For a reality series, HBO’s House of Ho is bad at fitting into the confines of its genre. Then again, the Hos are bad at fitting into the confines of stereotypes.

Part of what makes reality television entertaining is the apparent lack of awareness amongst its own stars. It’s never the cautious contestants on The Bachelor who get the most screen time, but more often the unchecked, spontaneous ones instead. Reality television runs on oblivion, or at least the suspension of inhibition at the hands of expert television producers. Yet, despite the amount of drama and humor viewers were primed to see from the trailer, the Hos are strikingly self-aware.

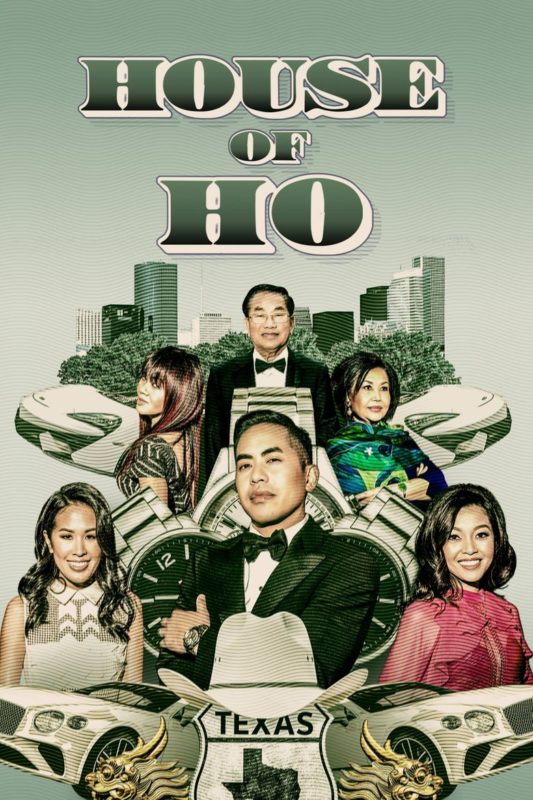

House of Ho follows the affluent Houston family, headed by Bình and Huệ Hồ, but is centered around the lives of their children— namely, Judy, Washington, and Washington’s wife Lesley. As we are given a glimpse into this multigenerational household where lobster is served for lunch and Dom Pérignon is free-flowing, one would expect a kind of floating above reality as wealth tends to afford. However, the Hos demonstrate in large and small ways just how conscious they are of who they are and how they’re positioned in an array of situations. From the eldest child and only daughter, Judy, showing how difficult her life actually is despite how good she makes it look for others, to Aunt Tina’s reveal in Episode 1 of Washington’s nickname as “cái thằng ba xạo” (translation: that boy who’s always lying), the Ho family doesn’t try to convince anyone that they’re something they’re not.

Ironically, then, House of Ho felt almost too real for reality television. In lieu of wildly unfiltered personalities and contrived drama, we are left to reckon with the Hos’ humanity. Without the grandeur of delusions, you can begin to see Washington’s self-doubt, Judy’s exhaustion, Lesley’s loneliness.

What’s most interesting are the contradictions on display. The tensions between simultaneous conflicting truths are central to my experience of being Vietnamese American. Similarly, watching House of Ho makes a lot more sense when you pay close attention to these types of juxtapositions. Bình and Huệ are so Catholic that Huệ brings Virgin Mary figurines for Washington and Lesley’s house whenever she visits. Judy, however, decides to go through with her divorce despite this being frowned upon both from a Catholic and a conservative Vietnamese perspective. The daughter of Bình and Huệ, Judy is persistantly vocal about sex, pleasure, and self-care.

House of Ho is rife with self-contradictions, making it difficult to stereotype the people it depicts. The show is curated in a way that attempts to illustrate just how unreliable and therefore unreducible our narrators are to just one dimension. In the wake of Crazy Rich Asians and Netflix’s Bling Empire, many Asian Americans were reasonably concerned that the family’s wealth would only serve to perpetuate the model minority myth in the eyes of viewers, or that the flaws of the family could be misconstrued as a reflection of all Vietnamese Americans. Yet how can anybody attempt to pinpoint anything the show depicts as representative of Vietnamese or Asian Americans, when there exists so much difference within the same family?

In Episode 4, when Lesley asks the other women in the Ho family to help her keep Washington accountable in his commitment to sobriety, Huệ’s response is to remove the responsibility from her son. Unable to grapple with the severity of the situation, she suggests that Lesley do a better job of keeping Washington happy at home so that he doesn’t feel the need to go out and drink. Despite this, Lesley maintains her assertion: she needs help and can’t support Washington with his sobriety alone. She is then supported by Judy, who reminds everyone that Washington has been drinking for 20 years; this problem existed long before Lesley had entered his life and thus was not Lesley’s burden to bear alone.

Huệ says nothing in response, but has that look in her eyes some might recognize instantly: chin tilted up, eyes averted, but listening. It is the perfect combination of stoicism, deflection, and pride. And yet, we can still sense the truth being heard and turned over in her mind. Lesley and Judy are right and Huệ cannot deny it.

On the surface, House of Ho depicts many cringey aspects of Vietnamese American culture that some of us know all too well: control, manipulation, patriarchal views, the emotional labor of women and related coddling of sons, and more. If we look closer, however, the show also depicts resistance to almost every one of those things. From the third sibling Reagan’s refusal to participate in his family’s politics altogether, to Judy’s quest for independence, and even Washington’s steps towards more responsibility, the series offers up elements that show the characters wrestling with themselves and their familial environment.

Two of my favorite moments from the show are below, exemplifying the Hos as unreliable yet/therefore ever-growing protagonists:

- Throughout the course of the season, Lesley is depicted as more uptight and traditional than Washington and Judy. Washington, in turn, seems to be oblivious to his wife’s struggles and efforts. This was a cause for several points of family tension. In the final episode, however, Washington tells his wife that he appreciates how she is always considerate of their parents’ feelings. Thus, our perpetual jokester is revealing something audiences weren’t sure of for much of the series: Washington does take note of Lesley’s perspective and he admires that it’s different from his.

- While Judy assumed for most of the series and perhaps for most of her life that Washington held a higher position in her father’s heart simply because he was the oldest son, Aunt Tina suggests otherwise: “I’m pretty sure Judy has always been the favorite. [She’s Bình’s] jewel. He always over-protects Judy.”

The Hos may not be very representative of anyone but themselves— which is a good thing because no family should ever have to bear the burden of representing any racial or ethnic group— but they are recognizably Vietnamese in this: so much of the work they do to love each other often lies in the things left unsaid and unseen.

Author Bio

Born in Saigon and raised in Boston and Houston, Thanh Bui is a writer & actor currently based out of Austin, Texas. Her work has appeared in The Offing, Cosmonauts Avenue, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, FIVE:2:ONE, Crab Fat Magazine, FreezeRay Poetry, The Sunlight Press, and other places accessible to her mom. She loves constantly.

Born in Saigon and raised in Boston and Houston, Thanh Bui is a writer & actor currently based out of Austin, Texas. Her work has appeared in The Offing, Cosmonauts Avenue, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, FIVE:2:ONE, Crab Fat Magazine, FreezeRay Poetry, The Sunlight Press, and other places accessible to her mom. She loves constantly.