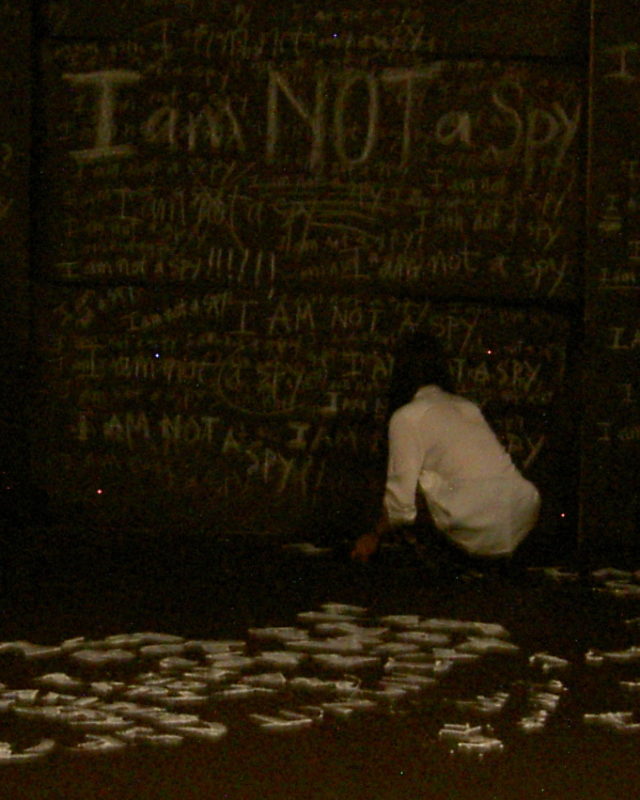

Quynh Lam’s exhibition, “I Am Not a Spy”, is a presentation of surveillance and sublimation. The surveillance is obvious. The original performance was recorded on four night-vision CCTV surveillance cameras, each recording appearing simultaneously in a separate quadrant of a single channel for the audience to watch on a monitor, while locked out of the gallery, in addition to their being able to peer through the gallery’s street-side windows. Each of the cameras was placed in different corners, exacerbating the dread of the ubiquitous panopticon. Quynh Lam performs in the video as “a prisoner of her own”. We do not see anyone lock her in or stand guard. She searches the room briefly, feeling its black walls and searching for seams. She moves to the back wall, opposite the audience on the street, and writes “I am not a spy” across it. We, too, are now apprised of the charge against her and are witness to her sublimating defiance. She writes this sentence—sometimes in chalk, sometimes in paint—hundreds and hundreds of times on every available surface. Yet she is in charge, despite the repetition and ensuing tediousness. Close to the end, she starts to smear hand-size smudges through whole swaths of sentences, as if saying that even her means of subverting her imprisonment cannot be co-opted by her captor: Watch me as I erase my testimony. The video concludes with her stopping and slouching, surrounded on all sides by the same sentence in white letters against an abyss of unyielding blackness, and then slumping to the ground exhausted. She lies down in each of the quadrants in turn, only seconds apart. She has edited the raw, four-channel footage (3-hour duration) into a new shorter version (4 minutes 44 seconds), also titled “I Am Not a Spy”, and it is currently part of a show, Unlearning, at Richard Koh Fine Art in Singapore.

Nathan Cox: Could you share the context of the performance? What led you to make this piece?

Quynh Lam: The inception of this piece was a traumatic experience I had when visiting Boston in March of 2019. I stayed at an acquaintance’s apartment while in the city. He asked if I was a spy shortly after I arrived at his apartment. I first thought that was a joke since I usually ask Vietnamese people in the U.S how can they get here and when did they settle down in the U.S – just my curiousity- however, he later also asked to check my suitcase to see if there was a tracking device. His questions then turned into accusations, and at the end of the day, I found that the door to the room in which I was staying had been locked from the outside. For almost a full day I was locked in there. At some point, I found a notebook and began to write, until the door was finally opened, not by my host but by his friend, whereupon I destroyed the notebook—all forty-four pages I had written during the confinement—and left the room to find a way out of the situation entirely. At around 5 a.m., I sneaked out the house with my suitcase and crossed the city. I knew a professor at Mass Art and, when I arrived, she graciously offered to stay with her for the rest of the week. Even though I thought of her home as a shelter, it still took some time before I was no longer in a panic. I didn’t want to talk to anyone.

After I returned to Knoxville, I thought I was depressed. I remember that was the first week of April and I had a studio visit with Tommy Kha, a Yale alumnus artist. I told him about this story and we talked about Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s story “The Yellow Wallpaper”, the imagery of a woman scratching the walls, and her depression. In response, I empathized with the narrator, in that I, too, kept writing when it seemed most hopeless while locked in the room, and Kha said, “Why don’t you make a performance?”. That was all he said and his words follow me until September—half a year after the incident. Once I had enough distance from the event, I began to conceptualize the piece, figuring out how to layer them together, as it were, and setting up this performance just as I wanted it to be.

What did you write in that notebook and why? How does the notebook figure in either version of “I Am Not a Spy”?

I was probably not thinking very clearly and didn’t really know what to do. I thought about calling 911, but I kept wondering if my host was outside and heard me call. I knew he was gone, yet I couldn’t help worrying about him still being there. I was so scared and didn’t know what my fate would be at that time, so I chose to write in a notebook I found in the room and tell my story, in case anything happened to me and someone could read it later. I wrote out facts about my life and all the reasons it was ridiculous

As I mentioned, I did destroy the notebook. I scratched out the text and tore out whole pages. I remember thinking that this was like how a spy records their voice, like a report or diary for every day undercover performing their duties. I found the ironies here appealing, as an artist, though not as a human being. I am not a spy and never have been, but on that day because he had locked me in and feeling as I did—scared, panicked, uncertain—I had to resort to behaving like a spy. I used my cellphone to take pictures of all of his books on the walls. Some of these concerned psychology and psychiatry; some looked like research into Southeast Asian politics.

NC: Certainly, this was a very personal experience for you. However, in the performance you have abstracted away almost all the remnants of it as being specifically about you; instead you present yourself as an anonymous prisoner. The audience was not given any context beyond the sign outside of the gallery which read: “Do not proceed beyond this point the subject is being detained and surveilled”. There appear to be broader themes of surveillance, self-punishment, and feminism at play in this work. Were any of these themes present when you conceived of the performance? Did you think of it as a way of dealing with what happened?

QL: Those themes are present, to be sure. But I usually feel my way to the themes of my work, rather than have them in mind as I imagine the performance. Does that make sense? I guess what I mean is that when I feel I have a good premise for an artwork I trust that there must be more general themes lurking somewhere about, but it is only when a work is quite far along that I think of the thematic elements. The reason I cut away so much of what was personal has more to do with my art practice as a whole. For me, my art is always a kind of tension between the personal and the universal, like that between memory and history. Also, I am more concerned with the art in the performance than in documenting my unfortunate experience.

Further, the art is as much for the audience as it is for me, in that I alone do not get to decide what my art means. To give one example, a member of the audience spoke to me afterwards and said that she thought I was reenacting a story of a female Chinese prisoner. She told me that when she was watching outside the gallery, without knowing the context, the white text I wrote in the wall—like a thin line scribbled continuously—reminded her the woman in prison in China using her voice to sing, connecting to other prisoners through the darkness of the prison. I love how meaning works; in this case I had no idea about that story but for her there was a connection. It all comes from the audience members and their knowledge and backgrounds.

As to whether I used the piece to process or deal with the experience, not really. My art is not therapy as such. The trauma was over and whatever processing of it that was necessary had already taken place long before I commenced “I Am Not a Spy”.

And if it makes a feminist statement of some sort, I’m happy about that, but I did not set out to do that. I am a feminist, so it is not surprising to me that my performance could be interpreted in that way.

NC: The American author Thomas Pynchon has a persistent theme throughout many of his novels, that of sado-anarchism. A simplified summary of it is that in our modern—if not post-modern—lives we are increasingly at the mercy of systems we do not understand, perhaps even some we cannot understand, and which exert enormous influence on us, for example, governmental bureaucracies, multi-national corporations, or the internet. Where their power begins or ends is always mysterious, so these systems tend to instill paranoia and distrust amongst us. Pynchon’s fiction suggests that we are left with a terrible dilemma: either acquiesce to those systems or pre-emptively punish ourselves and, paradoxically, evade their logic of punishment for transgression, and as a result perversely undermine their power. In “I Am Not a Spy”, repeatedly writing the same sentence could both be seen as a punishment and as defiance. Writing sentences over and over is often a punishment for naughty children; yet your sentence includes the crucial ‘not’, thereby negating the content of the punishment while preserving the form, and as such a provocative affront to authority. But you have, as it were, given yourself the sentence in several senses. Did you intend this piece to interrogate the dialectic of power, self, and punishment?

QL: Echoes of Foucault, yes. I had a charming conversation with Dr. Rachel May Golden, an associate Professor of Musicology (Historical Musicology & Ethnomusicology) about Foucault after my performance last year as well. I was thinking about his ideas of discipline and punishment, as well as the fears of panoptical surveillance. I think Foucault was interested in sado-masochism himself, both personally and professionally. That’s interesting now that I consider it, though I cannot say that it was conscious at the time. I haven’t read any Pynchon, but it is a fascinating notion. After the event, back in Tennessee, I wrote a lot about what happened, mainly notes to myself. It’s important to emphasize that I didn’t understand what happened to me in the least, not at first. It was such a confusing episode that I had to dwell on it for quite some time before I could make any sense of it. So, it is a kind of self-punishment (at least it feels like it sometimes) and at the same time it is liberating. All of us repeat certain patterns in order to make sense of our world and ourselves. Perhaps there’s also some feminism here as well. As women, we find ourselves repeatedly telling others the same thing, time after time, always having to re-affirm who we are. Pynchon’s dilemma, as you put, may have a special resonance for women.

NC: How long has performance art been part of your artist practice?

QL: My first solo performance was a decade ago, and my last solo performance in Vietnam was in 2013 . During the time from 2010-2013, I observed that people in my home country of Vietnam did not engage with contemporary art, especially “happening”-type events. While my artist friends and I had lots conversations about Marina Abramović, especially her piece, “The Artist Is Present” at MoMA – The Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 2010. I was so fascinated by the idea of making a performance piece in that way. However, I guess that was not a good time to make such performances in Vietnam—at least not during that period of time—so I ceased and concentrated on my practice in materials research, because, beside performance, I am also an interdisciplinary artist, working with many media. Of the practices I do in my art, performance is the most intimate; so, I don’t do it unless I have something in my life which is best expressed artistically through performance art.

NC: In this performance you deliberately locked the audience out of the gallery. You allowed them to look through the windows or at the monitor displaying the security-style footage in real time. What for you is the audience’s role in this piece? Is the audience something you consider in most of your art?

QL: Marina Abramović’s works made me think that without the audience a performance wouldn’t exist. So, having the audience unconsciously participate in my performance is a vital part of my concept.

In my opinion, the role of the audience is very important in performance art. This is because of performance art associates with the interpretation in the idea of social engaging. According to Marvin Carlson, “Performance is always performance for someone, some audience that recognizes and validates it as performance even when, as is occasionally the case, that audience is the self”.

If the audiences miss my performance, they never have a chance to attend anymore. That’s why some people came to talk to me they felt regret because they didn’t have enough patience to watch my performance until the end. I understand that my performance sometimes makes the audiences feel uncomfortable because of their own expectations. Thus, this is a kind of evidence, and the audiences are witnesses with all of their emotions and reaction. Even when the audiences stand there and do not do anything, they still play a crucial role in my work.

NC: What did you do to prepare yourself for the original performance of “I Am Not a Spy” in September, 2019?

QL: On the day of the performance, I prepared myself by simulating the conditions of being locked in. I made sure I was very hungry and thirsty, not having eaten or drank anything for a whole day—like the situation when I was locked in the room. And it leads to the same consequence: I was exhausted, felt like I didn’t have any energy to escape—even if I found a way to go on—I almost gave up and thought maybe all the notes I wrote down could speak for me. However, people who didn’t watch my performance from beginning to end probably assumed that because I was so aggressive at first, wildly trying to escape room, wouldn’t have seen my utter weariness and fatigue at the close. I thought that was kind of interesting, too, how surveillance and interrogation completely wear a person out. Perhaps the video this time will suit shorter attention spans.

NC: Your new video work “I Am Not a Spy” currently showing in Singapore is 4:44 of edited footage from your 2019 performance of the same name. How did to decide on the length of the new work? What was your strategy for editing down the CCTV video into the final video? Were you striving to preserve a narrative?

QL: According to my discussion with the curator, we aimed to make a “new piece” based on my original performance for this show. My original show in Knoxville, Tennessee, was around three hours long. However, the new work is a video, not a performance, so I ended up with the idea keeping it short and simple. This is because, after I watched many of my other videos, I strongly believe that I did it the best when I kept them brief. The gallery in Singapore had preferences about the length of the video as well, asking me to extend from two minutes (which was the length I was supposed to shoot for initially) to five minutes. It was a big challenge to shorten my time and still have enough space to show what I wanted to show. Personally, I don’t like to follow anyone’s desire but my own, because it doesn’t feel right to me. As an artist, I make work for myself and so I worked on some draft edits until I was able to edit to 4:44 – the number was significant in that it reminded me of the 44 pages I had written when I was locked in the room. So, I feel very pleased and satisfied with this result. I ended up with an amount of time sufficient to re-tell this story.

Contributor Bios

Quynh Lam is an interdisciplinary artist working in performance, installation, video, and mixed media. In 2017, Quynh was granted by the Fulbright Scholarship to pursue an MFA in Studio Art in the United States. She is a recipient of the 2019 Art Future Prize in Taiwan. She has exhibited work in Vietnam and abroad; some highlights include: The Factory Contemporary Arts Center in Ho Chi Minh City, Art Formosa in Taipei, The Vincom Center for Contemporary in Hanoi, Richard Koh Fine Art Gallery in Singapore, and Mana Contemporary in Chicago, New Jersey and Miami – in partnership with CADAF (Contemporary & Digital Art Fair). Her works have been featured in many publications: Imago Mundi–Vietnam: New Winds Collection (Luciano Benetton Collection, 2015), Saigon Artbook (2016), XEM (2017), Inlen (2017), Frame to Focus: Vietnamese American Women Artists (sponsored by The Catherine G. Murphy Gallery, 2020). Her artbooks–a part of the ‘Vietnam Artist Books Project’ of Indochina Arts Partnership, which was sponsored by the Danish Cultural Development and Exchange Fund–have been accessioned to several libraries, e.g. the MoMA, Yamamoto Gendai, Bay Library, Salon Saigon, Dia Project, UCLA library, UTK John C. Hodges Library (Special Collections), and other art hubs. Recently, Quynh presented at the international conference “ReVIEWING Black Mountain College 11” and she was a fellow of Riedel Fellowship at Ragdale Foundation (Illinois, USA).

Quynh Lam is an interdisciplinary artist working in performance, installation, video, and mixed media. In 2017, Quynh was granted by the Fulbright Scholarship to pursue an MFA in Studio Art in the United States. She is a recipient of the 2019 Art Future Prize in Taiwan. She has exhibited work in Vietnam and abroad; some highlights include: The Factory Contemporary Arts Center in Ho Chi Minh City, Art Formosa in Taipei, The Vincom Center for Contemporary in Hanoi, Richard Koh Fine Art Gallery in Singapore, and Mana Contemporary in Chicago, New Jersey and Miami – in partnership with CADAF (Contemporary & Digital Art Fair). Her works have been featured in many publications: Imago Mundi–Vietnam: New Winds Collection (Luciano Benetton Collection, 2015), Saigon Artbook (2016), XEM (2017), Inlen (2017), Frame to Focus: Vietnamese American Women Artists (sponsored by The Catherine G. Murphy Gallery, 2020). Her artbooks–a part of the ‘Vietnam Artist Books Project’ of Indochina Arts Partnership, which was sponsored by the Danish Cultural Development and Exchange Fund–have been accessioned to several libraries, e.g. the MoMA, Yamamoto Gendai, Bay Library, Salon Saigon, Dia Project, UCLA library, UTK John C. Hodges Library (Special Collections), and other art hubs. Recently, Quynh presented at the international conference “ReVIEWING Black Mountain College 11” and she was a fellow of Riedel Fellowship at Ragdale Foundation (Illinois, USA).

Nathan Robert Cox is a professor of philosophy at Pellissippi State in Knoxville, Tennessee, USA. His specialty is early modern philosophy, especially the work of Descartes, Spinoza, and Hume, and their respective theories of substance. His teaching and research also include meta-ethics, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of language. He is also a poet with several poems pending publication.

Nathan Robert Cox is a professor of philosophy at Pellissippi State in Knoxville, Tennessee, USA. His specialty is early modern philosophy, especially the work of Descartes, Spinoza, and Hume, and their respective theories of substance. His teaching and research also include meta-ethics, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of language. He is also a poet with several poems pending publication.