Working From Home / may ở nhà is a book that weaves together journalism, illustration, and oral history to tell the stories of Vietnamese outworkers in Australia. In this conversation, James W. Goh talks with fashion writer Emma Do and illustrator Kim Lam about how they came to publish a book about those sewing from home, the process of recuperating neglected history, and the precarity of migrant labour.

James W. Goh: I’d like to begin by situating you both in the project. At the beginning of Working from Home / may ở nhà, Emma, you write, “Sewing cropped up in oral histories and memories from the Vietnamese diaspora as a passing mention, yet never emerged as a story of its own.” How did you come to learn about these overlooked stories and what interested you about the lives of Vietnamese outworkers?

Emma Do: I became interested in the stories of Vietnamese outworkers because there was a bigger movement in fashion for transparency and finding out who made your clothes, which was brought on by what happened at Rana Plaza—the 2013 Dhaka garment factory collapse. When I was writing about fashion in Melbourne in 2015-2016, I was always keeping abreast of the marketing that brands were doing around who made their clothes. I noticed that they would show their makers and list their names on Instagram and other media. I realised many of these names were Vietnamese. As a Vietnamese person from Melbourne, I didn’t know that there were so many Vietnamese people working in local fashion production so that was the first thing that stuck out to me.

I didn’t really think about making it a real project until a good friend of mine told me that her mum had gotten a new job, making samples in a factory. Although I had known this friend since high school, I had never known what her mum did because we never talked about it. She mentioned this off the cuff, and because I was interested in fashion, I asked her more about where her mother worked, what she did, and it came out that her mother had been an outworker ever since my friend was born.

My friend mentioned that she didn’t really want to talk about it back when we were in high school together because it’s not a job that’s considered normal. It’s not like “my mum worked at the bank” or “my mum worked at the factory.” It’s such an informal job which happens at home that I think she didn’t know how to talk about it when she was younger. That made me more interested to learn about this whole world. Eventually I found myself asking every single Vietnamese person I knew: family, friends, and all. Basically everyone said they knew someone who was an outworker; it was either their parents, their family friends, or someone in their orbit. I thought if everyone has a connection to outwork, why don’t we have a dedicated story to it so we can learn more about our Vietnamese Australian history?

James W. Goh: And Kim, how did you become involved in the project?

Kim Lam: Emma and I had been intermittently bumping into one another in our overlapping community circles both on- and offline. I was also an admirer of Emma’s various fashion-related projects. So when she reached out for a coffee catch-up to explore a potential collaboration on Vietnamese outworkers, I was already warm to the idea!

Moreover, I grew up amidst outwork—babysat by aunties, uncles, family friends, and even borderline-strangers in the after-hours when my parents couldn’t look after my sister and I. Being among the outwork environment was very normal, something I didn’t ‘see’ back then. My parents weren’t outworkers themselves, but they worked in garment factories before eventually transitioning to other professions.

James W. Goh: Both of your points about the omnipresence of Vietnamese outworkers are so true. Flicking through Working from Home / may ở nhà made me realise how they’ve always been in my orbit too. I remember when I was in high school, I had to have my Year 10 formal pants shortened. Late at night, my mum took me to see a Vietnamese seamstress in this unmarked house in Cabramatta. It was my first time wearing any kind of formal attire, and I didn’t want to embarrass myself with shoddy alterations. I remember asking mum, “Are you sure she knows what she’s doing?” In hindsight, that was incredibly naive and short-sighted of me. We picked up the pants on the next day, and the alterations were perfect.

Kim Lam: Yes! I have my own current-day, Vietnamese suburban version of that seamstress, so I think this is still something that is very much alive.

James W. Goh: Definitely. I think that that shows in the book. Throughout the book, you’ve incorporated oral history testimonies from so many different sources: the makers, their families, and the Textile, Clothing & Footwear Union of Australia. As you’ve already mentioned, Emma, talking about outwork must not always be easy for the makers or their families. What was it like to get all these different people involved?

Emma Do: The starting point was finding outworkers themselves or people who had been outworkers. We put the call-out to friends and family. Kim obviously had some contacts. If people said no, they might know someone else. We just kind of chased people like that, which is really hard because you’re cold calling people a lot of the time or you’re relying on this mutual person that that other person knows. We had to rely on others vouching for us. For example, in many cases, we asked friends or friends of friends to ask their parents. The fact that we could speak Vietnamese, I think, did help. We could say, “We can speak to you and document your stories in Vietnamese so that it’s easier for you.”

We mostly found the outworkers themselves through friends, family, social media call-outs, and some factories which we contacted. For example, there’s Vinh, who is featured in the book and has a factory in Melbourne called Denimsmith; he was really happy to talk. We also had other factory owners, but they needed a fair bit of convincing and they asked to go anonymous.

Kim Lam: We also relied on scanning our Vietnamese memory log of where we recall having seen Vietnamese names. Or sometimes it was just remembering seeing a Vietnamese face among the portraits posted as part of our local “Who Made My Clothes” movement. Emma and I went through all the labels we could think of and wherever we might have seen Vietnamese workers.

Emma Do: I think it helped also that we’re second generation. We’re the children of refugees and migrants so we could reach out to other people in our generation who understood the project and where we were coming from a little more. They could put in a good word with their parents who might have been in the industry. It took more convincing and explaining when approaching outworkers directly—I imagine it’s strange to have these two young people asking you about your working life for some intangible book project. They were naturally wary at first.

As for the Textile, Clothing & Footwear Union, I approached them because I wanted to understand their perspective, as outwork was a really big issue for them. They campaigned to change laws, especially in the 80s and 90s, so I thought it was really important to understand that historical context and where that issue sits with them today. For the record, outwork was and is legal, provided that outworkers are paid minimum wages and super. The union wasn’t necessarily trying to stamp out outwork, but were trying to regulate it, because most of it was flying under the radar.

James W. Goh: Before we dive into the stories in the book, I wanted to ask about the form of the book itself. Thematically Working from Home / may ở nhà resembles Vietnamese diasporic texts, which delve into experiences of resettlement. I think of Carina Hoang’s oral history Boat People: Personal Stories from the Vietnamese Exodus 1975-1996 and Nathalie Nguyen’s Memory Is Another Country: Women of the Vietnamese Diaspora, Nam Le’s memoir The Boat, Matt Huynh’s comic Cabramatta and Thi Bui’s graphic novel The Best We Could Do as well as Ocean Vuong’s novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. Your book melds together journalism, oral history, and illustration—how did the book come to take this specific form?

Emma Do: When I was doing research on outwork, I mostly came across academic studies so I was really hungry to see this subject talked about in a much more accessible way because I don’t come from an academic background. I come from a more journalistic background so that’s how it started for me. I wanted to interview people and let the story speak for itself. One of the issues I came across was that I was interviewing people who did not want to be photographed. I thought the story would be less engaging without visuals and that’s when I thought about asking Kim to illustrate. It was a very practical arrangement for us to choose this format actually. When working with Kim, it was this completely new process for me, melding the journalism, oral history, and illustrations so they all talked together to create this new work. It’s something I had never done before.

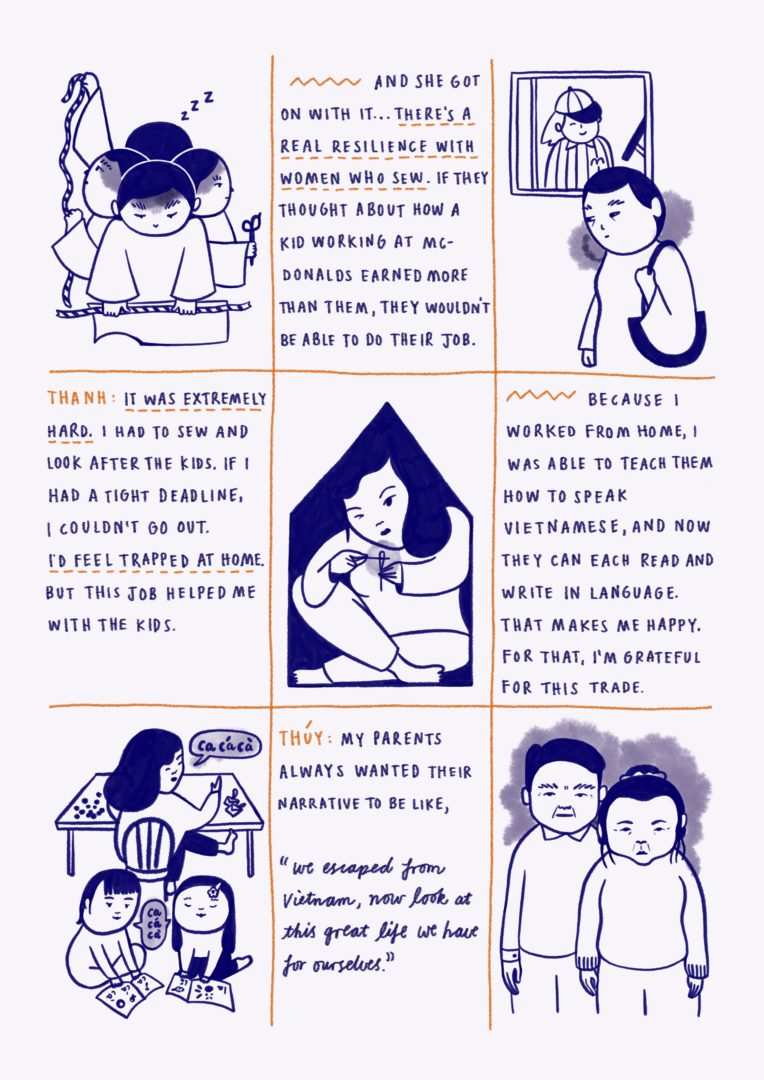

Kim Lam: Illustrations do add a whole other layer of emotional expression and storytelling, as well as being able to communicate without the need for traditional ‘written’ language. Other than providing visual engagement, illustrations and comics also render the book more accessible and friendly feeling! The topics traversed are heavy at times. And as Emma mentioned, we literally wanted the people we interviewed to speak for themselves, and depicting this in comic form made sense. As for being a book, I guess it had always seemed like second nature that it was going to be a printed thing. In honouring the labour of outwork, I personally really wanted an element of the hand in the project’s direction: hand-made, hand-writing, something you can physically hand to others.

Emma Do: Yeah. It was also about keeping the intimacy of the interviews. People invited us into their homes, their lounge rooms, or their workplaces and sat with us for a few hours and told us their life stories. Kim and I did the interviews together, and we wanted to keep the spirit of the intimacy of those interviews in the book. We wanted to translate it across the printed form, which is harder than if you’re recording audio or video. I think Kim did such an amazing job of conveying that intimacy through her lettering, which is based on her mum’s handwriting, and obviously through the illustrations which are super emotive and just beautifully paced across a lot of sections.

James W. Goh: Agreed. As I read the book, I grew fascinated with the form because the various elements worked so well together: firstly, the journalistic research provides key Vietnamese and Australian historical context about the U.S. war in Vietnam, Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser’s refugee program, the end of the White Australia Policy, and the xenophobia which lingered despite the rhetoric of multiculturalism that inaugurated the 1970s and 80s when Vietnamese resettlement largely took place; secondly, the oral histories cast light upon family life, the conditions of labour at home, and moments of joy; and thirdly, the illustrations humanise the outworkers who are largely sharing stories about sacrifice and hardship. Together, I felt like the prose and illustrations sensitively explored how the families persevered and how there is hope at the end of it all.

Emma Do: I’m so glad that you felt that there was joy coming out of the images because that was definitely our intention. When you read a lot of outworker stories, you only get a certain angle because many of the stories were documented to push for better conditions and laws. The union, who gathered these stories most of the time, wanted to highlight the plight of outworkers to garner public support for their campaign, but in doing so, it also became “look at these poor people.” That really does reduce people’s humanity. We wanted to be able to take that back a little and show that outworkers were people with families and that they were doing their best and that there was joy to be found as well.

James W. Goh: I think the book definitely nods to those personal and political dimensions of outwork. I really appreciate how it places Vietnamese outworkers in the midst of multiple interlinked narratives of nation, diaspora, labour, and family. Early on in the book, you ask, “How free are you if your family is suffering?” I kept returning to this question as I read the book because it so deeply strikes at core elements of diasporic Vietnamese experiences. For many people, the story of ‘Vietnam’ has a teleological structure from unfreedom to freedom, from the illiberal so-called “Third World” to liberal capitalist democracy. At the same time, “The Bottom Line,” one of the excerpts from your book, emphasises how the reality of life in diaspora is far more precarious as the makers felt pressured to work in every spare moment.

Emma Do: Yeah. I actually didn’t think about that quote having that double meaning until you said it, but it makes perfect sense. When I was writing it, I was thinking about the fact that these outworkers had been refugees, they’d come over here, and they were enjoying parts of their freedom, but it was still such a tough life. It was tough because they had all their family back in Vietnam so they needed to work and save money to sponsor them and that kind of thing. At the same time, finding your feet as a refugee in any country is so goddamn difficult. Your family will suffer through those early years as well. People expressed that it was difficult to find jobs which they had been trained for in Vietnam because none of their qualifications were recognised.

Outwork became popular in the Vietnamese community because it was something you learned about from your friends. You could get work from your friends without having to do an interview, speak English, or go into this factory or unfamiliar environment. You could save up for a sewing machine. In that sense you had a certain amount of control over your work life, which might not have been available to you when you were looking for jobs outside. So, you were in charge of your hours to a degree. You were in charge of where you worked. You were able to make the choice to look after your kids at the same time. That was why people were attracted to outwork. It gave them a certain amount of autonomy when they were faced with few options in what they could do for a living. And you know, some people saw outwork as their little business and were proud of that. It’s not like they were out there working for the man and being exploited by some crap boss, even though these were still arguably exploitative conditions. They felt like they could have a certain amount of control over their income and their business.

Kim Lam: I agree with Emma. And I think they just felt like they had to find work wherever it had been available. I also think that the spirit of Vietnamese people is often marked by a strong streak of doggedness, single-mindedness, and persistence. Piece-by-piece outwork offers a visible sense of progress. As manually exhausting as it may be, there is motivation in sewing “just one more garment” until you’ve made hundreds and you’re tallying your income in real-time. I think that that sense of control, a so-called freedom does emanate from that structure of work. There is lucrative potential in that, but only when you don’t compare it alongside the huge hours put in and the physical repercussions.

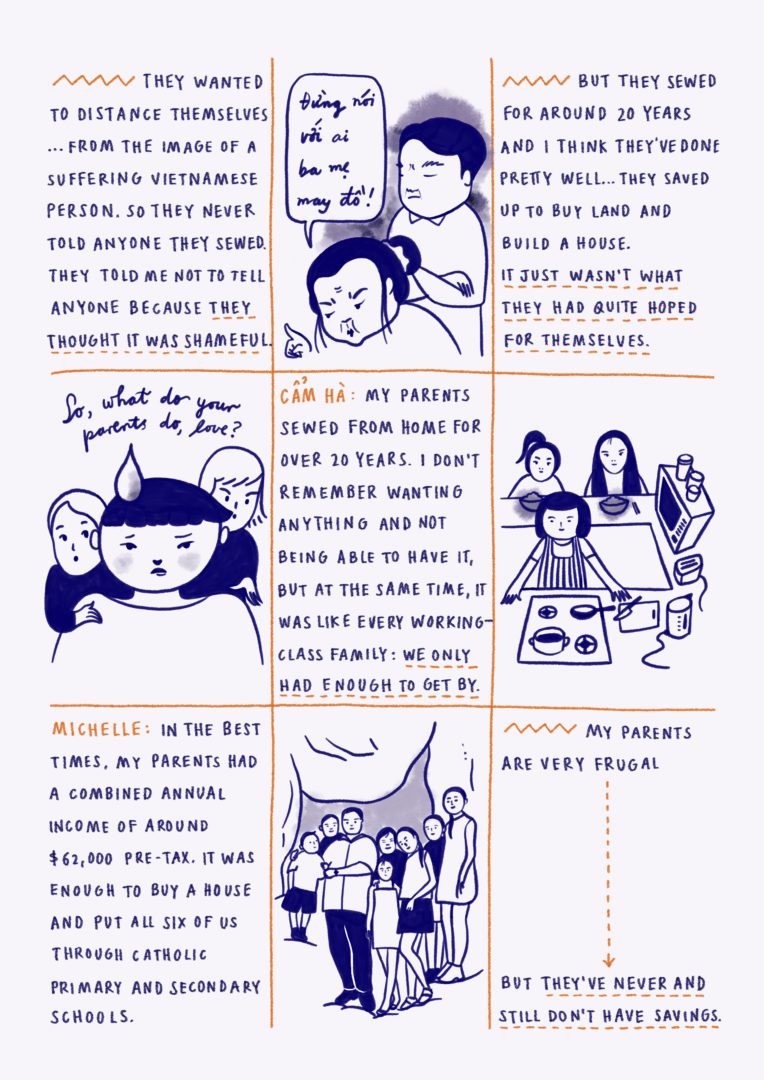

James W. Goh: Let’s talk about family because I think that one of the key achievements of the book is the way in which you humanise the makers such that they aren’t simply reduced to their labour. They’re people who have their own agency, aspirations, obligations, and relationships with others. While the parents treated the difficulties of outwork as a fact of life, their testimonies seemed to gesture to an underlying familial or filial economy of debt and care. I’m wondering if you could speak a little bit to the way in which the parents and children’s relationships were triangulated by outwork.

Emma Do: Yeah, it’s complex. All the children we spoke to were like, “Oh, my relationship with my parents is so complicated, not just because of sewing of course.” I think it’s so different for all the families. But when we spoke to the children, there was the sense, maybe not of outrage, but of seeing that what their parents went through was not right, and they shouldn’t have gone through those hardships for such little pay. Maybe, at the time, they were too young to do anything about it. They didn’t really know about minimum wage, but they could see their parents working all night and being sore. They knew that’s not the way it should be in Australia. One of the children we interviewed (who is an adult now) told us that her parents used their work as a way to guilt-trip her into working and studying harder: “look at us. We’re self-sacrificing, and it’s all for you. We wouldn’t be sewing 12 hours a day if we didn’t want the best for you, so the least you could do is get good grades and get into this uni.” Or that kind of thing, which is very classic Asian parent self-sacrificing talk. I don’t know if that’s specific to outworkers though.

Kim Lam: A lot of the time it seemed like the children didn’t have a feeling of agency during their childhood—I guess this is a common trait amongst children in general! They were witnesses, and often didn’t feel like they could exert influence on their parents’ life choices. That’s why Vo’s story really stood out—they described themselves as having to perform a caretaker role for their parents. Overall, we didn’t direct our interview questions towards the topic of care—it just feels too intimate in the Vietnamese culture to bring that up, don’t you think? We don’t talk about care as a topic. It’s not literal. It’s just expressed, just is.

Emma Do: I think everyone, including all the kids, knew their role in the family though, especially the big families where everyone would pitch in and sew in the afternoon after school and on weekends. They knew that as children they were expected to do certain things for their parents. And maybe that’s a form of caring. This is what you have to do for your family. You have to help the family make money by working after school.

Kim Lam: And some of them got pocket money for it!

James W. Goh: Yeah, I see. Throughout the various accounts, there seems to be not only a sense of pride in persistence but also shame. In the grid comics accompanying “The Bottom Line,” one of the children talks about their parents saying, “They wanted to distance themselves from an image of a suffering Vietnamese person. They never told anyone they sewed. They told me not to tell anyone because they thought it was shameful.” How exactly did this family imagine their ideal narrative as a Vietnamese person?

Emma Do: This is very much a class question because outwork was seen as lowly. It was not a particularly glamorous job, and you wouldn’t be doing it if you had a higher status. These parents in particular were very class-conscious about the perception of their family. They were friends with a lot of people who were like “bigger deals” in the community.

Kim Lam: I feel like it depends on which interviewees we’re talking about too, which is why we profiled lots of different voices in that grid. These particular parents really wanted to build a completely new narrative for themselves after migrating to Australia—it was their Australian Dream, and so much of it was informed by how successful they thought they could appear in the eyes of others, and outwork just wasn’t a part of that picture for them. And so they actively distanced themselves from a lot of the Vietnamese community, whom they hid his occupation from.

Emma Do: They kept on sewing for all of those years. They just hid it from all their Vietnamese friends and pretended that they did something else.

James W. Goh: I have a final question about the attention to labour and migrant workers that is threaded throughout the entire book. I really liked how the Vietnamese outworkers you focused on were situated within a lineage of migrant workers, tracing Australia’s migration histories. You mention that there were Jewish immigrants, Italians, Greeks, Chileans, Lebanese, Eastern Europeans, Vietnamese in the 70s and 80s, followed by the Chinese, Cambodians, and Thais. You’ve placed this history alongside research about the legislated erosions of protectionist policies within Australia for the manufacturing industry, and you use the term “shadow force” to describe the rise of outwork until it declined at the turn of the new millennium. I’m wondering what was it about this particular dimension of the story that compelled you to weave it within the project?

Emma Do: I wanted to convey that there were larger forces (economically and politically) shaping their lives and decisions. I think for the reader, I wanted to give them this context because this exploitation and these conditions in the labour market don’t just happen because of one lone actor but because it’s a whole environment that is encouraged or discouraged by economic policy in the country. I wanted to set the larger scene and then zoom into the effect that that could have on people at the day-to-day level. That was really important to me. Otherwise, you’re just reading personal stories without the context, without the political context.

James W. Goh: Finally, what would you both like readers to take away from the book?

Kim Lam: At the heart of it, we wanted to create something ‘for us’—for second generation Vietnamese Australians. To deliver a deep sense of belonging to this very specific community. It’s been very special to hear that many people have been able to experience the project in that way.

Print publications are surely a community love-language. I want the mere existence of this book to signal that your story is worth telling, that there is space for your history, culture, memories.

Emma Do: I think also to the fashion community: to treat makers with respect and to understand their stories, where they came from, and what they’ve gone through to get to this point. There is a language barrier that might prevent people non-Vietnamese people from knowing these stories. If you are a fashion designer here and getting the services of a Vietnamese maker, you might not get to understand their personal histories.

When I was talking to people who worked in factories and outworkers and such, they would say, “Oh but you know. Young people come in, and they say they’re a designer, but they don’t show respect or understanding for my work. They don’t know what goes into what I do. They have their demands and then expect it to be done this way.” From talking to people in the industry, I can understand this divide. Designers are really well-respected, lauded in society, and put on a pedestal (everyone’s like, “Ooh. I want to be a fashion designer”) but people don’t respect the “dirty work,” I guess, of making clothing.

Another aspect I want people to come away with is clothing is very human and not just churned out by machinery.

I want people to think critically about labour as well. I see a lot of parallels between what’s happening in the gig economy right now with outwork. It’s the same discussion playing out: whether Uber drivers should be classified as contractors as employees—that’s the question that was debated in regard to outwork decades ago (in the end, laws were put in place to make sure outworkers were treated as employees). I didn’t say this explicitly in the book, but I do want people to draw that parallel and recognise other forms of precarious labour that exist and continue to exist.

You can order a copy of Working From Home / may ở nhà from mayonha.bigcartel.com. Emma and Kim are currently working on a Vietnamese translation of the book. For further updates about the project, you can follow @may_o_nha on Instagram.

Contributors’ Bios

James W. Goh writes from Dharug land in Sydney. He is interested in histories of empire and understanding how colonial presents are reproduced.

Emma Do is a writer and editor based in Narrm (Melbourne). She is currently the editor of frankie magazine, and is (re)learning Vietnamese in her spare time.

Kim Lam is a Vietnamese-Australian illustrator, comics artist and writer living and working in Naarm. Her works explore innocence, agency and death, often in blue. Alongside her arts practice she works as a veterinarian, which directly informed her canine afterlife comic ‘Good Boy’. She lives with hypergraphia and a cat named π.