Growing up, there were two forms of media I consumed voraciously: one, period dramas from TVB, the Hong Kong-based television broadcasting company whose productions were ubiquitous in Vietnamese households I knew; and two, fantasy novels like Lord of the Rings and His Dark Materials and of course, Harry Potter. I saw half of my world in the first, and the other half in the second. In the miniseries centered on complicated women—women who placated their husbands in the same breath as they commandeered their sprawling households—I saw my grandmother, my mom, my aunts. In tales of adventurers walking through worlds of breathless wonder, I saw me, or at least who I wanted to be. Yet for my entire childhood, the two halves were like me and my reflection in the mirror. They never met.

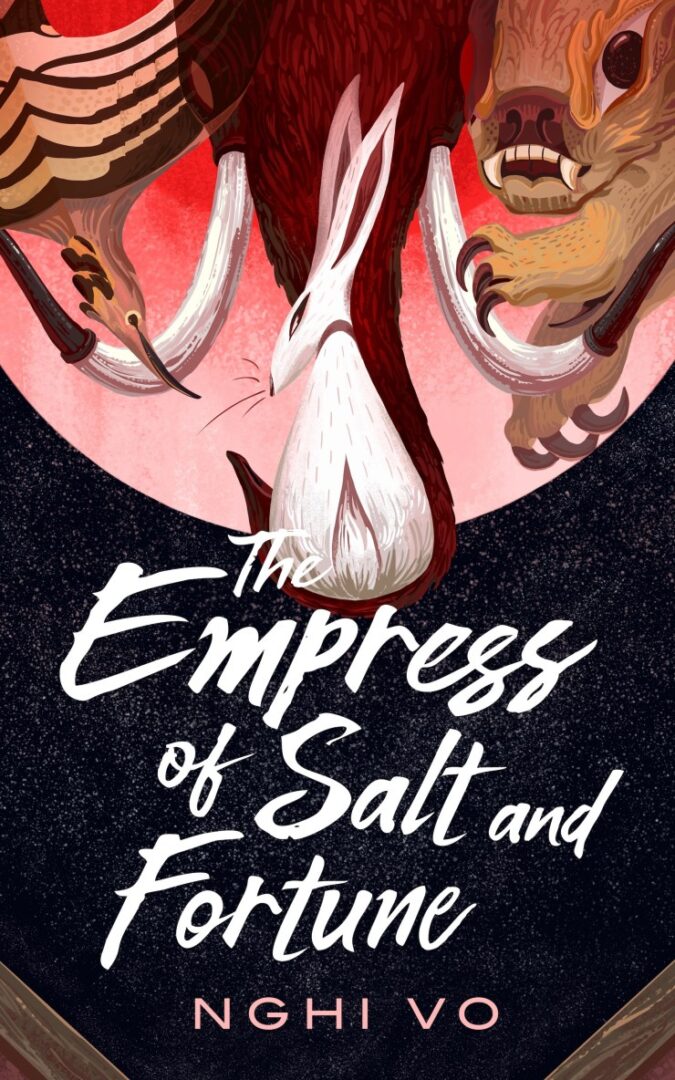

Reading the adult fantasy novella The Empress of Salt and Fortune by Nghi Vo, however, that mirror melted away. The halves met.

This isn’t the first book I’ve read in which that is true. A lot has changed in the fantasy genre since I was a little kid whittling weekends away in a public library. There are now several award-winning writers who draw clear inspiration from East Asian cultures in their epic fantasy novels: Aliette de Bodard, R. F. Kuang, Yoon Ha Lee, to name a few. Still, it never stops delighting me to see an East Asian-inspired fantasy work—especially when it comes in a package as tightly woven as The Empress of Salt and Fortune.

The book is structured as a story within the story (hence the cover copy’s evocation of Margaret Atwood). Chih, a cleric, seeks out an old woman living in seclusion named Rabbit. As Chih records Rabbit’s memoir and takes inventory of the keepsakes Rabbit has collected throughout her life, Rabbit is revealed to have once been the recently-deceased Empress’s closest handmaiden. What unspools then is both a grand tale of an empire’s defeat and a dynasty’s rise, and the deeply personal story of a “side character.”

I put “side character” in quotation marks because it is both true and yet incomplete. In some sense, Rabbit is a side character. It is In-yo, the Empress she serves, who propels all the novella’s forward action. Rabbit is often the audience surrogate through whom we view In-yo. Yet she is also much more to the story. The relationship between In-yo and Rabbit is the novella’s narrative thorough line and emotional core, and brings about its most satisfying pay-off. Without spoiling the story, Vo plays with readers’ expectations of the roles of a “lead character” and a “side character” throughout the novella. Ultimately, she subverts these expectations in delightfully unexpected ways to deliver a fresh and complex feminist message. Let’s just say that Vo is keenly aware that in our world, women’s history and forgotten history have often been synonymous with each other.

Unfortunately, perhaps as a direct consequence of the attention paid to In-yo and Rabbit’s relationship in a breezy 100-page book, other aspects of the story are less successful. Characters beside the two women never fully step off the page. Sukai, another servant of In-yo, is clearly meant to be the novella’s third most important character—he is, in fact, represented on the novel’s cover along with Rabbit and In-Yo—but is as best sketchily characterized. As a consequence, the romance between him and Rabbit, on which significant time is spent, lacks emotional force in and of itself. It becomes affecting only near the novella’s end, when its outcome serves to underscore the tensions and strengths in the women’s intimate relationship.

The worldbuilding is also lackluster and forgettable, which is particularly disappointing for a book in the fantasy genre. Vo’s world is intended to be a diverse one, filled with kingdoms and empires in conflict with each other. Unfortunately, Vo doesn’t give readers enough cultural differentiators for these places, and in the end, they and their populace exist only as names. Though Vo interestingly paints a world in which the border between the human and the fantastical, she populates it with a hodgepodge of familiar but inexplicable references like fox spirit and kirin and giant mammoths. None of this is helped by her cheerful blending of various East Asian cultures throughout the book. To be clear, there’s no inherent issue with utilizing Vietnamese names next to Chinese names, or Japanese mythology next to Chinese mythology. East Asian cultures heavily influence each other, and I’m generally quite happy to give Asian diasporic authors the freedom to draw inspiration from where they’d like; but as an Asian reader, it’s a little discombobulating to see the seams where Vo has mixed the cultures, especially when the actual elements inspired by real cultures are presented so roughly and without any apparent pattern.

More damning still, the fantasy elements of the story disappear for whole chunks of the narrative at a time. This is a political drama set in a magical world, and so I was excited to see how Vo might weave magic into the plot. Yet magic has little consequence on the political machinations. To be frank, the magical system barely exists. It primarily consists of occasional references to battle mages and weather mages, both of which lack weight and specificity.

In fact, strip away all the fantasy from the book, and one would actually be left with its best parts. At heart, this is two women’s story of tragedy, kinship, and duty.

Still, despite these flaws, The Empress of Salt and Fortune is worth the time of fantasy fans, especially those who preference characterization. Though I comment on the thinness of certain story elements above, the reading experience itself is incredibly pleasant. Vo’s sparse but evocative writing style accentuates her story well, and she has an ethnographer’s eye. I only minded the weak worldbuilding when I took my attention away the details about her characters that Vo relays so precisely. Even now, In-yo’s ink black hair and Chih’s scooped handfuls of food linger in my mind.

The book’s ending practically announces that a much longer sequel is coming. If that work can marry the strengths of this one with much stronger world mythology, then Asian-inspired fantasy has a bright new star. Whether or not that follow-up does, however, the moody Empress of Salt and Fortune is worth an afternoon of your time.

The Empress of Salt and Fortune

by Nghi Vo

Tor.com, $12.99

Contributor’s Bio

Nhu Le is an emerging writer from Boston. During the day, she’s a young professional in the social sector. At night, she wanders the hidden alleys of genre fiction.