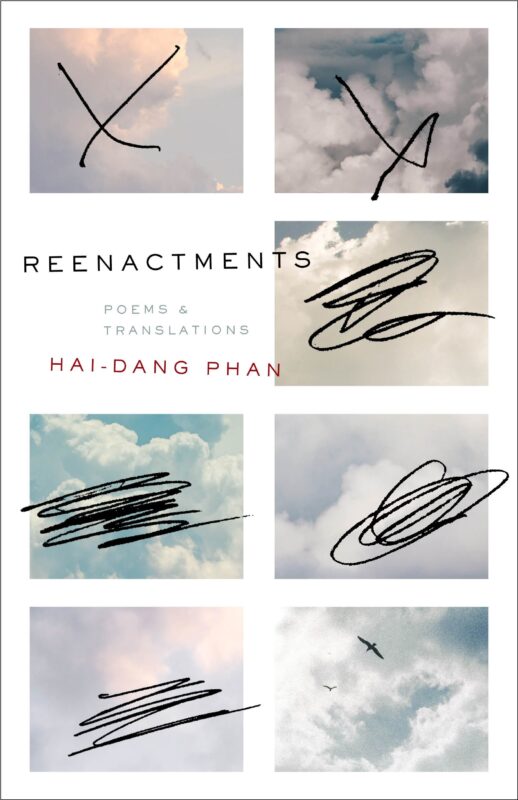

What makes us constantly reenact our lives? What makes us reenact other people’s lives, or lives which never happened, or lives which we barely understand? Hai-Dang Phan’s debut poetry collection Reenactments represents the attempt of not so much answering these tremendous questions, as of asking them again and again in different ways.

Phan embraces how each reenactment renders us ever more distant from the event itself: from the American South’s reenactment of the Vietnam War, to Vietnamese American photographer An-My Lê’s reproduction of these scenes, and then to Phan’s ekphrastic reenactment of Lê’s photographs. A traumatic image devolves into a spectacle, but equally, a spectacle becomes a traumatic site of its own. Distance, then, provides its own kind of intimacy. The opening poem, “Small Wars,” titled after An-My Lê’s 2014 photo-monograph, adopts Lê’s perspective as she participates in these reenactments:

It was my turn to play dead, so I zipped up my flight suit

and monkeyed into the cockpit.

[. . . ]

A giant cicada singed the air with its emergency song, too late too late.

When I came to, the stars in my jungle burned like sodium flares

What begins as a bemused reproach of grown men childishly playing soldier ends with the horrific awareness that wars are waged in the same childish manner, for the same childish reasons. The speaker’s panic that it is too late for her to escape the cockpit of this reenactment is perhaps the result of her failure to realize that she has always already been too late to the Vietnam War, too late to know anything of the war outside from its reenactments.

Phan says in an interview:

I think there’s always been this sense of belatedness for me, of being secondary and “after” in the temporal sense, with all the attendant feelings of insignificance and lateness involved. Writing poetry converts this secondariness into a pursuit.

Phan’s poetry exemplify what Marianne Hirsch terms “postmemory,” which describes the 2nd generation’s fraught inheritance of their parents’ trauma. The generation of survivors are directly linked to their trauma via memory, but the generation after are paradoxically bound to this trauma through its absence, which manifests itself through the silence of those who know, the incomprehension of those who do not know, and the too-human reenactments of both.

In “Spring Offensive,” a poem as clever as it is heartbreaking, the speaker’s mother reenacts the war through gardening:

It was time for an escalation.

The moles were brazen that year.

So my mother with a shovel for a spear

leveled their blind incursions

The moles, which literalize enemy spies as well as the NVA soldiers of the Cu Chi Tunnels, end up drowning after the mother obstructs their tunnels—even suburbia is militarized through this repetition compulsion.

Phan, however, is not interested in simply pathologizing his parents; nor does he pretend that he can be an adequate storyteller of their pasts. Rather, Phan lingers within the liminality of reenactments, not just as an imperfect portal into history, but as a mysterious realm in its own right. The speaker of Phan’s poems does not always know the significance of what he is looking at, but understands nevertheless that he must look carefully. In “Lunar New Year in Orlando,” the speaker feels alienated by the “festive militaria” and the throng of Vietnamese veterans and their families. But then he notices his father observing a patrol boat:

Soon after, I spot you by the Swift Boat,

a PCF-171 propped up on stilts,

stranded on the grass like a desolate shipwreck,

the first one you’ve seen since the war,

[. . . ]

You pat its side like an aluminum horse,

gunmetal skin reflecting nothing,

and look at me with an expression

that could have been a smile.

The image reminds me of my own father. The speaker sees only a “desolate shipwreck,” while his father approaches the boat with a seeming affection, as if it were something alive. However, the boat “[reflects] nothing,” as does his father’s expression. The speaker is confronted with only contours and shadows, while the thing itself remains concealed. But his father, it seems, also leads a life of reenactments, his relationship to the past perhaps also marked by a traumatic incomprehension. In the final lines, both father and son attempt to glean through these reenactments for some epiphany:

picking through the rubbishy aftermath,

watching for the real gator

in his fake pond.

Reenactment shows how we live in the present by living outside of it, and we live as ourselves by imaginatively living outside of ourselves. Returning to my original question, then, we might venture one answer through a similar reversal: what makes us reenact is the fact that each reenactment is the making and remaking of ourselves. Phan’s delineation of our cultural reenactments are numerous, ranging from Google Earth and a punk rock band named Viet Cong to the video recording of a soldier’s death and the Syrian refugee crisis. While some reenactments are dark, others are wonderful, such as the strange inclusion of his translations of Vietnamese poems alongside his own. The ethos of Phan’s collection is emblematized through these translations: each reenactment becomes an act unto itself, multiplying and fracturing notions of a holistic past or original event. Through each poem, a birth, and with each page, the world shifts ever so slightly.

Reenactments

by Hai-Dang Phan

Sarabande Books, $15.95

Contributor’s Bio

Sydney To is an English PhD candidate at UC Berkeley, with research interests in Asian American literature, transpacific Vietnamese literature, critical refugee studies, and biopolitics. His work has appeared in Asian American Literature: An Encyclopedia for Studies and Asian Review of Books.