Jess Boyd sits down with Doris Hồ-Kane, chef, founder, historian and archivist, to discuss her new bakery initiative, Bạn Bè, and the ways that it is nourishing a nation of people hungry for sweetness and a taste of home.

Inspired by Ocean’s Vuong’s letter to his mother in the New York Times, this is for mẹ lives online as a borderless mailbox for Asian identified people to share stories rooted in mothers, motherhood, motherlands, mother-tongues and family.

Con Ăn Bạn Bè Chưa?

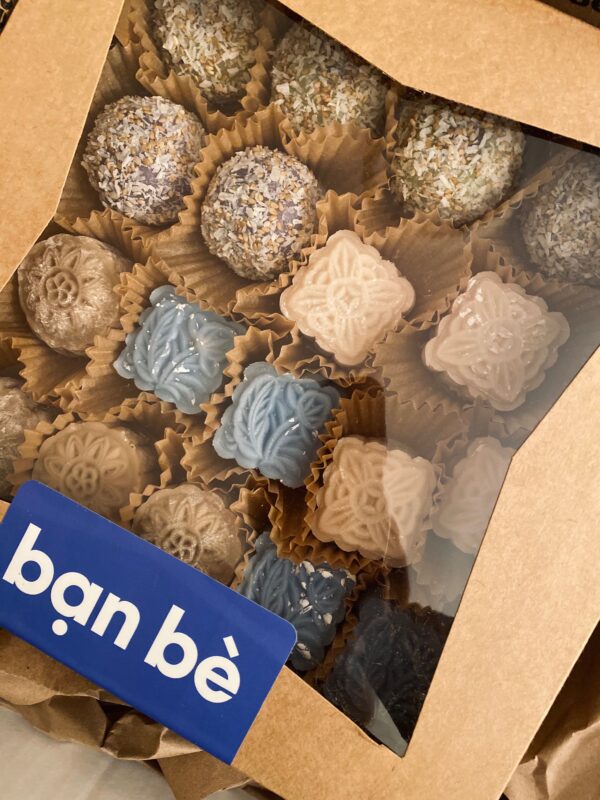

To ask your child “con ăn cơm chưa?” is to tell them you love them. Doris Hồ-Kane’s new bakery initiative, Bạn Bè, has become an edible love letter to the diaspora in a time of crisis. With her Vietnamese inspired butter cookies, Doris ensures that we are well fed and well loved.

Dr. Gary Chapman rolled out the idea of five love languages, the idea being that individuals resonate with one language more than the others. In the Vietnamese culture, the sixth and most important love language is food. This sixth love language is an edible, indelible expression of emotion that can transcend generations, trauma and words left unspoken. Bạn Bè adopts this love language as its mother tongue, drawing on ancestral resilience and nostalgic recipes to nourish and nurture a nation that is hungry for change.

Bạn Bè was initially destined to be a brick and mortar bakery in New York, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic and issues with the space, Doris created an online home for her diasporic desserts.

Food is political and personal, evoking nostalgic memories of dishes prepared by loving hands. It is both important and powerful to see the foods we grew up with in public spaces. In naming her bakery and cookies using Vietnamese words and diacritics, Bạn Bè reverberates with ancestral echoes.

Bạn Bè currently offers butter cookies in the following flavours:

- Coconut pandan

- Black sesame ube

- Tamarind cacao nib

- Cà phê crunch

The flavour foundation and packaging aesthetic was inspired by blue tin butter cookies, the empty tins of which filled many Vietnamese homes, often finding new life as homes for sewing materials, loose odds and ends, leftover food, and anything else that bà, ông, mà or ba needed to store safely.

What inspired you to name your bakery Bạn Bè?

Bạn Bè is an homage to friendships, my family who are my best friends, my community, and my future pals I’ll make along the way as I continue to spread Việt love by way of not-too-sweet sweets here in New York City, and beyond. Desserts and friendships have always gone hand-in-hand throughout my life. There is nothing more comforting than a steaming bowl of chè xôi nước that my mom would ladle into chén cơm whenever I was in a foul mood. One of my best friends in high school would bake oatmeal chocolate chip cookies for every occasion—my birthday, the night before starting a new mall job, the day of a big math exam—whatever, whenever! She would excessively Saran Wrap them to sleep on plates from the thrift store. To this day, I still think they’re the best cookies I’ve ever had. (The recipe was from the lid of a Quaker Oats canister.) In college, there was a music venue inside an old cement factory called Rubber Gloves where we’d all hang out. Melt-Banana, Wesley Willis, Animal Collective, The Get-Up Kids, and Cursive would regularly come through. My best friend at the time would doggy bag slices of the most Thiebaud-esque vegan strawberry layer cakes from her part-time café job. By the time we got home, we’d reek of everyone else’s cigarette smoke, but the cake perfumed our dreams as we fell asleep two hours before we’d have to wake up for drawing class. I am shaped by friends and family who accepted me, challenged me, and supported me. I want to make 18k gold (because anything less is unacceptable to Việt aunties) and brass Bạn Bè necklaces; bạn on one piece, bè on the other. Bạn Bèsties.

Which Vietnamese women most inspire you when you are creating for Bạn Bè?

There are countless Vietnamese women that I admire. Their collective grit and resilience; their stories; their voices—light the path forward. My mom and sisters are my past, present, and future. Taking it all the way back to 40 and 248 A.D., I’ve dreamt about wrapping up fragrant banana leaf sachets of xôi dầu phộng for Hai Bà Trưng or Bà Triệu before they headed off into battle. Or making jackfruit thach rau câu submerged in rich coconut cream for the scandalous poet Hồ Xuân Hương as she wrote in Chữ Nôm. I would have loved to sit with both of my grandmothers when they were younger, wrapping up bánh tét in Nha Trang and Quy Nhơn. Bánh tieu lá dứa for the majestic filmmaker and writer Trinh T. Minh-ha. And Ali Wong, of course. One of her fears is that her mom’s Bánh Bớt Lọt lady would pass away, because she’d never get to experience that caliber of bánh in America again. I would love to be her bánh ngọt go-to. No landline, but my DMs are always open!

When you are baking, your hands are covered in traditional ingredients like pandan and black sesame. At times, does this feel like an immersive way to commune with your ancestors?

Absolutely. I get emotional every time I bake or make these desserts. I sometimes worry that my new way of approaching these tried-and-true desserts would elicit side-eyed disapproval from our ancestor aunties. The earthy smell of steaming đậu xanh, the grassy sapor of lá dứa, the bounce of thàch before it quietly shatters against your teeth, and the swirly patterns of oil in rivers of coconut cream always lead me back home to a place I’ve never lived—quê hương ơi.

How do you choose which ingredients to use and how to combine these flavours from multiple homelands?

I usually use what’s available to me. That’s how Bà Ngoại and Mẹ roll. The combinations I come up with are from childhood dreams and memories. One combo that is very specific to my Bà Ngoại is icy watermelon on hot jasmine rice. I cannot wait until summertime to share my take on that one! The very popular bơ cookie tins come from the same headspace. I wanted to do a playful take on those iconic buttery Danish cookies. The blue tins were, and still are, universal in most immigrant-refugee homes, but I needed to obliterate all of our engrained generational trauma in a fun way, for my own sake. It has been so therapeutic and carthartic baking up these tins. It’s a good thing because I have about 3,000 tins (and counting) to go! I hope some of that healing, that intention, comes through in my food.

What does food as an avenue for activism look and feel like to you?

This defiant opposition looks beautifully messy, feels incredibly rewarding, and smells like pandan-infused palm syrup coming to a slow, rolling boil. I would consider myself a life-long activist. First, as a teenaged women’s rights, anti-racist, and animal rights activist in the late 90s-early 00s. When I moved to NYC in 2001 for art school, my activism was engrained in my design work. I’m the founder, historian, and archivist of 17.21 WOMEN, where I have been working to decenter and refocus historical narratives by creating an alternative archive. Now that I’m working with food, I’ve channeled some of that energy here. Food is inherently political. Việt desserts are so rare here in New York City, and I feel that their presence alone is powerfully subversive and so deliciously potent.

Which Vietnamese dessert would you make to tell someone that you loved them?

Chè Bà Ba is it. We should just go ahead and crown her hoàng hậu. Warm, rich, deep, hearty, and so, so dai—those perky little mochi balls swimming in a pool of coconut milk. It’s actually pretty sexy. Haha. What would Bà Ba think?! Vietnamese dessert soup for the soul. I like to describe all of our Việt soups, savory or sweet, as a warm ôm in a bowl.

When you were growing up, what did your loved ones fill empty cookie tins with?

Bà Ngoại would fill her tins with cạo gió coins and small bottles filled with pretty oils and spicy ointments. Tiger Balm wasn’t as popular in our home—Eagle Brand Medicated Oil or a dầu xanh dupe would be the aches ‘n pains weapon of choice for my grandmother. We called it Buddha Oil since it was packaged in a vessel shaped in the likeness of Laughing Buddha. Whenever we had a stomachache, Bà would lift up our shirts and dab a small amount in our belly buttons. Worked like a charm every fucking time! She also had another tin, a red limited edition holiday one, filled with plastic vials of perfume and glass bottles of nail polish. My mom would fill hers with sewing notions. For the earlier part of my childhood, my mom was an at-home piecemeal seamstress. Sometimes, to our delight, there would be random hard candies like Brach’s butterscotch or cinnamon discs and sticks of Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit Gum stashed in there.

Filling a home with cultural sounds, scents and sights is powerful medicine to raise children around. What are the sounds, scents and sights that you want your children to remember being surrounded by?

Sounds: Tiếng Việt, renditions of Kìa Con Bướm Vàng, pirated copies of Paris By Night, Mẹ’s humming, Bà Ngoại’s laughter, storytelling

Scents: Incense burning during đám giỗ, Việt food and desserts, boiled lotus seeds, ngò ôm, dầu xanh, salt water

Sights: The faces of our ancestors, family, diacritics, golden, brown skin, phở and bún for breakfast, bánh mì dipped in condensed milk, diluted with hot water

What is your favourite Vietnamese ingredient to cook with and why?

It changes every week, but right now, I’ve been experimenting with rau câu and glutinous rice flour. I love the contrasting consistencies of both—perfectly giòn and satisfyingly dai.

What music should we listen to as we eat Bạn Bè?

One should listen to Khánh Ly, CBC Band, Tiny Yong, and Emily’s Sassy Lime on repeat. Ad infinitum.

What food most reminds you of home?

BBQ and gỏi đu đủ. I’m from Texas! On weekends, we would have everyone in our extended family over for barbecues in the backyard. My mom would have us sit on chiếus and pluck and sort herbs for the gởi. My older sister would be bestowed the honor of kitchen scissor duty to cut the thịt bo khô into julienned strips. Whenever I catch a whiff of BBQ, I am swept away on a bed of fried okra and sweet pickles, transported back in time. Ba wiping sweat from his brow with an old handkerchief, as he made sure everyone was eating more than their share. He would only sit down to eat once everyone was finished. I’ve been vegetarian and vegan for 22 years now, but a lot of my Việt food memories are rooted in the amalgamation of heavy Texan meat culture and the lightness of our native herbs against nước mắm-laden dishes.

What food do you make when you feel homesick?

It’s a really simple dish that I like to eat solo and in complete silence. Canh mồng tơi with soft tofu, cilantro, scallions, and tons of black pepper over jasmine rice. I crack open a jar of chao, scoop out a cube, and let it sit whole on the side of the bowl. Eventually, it slides down and dissolves into the hot soup and the broth gets incredibly salty and pungent. I make sure I drink it all down. It’s life-giving.

What is next for Bạn Bè?

I have been actively looking at spaces that can also incorporate an archive and non-circulating library for 17.21 WOMEN. While we are still experiencing the weight and devastation of the pandemic, I would love to have a private baking studio for pick-ups and a small archive space in-one. Someplace in Brooklyn where I can get through the never ending bơ cookie tin waitlist, and work on finessing my desserts through messy, experimental R&D, while cultivating a catalogue of archive material so rich and mind-blowing that everyone and their Mẹs will finally recognize, amplify, and celebrate our history. We can continue to recover and heal. To immerse myself in our collective stories and our cosmic food culture— to ultimately foster positive change—is my dream.

Interviewee Bio

Doris Hồ-Kane is a proud daughter of refugees; boat people. She was born in Texas but considers herself a New Yorker having lived in New York City for almost 20 years. She is the owner and baker behind Bạn Bè, NYC’s first Vietnamese American bakery, as well as a historian, archivist, and the founder of 17.21 WOMEN, an online archive of Asian Pacific Islander trailblazers whose legacies have been buried by hegemonic historical narratives. A forthcoming book of her 17.21 WOMEN research will be published by Penguin Books in 2022. Before focusing on baking and archiving, she spent over a decade in the fashion industry as an apparel designer, buyer, creative consultant, and stylist. Doris currently lives in Brooklyn with her husband and three kids.

Doris Hồ-Kane is a proud daughter of refugees; boat people. She was born in Texas but considers herself a New Yorker having lived in New York City for almost 20 years. She is the owner and baker behind Bạn Bè, NYC’s first Vietnamese American bakery, as well as a historian, archivist, and the founder of 17.21 WOMEN, an online archive of Asian Pacific Islander trailblazers whose legacies have been buried by hegemonic historical narratives. A forthcoming book of her 17.21 WOMEN research will be published by Penguin Books in 2022. Before focusing on baking and archiving, she spent over a decade in the fashion industry as an apparel designer, buyer, creative consultant, and stylist. Doris currently lives in Brooklyn with her husband and three kids.