, the girl runs away to her aunt’s house, inviting six of her friends along. Soon after they arrive, supernatural things start happening: one of the girls’ head is found in a well, another is eaten by a piano, Gorgeous is possessed. Released in 1977, House was panned by critics but won a cult following for its originality, its outrageous cheesiness, and its playful special effects (which were made purposefully to look unrealistic).

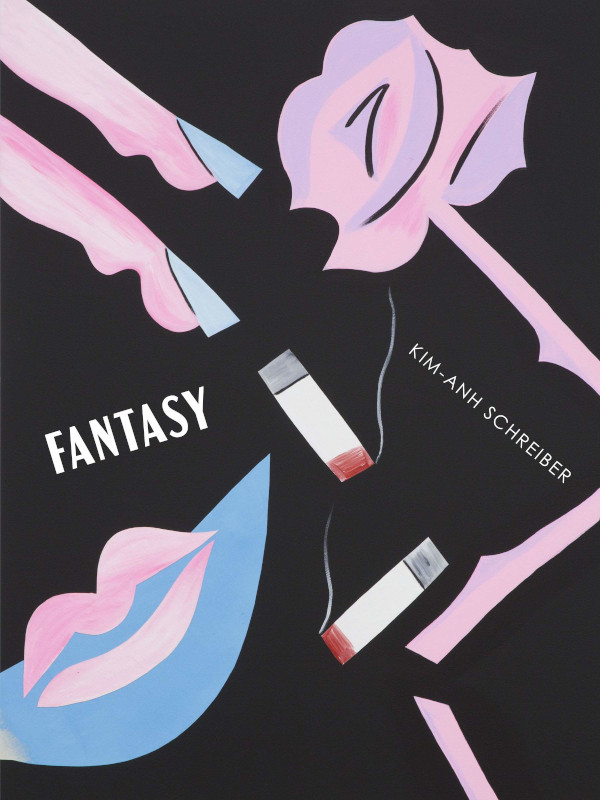

It is this movie that is the frame of Kim-Anh Schreiber’s debut cross-genre novel Fantasy. Indeed, Fantasy is the name of one of the film’s characters, one of Gorgeous’s friends who is the first to notice the strange happenings during the group’s visit. Like House, Fantasy is hard to pin down. While House mixes horror and comedy with a heavy dose of experimentalism, Fantasy mixes film criticism, narrative prose, and (impossible) performance for an equally surprising piece of literature.

It begins with a bicycle accident. While recovering, the narrator’s body begins “to feel things: low levels of all-over pain and panic.” She has trouble describing it until meeting with a chiropractor. There, she learns the extent of the damage: “my body was changed forever…” she says, “I was no longer in charge…” and that “contrary to the idea of my body I previously had, in which it was an ecosystem harmoniously housing a joint, the joint seemed to be destroying the ecosystem.” The image conjured up is one of a body turned in on itself, the person—the body’s soul—trapped inside.

It’s easy to see why the narrator would be attracted to a haunted house movie like House. But in reading the film, the narrator finds a lens with which she can view her life: Obayashi’s cinematic realism. In this kind of realism, it’s not so much about making a film look real—to seduce the viewer into what looks like reality and make her forget that she’s watching a film—as it is about calling attention to the film as a film. Schreiber points to the “camera shaking in the hands of its operator” or “a cut into the film and the collaging of other layers over it.” Obayashi’s realism is an extension of Brecht’s theory of epic theatre but adapted for the cinema. The key for Schreiber and her narrator is that such a theory rejects the idea that postmodern techniques—collaging, discontinuity, metafiction, intertextuality—are unreal or unnatural. Instead, these technique problematizes the “natural,” the “real,” the “continuous,” and the idea of coherence. In such a train of reasoning, the traditional story is an abnormal monster disconnected from lived experience while the postmodern is closer to the disorienting experience of reality.

This, in particular, speaks to the narrator, a biracial woman of German and Vietnamese descent: “I use this concept of realism to understand mine—that feeling of overall continuity despite persistent cultural discontinuity, a mutant feeling that comes from growing up in two families from two different countries with two different wars hovering in the background of our lives in America.” As Schreiber rejects the idea of a coherent familial trajectory, she creates an ontological exploration of biracial identity and experience, taking this to another level by embedding this theoretical framework into the form and structure of her novel—a collage that is less of a linear narrative and more like a constellation.

Readers are presented with fragments of the narrator’s own life via memories and family history: going to a Christian school as “the only one in my class whose parents were not American;” her mother’s family’s exodus from Vietnam by helicopter; memories of writing poems with her Omi, her German grandmother, as well as days spent at her Bà’s home, where she is comforted by the cacophony of relatives. But it’s her parents’ divorce that sticks out the most, and even more than that, her mother’s abandonment of the family and the realization that “whatever, or whoever, [her mother] was, she didn’t seem to want to be there.”

This realization, however, doesn’t make the fact of abandonment less painful. It’s what haunts the narrator so much that, in the third and final section of the book, she dramatizes the mother-daughter relationship through impossible abstractions—talking flowers, disappearing set pieces, movies projected on walls, flooding rooms.

Throughout it all, Schreiber writes with sharp emotional focus. While the pain of abandonment is present, there’s a particularly stinging gap that opens up between the narrator and her Bà after her mother leaves: “[m]y grasp of Vietnamese froze, even declined, and it was harder and harder for Bà and I to get to know one another as we grew older, and I didn’t have the words to say that to her, so I don’t know if she ever understood.” Later, there’s a fear “that one day I would forget that I was Vietnamese.”

Fantasy is a challenging read because it’s a book that evades coherent description—at one end, it’s thoroughly and seriously essayic and at the other, it’s a surreal farce. But that is partly the book’s point: that nothing in one’s story is perfectly graspable, less of all our memories, those building blocks of our narratives. It’s telling that Schreiber opens the book with a look back at one of the narrator’s early memories: that of poring over pictures, brought back from a trip to Vietnam, with her family. While the adults laugh, the young narrator laughs too, but it’s only later in life that she comes to see that she hadn’t understood what was happening at the time. “I didn’t realize, for example,” she tells us, “the significance of that trip” (referring to the opening up of US-Vietnam relations) or “that they couldn’t go back, or that they were living in exile” (because they were refugees who fled a communist regime). There’s a sense that there’s more unknowables to be uncovered with time and wisdom, making memory extremely untrustworthy, as well as the idea that even our memories might be selective at best or completely false at worst: “Maybe I had once made up a fantasy memory, that after a while became a real memory,” Schreiber writes, “That happens a lot. In a way, memory is an evocative curator: Are the individual images all that important, or do they blur into a utopia of the past?”

Fantasy subverts the idea of narrative. At the same time, Schreiber’s subversion is not without emotional heft. There’s a piercing sadness in this work. In the last section, in particular, we see the narrative and the scene of a play falling apart, the book coming to a close as everything that holds it together comes undone.

In the midst of this chaos, the daughter character, an echo of the narrator in previous sections, reflects on her own fear, and since it’s in play script format, the character is forced to say it aloud, to speak it into the universe as a confession: “I feel I am a broken link. I think that one day my children will not speak this language, will not grow up in a house where Vietnamese is so close and ever-present, and if it is preserved at all for the next generation it will be something like a flower pressed into the pages of an old book…”

Fantasy is about what we might have or could have inherited and the specific grief of disinheritance as well as a fear of losing cultural memory and identity. It’s a type of existential horror that Schreiber writes about and, like any horror story, there’s a feeling of dread that what haunts us will continue despite the story’s ending. This is a powerful debut from an author pushing the boundaries of storytelling and mapping new terrain in its art.

Fantasy

by Kim-Anh Schreiber

Sidebrow Books, $18

Contributor’s Bio

Eric Nguyen is the Editor in Chief for diaCRITICS.