I Am Not a Spy is a claustrophobic performance. The audience is locked out of the gallery but can watch her either through the windows onto the street or on CCTV writing ‘I am not a spy’ on the black surfaces of the art space hundreds of times in chalk and white paint. The performance is nearly three hours in length.

Those who gathered early along the sidewalk in front of the gallery are met with a sign propped up against the door which reads:

Do not proceed beyond this point

the subject is being detained and

surveilled.

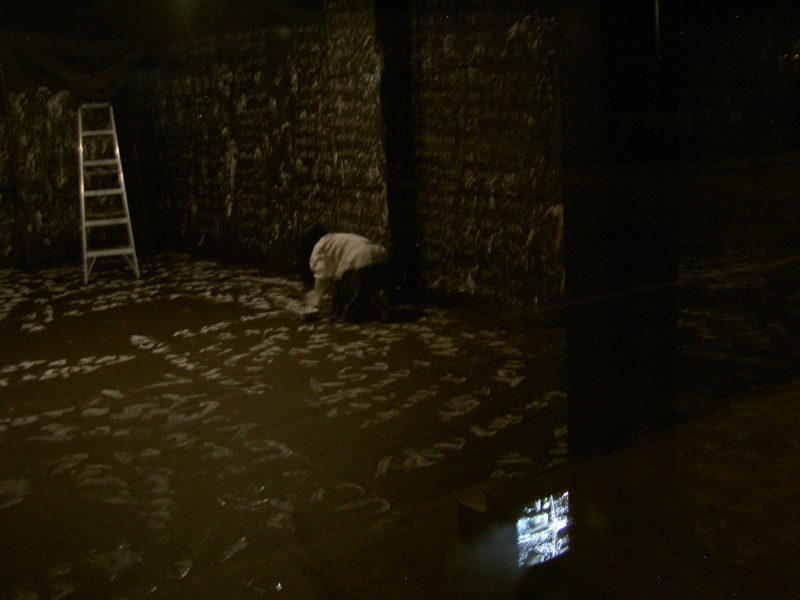

Behind this warning was a door with a large glass pane which otherwise would have led into the gallery. Instead there was an old-fashioned television monitor displaying four nearly simultaneous channels of night vision footage of Quynh Lam inside the gallery in real time. She sits in the middle of the room. All of the surfaces are entirely black, lit by ceiling-mounted bulbs, unshielded and unfiltered. There is a ladder in one corner. She stands and moves about the room. She searches the space. She feels the walls, the corners, looking for egress. It’s a pantomime of imprisonment.

Lam, who was living in Tennessee at the time, was visiting Boston and stayed at the home of a friend of a friend. Inexplicably, her Boston host accused her of being a spy over the course of three days. On the morning of the third day she awoke and found herself locked in her room. For more than 12 hours she remained locked in. She wrote 44 pages longhand in a notebook she found there. She wrote out a sort of self-defense against his charges, but more importantly it was a record of her existence in Boston, at this house, for a specific duration. She would eventually be let out, though not by her host, but by his friend who, for his own reasons—among them presumably deflecting attention away from her host’s erratic and disturbing behavior—tried his best to pretend nothing strange or worrisome had indeed occurred. She politely excused herself as soon as she could. She spent the rest of her trip staying with friends in another part of the city before returning to Tennessee.

Given the backstory, this preamble provides a feminist interpretation ready to hand. After all, it was a man who felt entitled to incessantly question her, refuse to accept her answers, and subsequently confine her to her quarters without consent. In the work Quynh Lam externalizes the part of the ordeal she had the power to control during her confinement: writing the account of herself in the notebook she found in the room. And like so many woman artists, Quynh Lam, as performer, is playing the part of a woman hemmed in and forced to justify herself, absent any grounds for suspicion, and reassure her captor. This theme is indeed present and underscores without dominating the personal contingencies intrinsic to I Am Not a Spy; for Quynh is the woman who was actually locked in an unfamiliar room by a particular man she believed to be a friend. Orthogonal to the issues of gender are the complicated dynamics of nationality and ethnicity. Her host, an American, was also a first-generation son of Vietnamese immigrants. One wonders to what extent Lam’s identity as a Vietnamese woman in America might have played in her host’s accusation. Postwar residual intra-ethnic suspicions? Inter-cultural misalignment? Some of both, perhaps, as well as whatever personal troubles intensified these signals to a paranoiac pitch.

After a few minutes she walks to the back wall opposite the street-facing windows. There she writes in large chalk letters ‘I am not a spy’ for the first time. She repeats this on the same wall, spreading out from this initial proclamation like so many eddies and vortices spinning out from a churning whirlpool. This is all happening in the left hand frame while in the right time is sped up and we see a blank wall and slight shadows flicker across it.

She moves to the side wall to her left. She writes her protest here as a child does when their punishment is to write a sentence out 100 or 1,000 times declaring their intent to not do something again. The lines are stacked with the same indentation, the same font size, the same length across the wall. It’s unnerving to watch. Punishment as penance. Penance for what though, we might ask. However, it is emphatically not penance, for she’s done nothing wrong. It’s an inversion of penance. The child, as it were, is protesting the punishment, defying its purpose by appropriating its means. Quynh Lam, however, is no child. The child is an absence made salient through Quynh Lam’s choice of expression. She is exploring the concept as she explores each new surface.

She finds a paintbrush and a small can of white paint. She sits near the center of the room and paints in large letters an undulating version of the sentence this time. She paints around the spot on the floor until the next open stretch of unpainted ground exceeds her reach. She hops over the drying letters and seeks another location on the ground. In this manner she covers most of the floor in an hour. Some of the lines evoke graffiti, some protest signs.

As the sentences accumulate, on the walls and across the floor, there are variations—of the letters’ height, of length, of shape, and of weight—giving one the impression of her modulated voice. Screaming. Pleading. Imploring. Defying.

She goes back to the side wall, but at its far end, away from the stack of sentences. From the third camera she is shown in profile, parallel to the wall. She appears to be reading the sentences there, thinking. A few quick gestures. It’s difficult to tell from any of the cameras whether she has anything in her hand. She gets closer. She’s smearing some of the sentences in chalk, marring the walls. Her hands smudge swaths through the sentential strata, unable to resist the artistic impetus to raise up and then cancel and yet preserve in turn, aufheben as Hegel would say.

As the video concludes, first in the left hand frame followed by the right, Quynh Lam slows, sits, and then slumps to the ground, surrounded on all sides by the swirling trails of her declarations. Reductio ad lassitudenum. In many ways, this is the aim of interrogation, even of incarceration: to subvert the will of the individual to the coercive power. And of necessity such ordeals vitiate the victim. But Quynh Lam’s audience is certain her exhaustion is temporary—a rest in order to gather again her resilience and begin anew. Scrawled across every surface of her cell is a testament to this, the dignity of an unyielding spirit. It’s not difficult to imagine her performance recast as a parable by Kafka, where a young woman awakens in a claustrophobic room whose every surface is black, locked from the outside by some nameless, faceless power, and provided with only a piece of chalk and a can of white paint. Kafka’s would-be protagonist knows well what the implements for inscription prescribe and portend. Like Kafka’s K, she perseveres and wends her own way through a surreal experience which in her case, by contrast, was only all too real.

Let us not forget the inciting event. A woman, far from where she resides, and even further from home, trusted an acquaintance to be decent—not exceptional, not a moral saint; and a host, who ought to make his home comfortable and safe for his guest, instead locked her in the bedroom she was in for almost an entire day. She staved off panic and fright and worry by writing forty-four pages longhand in a spiral notebook she found on a shelf. We should not conclude that all was well that ended well; nor that at least Quynh Lam was able to sublimate a harrowing ordeal into art. No one should have to suffer such indignities—not for art, not for anecdotes, not for knowledge.

——

I Am Not a Spy (Gallery 1010, Knoxville, Tennessee, 2019), as well as her recent video work of the same name, derived from the CCTV night vision footage she shot on four surveillance cameras at the time. The latter work, a single channel edit of the raw video into side-by-side frames, was featured in a show, “Unlearning”, at Richard Koh Fine Art, Singapore, October 2020.

Nathan Robert Cox is a professor of philosophy at Pellissippi State in Knoxville, Tennessee, USA. His specialty is early modern philosophy, especially the work of Descartes, Spinoza, and Hume, and their respective theories of substance. His teaching and research also include meta-ethics, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of language. He is also a poet with several poems pending publication.

Nathan Robert Cox is a professor of philosophy at Pellissippi State in Knoxville, Tennessee, USA. His specialty is early modern philosophy, especially the work of Descartes, Spinoza, and Hume, and their respective theories of substance. His teaching and research also include meta-ethics, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of language. He is also a poet with several poems pending publication.