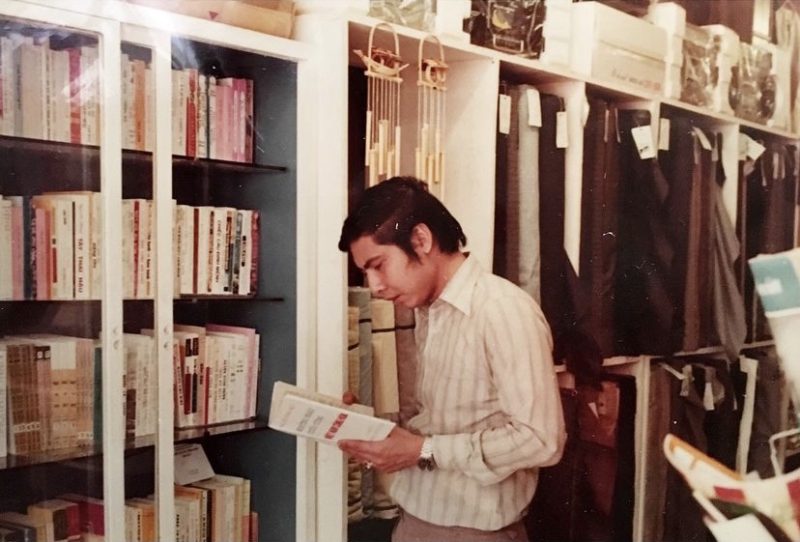

My father wrote a book, which he spent much of the last decade researching and writing without cease. It is over 2,000 pages. I am unable to read it because it is in Vietnamese. “What’s it about?” I asked him at dinner one night. “Vietnamese literature and language,” he said, “from the very beginning.” While the project is sprawling, he attempted, in part, to make visible Vietnamese texts destroyed and erased, literally burned in fires, after the takeover of Communist North Vietnam in its mission to assert its will during the country’s forced reunification. He tracked down hidden books that escaped these mass burnings, and he paid an absurd amount of money for their safe travels. He wanted to offer a history of his country that exists in darkness, obscured by the victors and by the fragile ego of Western memory.

He said he knew no one would publish it, but he had to write it anyway, and so, he spent his own money to publish it himself, money set aside in a savings account over the course of years for this very purpose.

He was an important member of the South Vietnamese Army, responsible for the security of borders and prominent government officials. As a member of the losing side, he came to America and worked, at first, as a dishwasher. There are so many others like him. Erased by the winners of war, invisible in a place that didn’t—perhaps still doesn’t—want them. He was obsessed with writing this book, which he viewed as a record of events, an assertion that he had, in fact, existed, that the Vietnam he remembers existed. He sold the books primarily to other literary Vietnamese of his generation who are now scattered across the globe in the United States, Canada, Australia, France. “No one cares about us,” he said of himself and his fellow diasporic generation. “I am not American like my daughters, and I am not Vietnamese,” he said—not anymore, not in its modern-day iteration. The Vietnam he knew is a ghost, his identity formed around a corpse. He is an outsider wherever he is, unknown to both the country he inhabits and the country he inhabited.

*

He passed away in mid-January. In the months after his death, I scrambled desperately to document details of this last year of his life, which was marked by chronic illness and which now blurs and blends into one large puddle, essentially disappearing into the mass of grief that overtakes us when a loved one leaves. I collected parking garage tickets to help remember when I’d gone to visit him in the hospital. I wrote down in a single document all the dates of his doctor’s visits, his surgeries, his home health appointments, collaged together from calendars and scribbled post-its. I’d spent an extraordinary amount of time with him in bland hospital rooms, a witness to the withering of his body, and yet, I could not account for any of my time. The only way for me to distinguish these stretches was by recalling the notable moments of medical dysfunction built into our for-profit American healthcare system. As someone on a privatized form of Medicare (What?), my father’s treatment and its costs were haggled over inefficiently by the insurance company and his doctors. There is no way for me to disentangle his death from this fact.

Now he is an absence around which I try to patch together a memory. With his departure, an entire history, yet another gone from a generation that exists in-between, now a pile of dust. This disappearance panics me—who will remember him when the people who remember him are gone? This is how erasure happens: pushed to the margins; a history overwritten by a different, dominant one; disappearance, death in different manners—through violence, institutionally mandated neglect, or both.

*

When my dad acknowledged me as a writer, he began telling me about his life and the details of his book. I decided to do my own research on the subject matter he was writing about, the roots of Vietnamese language.

In 111 B.C. the Han in China conquered Nam Việt, what is today known as the northern part of Vietnam. The Chinese brought with their conquest chữ nôm, a modified system of Vietnamese writing stemming from Chinese characters, and a complicated love-hate relationship toward the Chinese that persists into the present day. Chữ nôm literally means “southern characters,” indicating, from the Chinese’s perspective, that the conquered Nam Việt were simply the southern part of the Han territory, an extension of China. (Incidentally, my father argued fervently for the opposite—that actually the Chinese took and based their own language on early Vietnamese.) It wasn’t until as late as the 19th Century that Vietnam adopted Latin characters for writing, delegating chữ nôm to a place of ceremonial value and academic elitism. However, chữ nôm had come to represent not Vietnam’s Chinese conquerors, but the language of national identity, of Vietnam’s ability to take outside influence and make it our own.

When the French colonized Vietnam, they institutionalized the use of quốc ngữ, the Romanized character-based Vietnamese brought to the country many years earlier by Catholics. Part of the colonist’s first assertion of power over the colonized is to erase the colonized’s language. Any transgression against this mandated language was, of course, violence. If you resisted enough, it was cause for death. It makes sense, doesn’t it? If you are not permitted to speak in your chosen tongue, you are stripped of agency at its most basic level. The way we speak is tied in all kinds of ways to how we form our identities, both individual and national. We hear it all the time in America, despite there being no official national language—“Learn English or get out,” you might hear someone say about Mexican immigrants, as if a group of people speaking Spanish in Los Angeles somehow taints or corrupts a particular vision of American identity. This, of course, in no way addresses how Mexicans came to speak Spanish in the first place. In any study of any country that has been colonized, a systemic erasure of native tongue replaced with the colonist’s language can be found. Why do Filipinos have last names like Bautista, Cruz, García, and Torres? Why do Madagascar, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Niger, Senegal, Benin, Togo, and many other African countries speak French as an official language? Our tongues are the first place on our bodies where power must be forcibly seized.

What’s funny about the French colonial language policy is that it backfired. The forced implementation of Romanized characters, quốc ngữ, as the country’s official means of communication, was at first deemed by the Vietnamese as the oppressor’s tongue. It represented the outsider who wanted Vietnam to change, to submit to Western rule. And, let’s be frank: that was what it was—France hoped to isolate the Vietnamese from their cultural roots and create a new kind of culture, one that France dictated and controlled and to which the Vietnamese submitted.

But then, the Vietnamese realized that quốc ngữ was easier to learn, unlike the complicated, cumbersome characters of chữ nôm, which had only been learned by the elite. Literacy began to spread to merchants and farmers, to the people. Quốc ngữ was used to translate works of literature, and then, to write Vietnam’s own modern, newer national literatures. It proved itself worthy of the Vietnamese people, complex enough to convey the minds of its complex citizens. And finally, one of my favorite ironies, it became the language of Vietnamese nationalists, as they began their campaigns for independence. Quốc ngữ, the intended language of collaboration and colony, of Catholicism, became the foundation for violent resistance, insistent independence. I suppose, in a way, this was also the foundation for my own family’s eventual expulsion from their homeland. Language, both a source of freedom and a means of oppression.

*

I haven’t had the courage to talk to my mother about violence. More than 6,600 Anti-Asian hate crimes have been reported in the US since the start of the pandemic, and more than a third of those crimes were reported in March. An Asian woman who had her head smashed in with a hammer. An elderly Asian man pushed into the street and kicked, another stabbed. If my dad were alive and we had this conversation, he would probably laugh. He would tell me not to worry. Part of me feels it is absurd, too. You just don’t like Asian people, the way they smell, the things they eat, the language they have the audacity to speak within your earshot? You don’t like to see an Asian person wearing a mask? And so, your reaction is to throw a violent temper tantrum?

Except I know it is more insidious than that. Embedded in this violence is a belief that we don’t belong. I am foreign no matter how many degrees in English I might gather, like plastic talismans against a monster trying to kill me. I walked home from my job on Thursday and for a full block imagined a passerby driving a knife into my abdomen simply because I existed in a space in which they might not want me to exist. The attacker wants me to stop talking, be silent, disappear. What is the objective of violence? It is erasure. Erase this body, all of its history, so that its absence, its silence, can be filled with another narrative.

Maybe I write because if someone, a person, a system, tries to erase me, someone will be able to read this and remember that I existed. I understand my father a little bit better in the midst of this moment. Someone—a person, a system—has tried to erase him. In fact, they have been successful in erasing the literal space of his home, the bodies of his friends, his family, the physical and material manifestations of culture, identity, nation. A lifetime of this, I am sure, is why he was so adamant about leaving a record. Because the record of language, of his voice, is proof of life.

Contributor’s Bio

E.M. Tran is a Vietnamese American writer who was born, raised, and currently lives in New Orleans, LA. Her debut novel, Dragon Tiger Goat, is forthcoming from Hanover Square Press/HarperCollins. Her short stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in such places as Joyland Magazine, Prairie Schooner, Harvard Review Online, and more.

E.M. Tran is a Vietnamese American writer who was born, raised, and currently lives in New Orleans, LA. Her debut novel, Dragon Tiger Goat, is forthcoming from Hanover Square Press/HarperCollins. Her short stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in such places as Joyland Magazine, Prairie Schooner, Harvard Review Online, and more.

Fascinating on many levels, and a lovely tribute to you father.