Over a year ago at the start of the pandemic, my children stayed home from school and our family weathered the first of many weeks at home. The days were indescribably busy, full of joy even, but they brought with them a particular loneliness. It was an extension of the loneliness I had felt for the past several years since the birth of my daughter and then my son and then, eventually, the birth of my academic book, which was nearly in the world. I had pushed away everything that wasn’t diapering, breastfeeding, and moving the book forward—what I thought essential to the survival of my children and my ability to provide for them. I was eager to write creatively, to connect with other artists in the diaspora, and to find out how mothers make art.

I’ve learned to hide that I’m a writer who mothers and a mother who writes. Mary Antin’s example haunts me. Her daughter spent more time in boarding school than in her mother’s autobiography. A mere note in the acknowledgments, she doesn’t even come into the three hundred plus pages of The Promised Land. Rebirth is more commonplace in this genre. When Antin writes, “I am just as much out of the way as if I were dead,” she is writing about coming to the United States. But these lines are also an indictment of motherhood, of the utter displacement of mother by child and its grim reversal by the writer who displaces her child outside the bounds of her autobiography.

In the first few months of the pandemic, I often stood with my children at the kitchen window thinking about my unwritten projects: a book of poems, a family history, several short stories in need of revision. Seismologists said that the earth had quietened during quarantine, and it seemed our capacity to listen had also grown, as we learned to communicate across doors and windows and the prescribed feet of distance. An egret crossed the driveway looked for lizards in the verge. From outside the shut glass, we were inaudible. The bird became a regular visitor during lockdown.

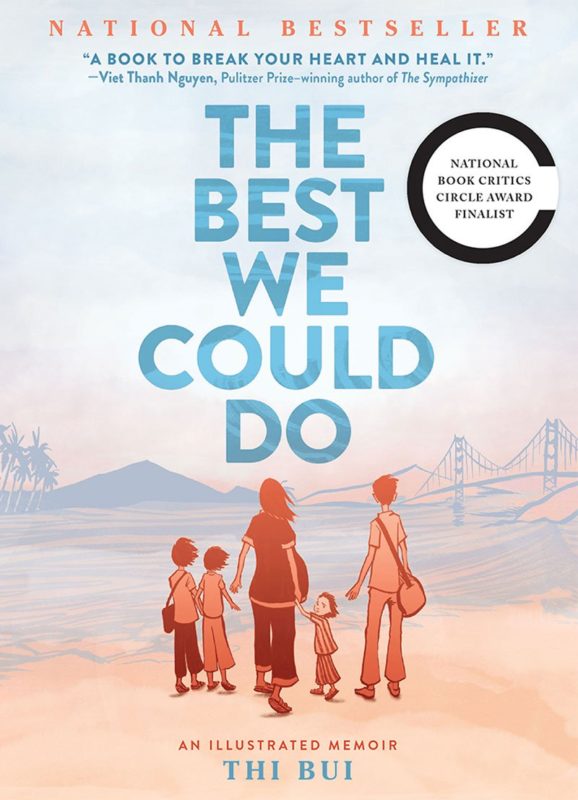

One night I picked up Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do and noticed that Bui begins her illustrated memoir of refugee migration with the birth of her child. Is this allowed? My first thought was a child’s question. It hadn’t occurred to me to involve my children in my story. I had an idea of creativity that pushes children aside, that waits until I deliver them to other caretakers and shut the door, clearing a path through socks and toys to the first quiet breath at the computer and the luxury of missing them while I write. Bui’s book came when I needed it and kept me company, showing how children impel art making out of displacement that clears the path to our shared lives.

At first, I read as I usually do, with an observed distance. Bui’s story is not my story. There are no suitcases, no illusions of choice. The ruin of colonialism and war is written into these pages. Taut mothers, strained by the need to nourish and survive. Fathers who seethe with pain and flare into madness. Children whose view of stars is framed by a boat hatch. All forced by imperialism to flee into the bind of American life that sets North against South, Vietnamese against American. A little thing brings me closer: the motif of sun and stars on a breastfeeding pillow repeated across several frames. Here is the mother. She is not me. Here is the baby. Is he mine? Here is the mother and the baby. As Thi figures out how to nurse, I cry, embarrassed that of all the moments in the book this is the one that has moved me.

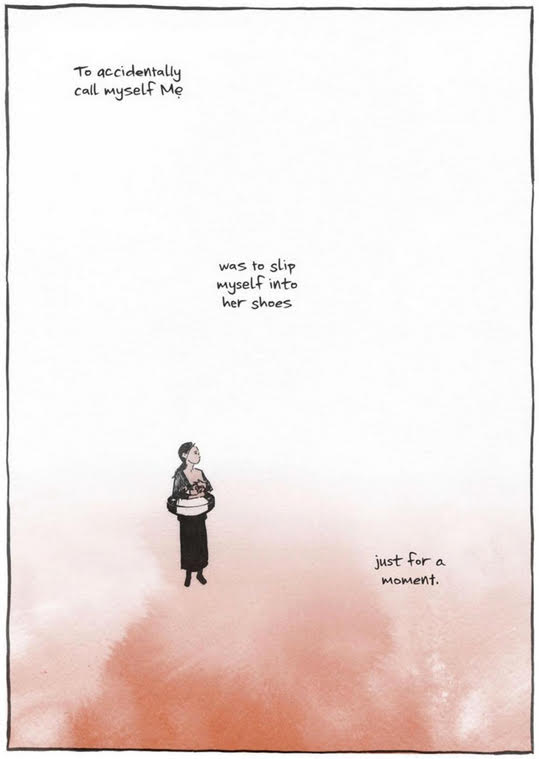

When I sought a reason to have children, my father asked, don’t you want to experience all of life? Reading had been the access to that breadth. Now, hard as it was for me to accept, the experience of motherhood had changed even how I read. Skeptical as I am of the closeness to other mothers that is said to come of motherhood, I couldn’t help but take a different path through the book. Thi brought her bassinet to the mirror and we walked the antiseptic halls, finding our sea legs. The stakes were higher. What we shared as mothers deepened the violence of incomprehension.

When Thi’s son arrives, he is singular yet representative, utterly himself but also like every other newborn. The splash page pulled me in. In a dream, my daughter too came to me with old eyes, grey from a view on another world. During my pregnancy, I imagined her swimming alongside migrating whales, barnacled platforms, oil seeps, dolphins, sea dogs, and long-billed birds on the wrack line. She arrived just as I caught her, Lakshmi’s namesake, churned from the primordial sea.

A child prompts inventory. Before my daughter was born, I sorted. Her room was piled with old boxes filled with yearbooks, school certificates, hard-won swim badges, class notes in the event I had to relearn algebra. Continuity was the problem. How to draw the line?

When Thi is in labor, her mother disappears. There are no grandmothers, rustling ancient underwear. How lonely the pain of birth and afterbirth when our bearings are gone. Over months, I opened the freezer, unscrewed a blue bottle, and took a small brown pill, building my body into a ground. “Hrmph!” Thi gags at the sight of her placenta. The symbolism is too strong. Where the baby’s life meets our body, anything might be passed on. This is Thi’s fear as well, that heartbreak might be inheritable.

So freedom has the last word, as Bui ends with the image of her son swimming out to open water. Hope. Benediction. The image conjures others like it in which Thi’s mother, father, and Thi herself set out in search of freedom. My daughter, too, is named for freedom. What it means is as different as our experiences of migration. Financial security, clothes that fit, immigration papers, a healthy feeling for difference, staying somewhere long enough to plant a garden.

Lately, everything I write as a mother feels like a prayer. Or I’m taking stock, drawing a map of my immigration story so my children can make their way through without getting lost. In one future I like to imagine, the pandemic recedes and our window opens. Unfazed, the egret stalks into California brush. Through our door and through many others, my children retrace my steps to India and the village that joins them to this world. The old version had me at my desk writing, but I’m right there now. Where two plots meet is the mulberry tree my father planted, where I would have buried the afterbirth. The hard-packed dirt has softened. We sit awhile, shaded from the hottest sun.

Contributor’s Bio

Swati Rana is Associate Professor of English at University of California, Santa Barbara. She is the author of Race Characters: Ethnic Literature and the Figure of the American Dream, recently published by University of North Carolina Press. Her nonfiction, poetry, and fiction have appeared in The Paris Review, Granta, Crazyhorse, The Asian American Literary Review, Wasafiri, and elsewhere. Visit her website: www.swatirana.com.

Swati Rana is Associate Professor of English at University of California, Santa Barbara. She is the author of Race Characters: Ethnic Literature and the Figure of the American Dream, recently published by University of North Carolina Press. Her nonfiction, poetry, and fiction have appeared in The Paris Review, Granta, Crazyhorse, The Asian American Literary Review, Wasafiri, and elsewhere. Visit her website: www.swatirana.com.