On February 21, 2021 The Loft hosted More Than A Single Story: Crossing Generations & Racial Lines featuring Douglas Kearney, David Mura, Alexs Pate, and Bao Phi.

This panel presented two generations of collaborations between African American and Asian American male literary artists. The intersections between these four artists explore how poetry and literary culture can form new relationships and understandings and new forms of dialogue between their respective communities. diaCRITICS is proud to publish a transcript of this panel, edited for clarity.

Throughout June, we’ll be publishing this conversation in parts. Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here and Part 3 here. This is the final installment of this conversation.

Alexs Pate: I was just about to say, it’s like you did that because you knew it had admit it would mean something to him. How do you know that? We don’t wake up knowing those kind of things. You have to know somebody. You have to, I mean, all the time that you were talking about, I was thinking about personal pain. It’s sort of like personal journey. I have to know. I have to know and I do know enough about David and about other people who are not me. I have to know enough about them. I have to care. I mean this whole idea of caring. Caring is deeper than knowing. When you care about somebody, you have connected with what I would call, in the work that I’m doing now, their goodness and their goodness is not positive or negative. It has something to do with what generates their existence, and so he knew, I mean you knew, Doug, you might not have known what to say or whether it was the right time to say whatever. It was you. You knew it would resonate with him on some level that manifested back to you as a form of caring. I think, I mean, whether you can extrapolate this community wide.

I live in a world in which I believe that this is possible. I can’t tell you how much I believe that the only answer is this: almost each one feel one or each one care about. It’s like we have to sort of build this again because the power of white supremacy is so deep that it blocks almost every other way in which we can connect on an organic and authentic level. As people who are not the same, we are not the same, and yet we are the same. But the way in which we get the community—how can I communicate with David or with Bao or with anybody who is not, who didn’t grow up exactly the same way I grew up, who didn’t live exactly the same way I lived? How do I do that? We make all kinds of assumptions and most of those assumptions are wrong. By the time we make them, they might have been right yesterday, but they’re not right today. Your relationship and my relationship with David allows us to calibrate and quantify the rate of relationship growth and relationship degradation. There’s a certain way in which I know if I spent not enough, if we’ve gone too long without talking, there’s a degrading element to that relationship, meaning that I can’t really say I know what David is feeling today, but the more our relationship connects…

I don’t know how to extrapolate this out on a community, how to process news that way. So the brother gets the young brother, kills the other brother, and how am I supposed to what, I mean, I don’t even know exactly what my response would be or should be except to denounce the whole thing and the system that created it and the system that gave that kid the belief that he could do this with impunity and that it would cause the death of somebody else that would cause families to mourn. I mean, all of that is individual and yet it is community.

David Mura: We’re taught a certain history. The truth of our histories are left out so we don’t have this background of knowing who each other is. And you know, somebody who we all know has written a thesis, which is being turned into the book, where she talks about how Asian Americans came to America and it’s partly because Texas was a slave state, California was a free state. They didn’t want Mexicans there because Mexicans had to claim to the land. They didn’t want Native Americans there because Native Americans had to claim to the land and they were rapidly destroying them. They needed the source of labor that they could exploit. Asians could not become citizens. They could not repopulate—because the Blacks came to California, they would have children, and then they would populate, and they would become citizens. So that’s why Asian Americans first came here.

When I think about how much of my experience I understand, not just through Asian American writers, but through African American writers, to Latino American writers, through Indigenous and Native writers, and those histories, and that’s all our history. It’s not just one community. You can’t make sense of America unless you know those things. But it’s also bringing that into your life. I mean, I didn’t, I had no almost no contact with Black people until I got to college and there was a certain point in my development where I just felt safer in a crowd of Black people than I did in the crowd of white people. The experience about learning how to navigate through Black space and when to just shut up and be there. The advantage of being a person of color, if you look at it as an advantage, is you can learn so much about America if you’re willing to just go to someplace else, be quiet, and listen. And then there’s a certain point where I realized, I don’t know if I should say it, but I loved Black people like I love Asian people. There are other communities who I have members, who I love, but I don’t necessarily feel like I know enough about the community to feel like I’ve spent time enough with the community that I love. I care about it, but there is love, that is one capacity we can develop. Whiteness cannot keep us from loving and caring about each other.

Pate: We can’t let it.

Mura: The one thing I think is helpful, and I want to bring this around to George Floyd because we all have written essays for the More Than A Single Story anthology and all your essays deal with George Floyd. We all felt that as an incredibly important moment, that we all needed to speak to—

Pate: Can I say something?

Before we go there, I want to say I was hoping that maybe we would all just sort of say this violence that emanates from whatever community, certainly from the Black community, it just needs to stop. We need to do whatever is required, because the conversation can’t progress when that sense of suspicion and lack of faith and possibilities exist. So I just want to: A) condemn, not in some gross big way, but simply the challenges that are before us are too intense to let that go unremarked on. We all have been remarking on it, but I’m just saying, it needs to end. I know there are organizations out there that are working hard to help de-escalate some of this energy, and I just want to support that. I have a biracial child, Asian and Black. I know Bao, you have children, we all have children.

And so our kids have to walk. That to me leads right to George Floyd. It’s like our kids have to walk the freaking streets right now in this world that we live in where all of this is happening right now.

Bao Phi: Thank you, Alexs. I absolutely agree. My child’s daycare, where she spent so much of her life growing up, was three blocks away. So George Floyd was murdered on 38th and Chicago. Pillsbury House is on 35th and Chicago. Literally our children have to walk past that, and I agree with you: the police system on which an Asian American stood by while someone murdered a Black man is unacceptable. It should be unacceptable to any human being with the conscience. I don’t give a shit if you call yourself anti-racist or not, that shit is just not acceptable if you are a human being on this earth. Similarly, the murder of Asian American elders or whoever, for nothing, should be unacceptable to all of us, no matter what mental gymnastics you need to do to get there. It got me that, I’m listening to all of you and I think because of our friendships and our relationships, we feel things both in the broad and in the personal.

Doug, to what you were saying (and thank you for that text by the way), when all this anti-Asian was happening, when George Floyd happened, I remember having the same feelings about you and the Black people in my life and saying like, “OK, this is so massively fucked up across the board. Like what can I possibly do which would be the right thing that would actually help you? Not about my guilt. Not about any feeling of racial responsibility. But what is actually gonna help you as my friend, as a person I care about deeply and my other friends who are Black. How can I actually do something useful in this moment?”

Similarly, I feel like those of us who have these relationships and those of us who are not white, we have to think about this like intellectually and in a broad world sense and also personally. We also have to, so we can think about and break down these different systems that we should. Then there’s the part where we just got to reach out to each other, be like, “Hey, are you okay?” And that’s the labor that we do for one another that we can’t just put out like a theory on the internet or whatever or a thought…We need to do that, but it doesn’t stop there. In our personal lives, we feel it on them in the big picture and on the personal. That is the challenge. That’s the burden that we have. It’s not just an intellectual exercise for us.

Douglas Kearney: Exactly. There was the piece that’s being anthologized, a letter to the editor that I wrote. There are a few people who I showed it to before I distributed [it] and Bao was one of them. I just remembered thinking, as he read drafts of it, I just remember thinking to myself that this could do, this could be it, [this] could be a cathartic letter. I don’t tend to believe in catharsis like that. So it could just be a thing that I send out to the world or it could do multiple kinds of work that I believe is good work. Sending that to Bao was a way of trying to make sure it would do as much good work as it could. It’s funny because like you don’t know what’s going to happen with it, you don’t know how people are going to take anything that you do. I didn’t want to tell, I didn’t want to put it as a part of my life, like you know, don’t worry these different people looked at it. It’s not about them endorsing. It’s not about them saying “I gave this a pass,” and that’s that place that you’re talking about, Alexs. There’s this personal space and then there’s this communal space and some of those activities are not scalable. Like the fact of the matter is we’re sitting here right now and all I can see are the three of you and myself. If I could see everybody here that’s listening right now or that could listen to the recording of the video in the future, so even this mode, which feels intimate, I just want to keep returning to the idea of this is living, this is not a finished project. This is not a presentation. This is not a presentation and so just trying to learn from each other to get moments of correction that are given in good faith to push towards an understanding that somebody else might not have. That’s the great gift of this friendship for me.

Contributors’ Bios

Douglas Kearney’s work as a poet, performer and librettist has been featured in many fine publications and venues in print, in-the-flesh and in digital code. His first full-length collection of poems, Fear, Some, was published in 2006 (Red Hen Press). His second manuscript, The Black Automaton, was chosen by Catherine Wagner for the National Poetry Series and was published by Fence Books in December 2009. In 2010, it was named a finalist for the Pen Center USA Literary Award in poetry. In 2008, he was honored with a Whiting Writers’ Award. He lives in the Valley with his family and teaches courses in African American poetry, opera and myth at California Institute of the Arts.

David Mura is a memoirist, novelist, poet, and literary critic. He has written the novel Famous Suicides of the Japanese Empire and two memoirs: Turning Japanese: Memoirs of a Sansei, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and Where the Body Meets Memory: An Odyssey of Race, Sexuality, and Identity.

Alexs Pate is the President and CEO of Innocent Technologies and the creator of the Innocent Classroom, a program for K–12 educators that aims to transform U.S. public education and end disparities by closing the relationship gap between educators and students of color. The Innocent Classroom has partnered with districts and schools throughout the United States, training more than 7,000 educators. The success of the Innocent Classroom has led to the development of Innocent Classroom for Early Childhood Educators and Innocent Care training for healthcare professionals to build connections with their patients. Alexs is the author of five novels, including the New York Times best-seller Amistad. Prior to these pursuits, Alexs was a professor and teacher at Macalester College, the University of Minnesota, Naropa University, and the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Creative Writing Program, where he also earned an MFA.

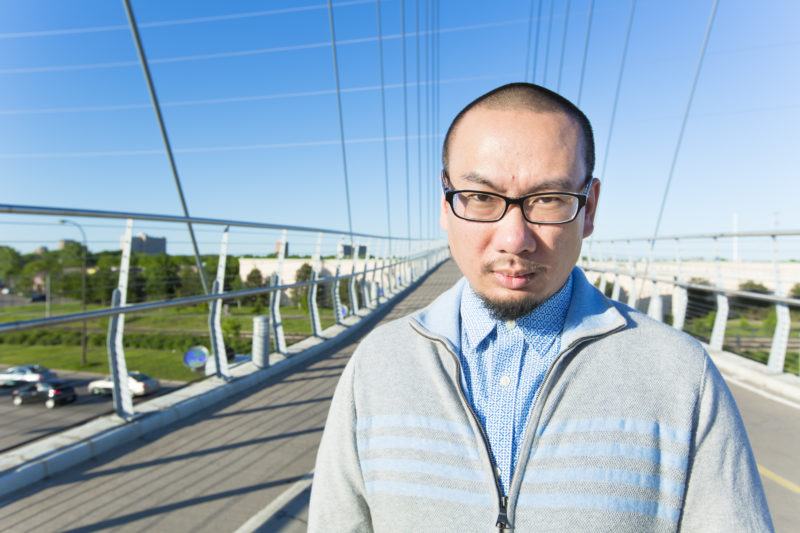

Bao Phi is a spoken word artist, poet, children’s book author, arts administrator, and father.