Where is the beginning and where is the end — of memory? of grief? of youth? Susan Nguyen’s debut poetry collection Dear Diaspora explores these questions by leading us through a girlhood steeped in loss and longing. In a series of interconnected poems that read like a kaleidoscope of memories, Nguyen’s protagonist Suzi grapples with finding her place in the Vietnamese diaspora after the loss of her father. She makes lists of questions, conducts Google searches, and writes letters to the diaspora. In this excavation of her past and present, Suzi steps from the greenness of childhood into a new awareness of who she is.

Similar to Susan (and Suzi!), I also grew up in the 1990s and early 2000s in America and was thrilled to read a book of poems that so deftly conjured the mood of what it was like to come of age during that time. After her book’s publication in September 2021, Susan and I met to talk about her research process, literary craft, and journey as a writer. Susan also shared her thoughts on our generation’s role in uncovering our families’ histories, as well as tips on how to read poetry.

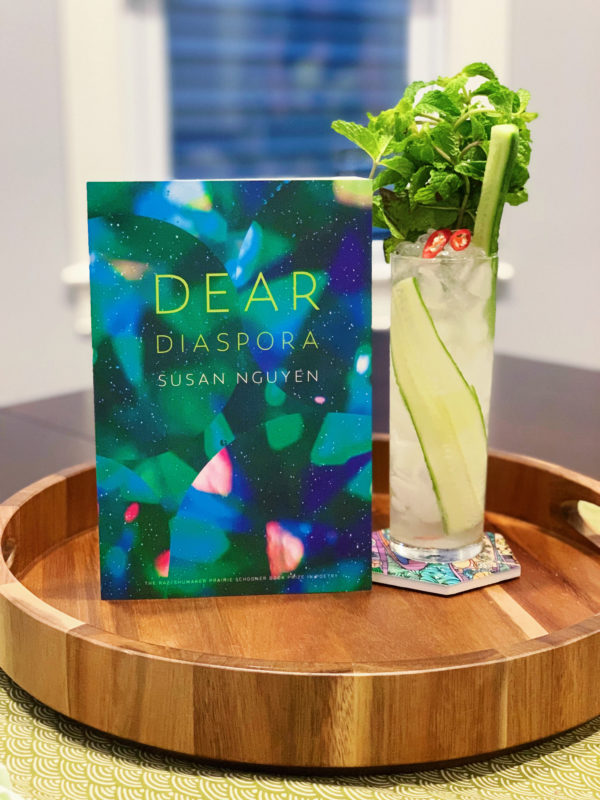

To celebrate the release of Dear Diaspora, Susan and I co-created a cocktail pairing for her book. The recipe for the “Dream of Green” cocktail is a spin-off of a mezcal mint julep that incorporates greenery through the use of mint, cucumber, jasmine tea, and lime. With a touch of fish sauce and chili pepper, when paired with the fresh aroma of mint and cucumber, this drink will evoke memories of homey Vietnamese dishes like bánh xèo, bún chả giò, and bánh cuốn.

Cheers!

~

Thuy Phan: How did you start writing? When did you know that you wanted to be a writer?

Susan Nguyen: For as long as I can remember I’ve always wanted to be a writer. I always thought I was going to be a novelist because I spent a lot of time reading fiction when I was growing up. I took introduction to creative writing as an elective in college, and that was the first time I came to writing more seriously. (I actually didn’t spend that much time writing growing up, mostly reading and dreaming to be a writer.) In that intro to writing class, we did fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, and I realized that poetry made the most sense for me as a writer. With poetry, I felt like I had more freedom to experiment on the page. Poetry gave me a lot of room to play with fragmentation, which I didn’t feel like I could do at the time with prose writing.

Thuy: I love hearing about how you came to discover poetry! Because poetry is a challenging form—not just to consume but also to create.

Susan: Yes! And while I may have an MFA in poetry, I will be the first to say that poetry is so hard! Although reading poetry is still challenging for me, I’m not trying to run away from it. If it’s a difficult poem, I think, “Let me spend some time with this, and if I’m having a difficult time accessing it right now, I can come back to it later and that’s okay.” It can be frustrating and difficult but there’s also an excitement to it now, whereas before I felt like I was going to shut down because I didn’t get it, you know?

Thuy: Following up on that, do you have tips for readers on how to read poetry?

Susan: Read widely, not just within poetry but across different genres. This helps because you’ll be exposed to more, and reading widely opens the door to help you see what is possible in writing.

Also, it’s okay to not completely understand a poem the first time you read it. The first time I read a collection, I’m not reading it to understand everything, but I’m reading it to experience what stands out to me, in terms of imagery and emotions. Poetry is not always necessarily about a literal interpretation, but the feelings the author is trying convey, express, or evoke through language. Instead of asking, “Did that actually literally happen?” I’ll reframe the question as something like “That was a surprising move – what was the author’s intent behind that?” The great thing about poetry is that you can come back to it later and realize you’re seeing something different!

Thuy: That’s really helpful advice. Now, let’s talk about your book, Dear Diaspora.

What was your process of connecting all the different pieces in your collection together to create Dear Diaspora?

Susan: I started with writing first-person poems, but for some reason, I was having a really hard time writing about childhood and adolescence. I was being very narrative, but not in a good way. I was trying to explain or get the exact truth down, and I was just getting in my own way. So, I decided to write third person poems about Suzi, a fictionalized version of myself. I drew from my lived experiences, but now I wasn’t concerned about what exactly happened. There was now more room for me to play and imagine, and that really opened a lot of doors for me to write about the girlhood aspect of diaspora (and my own very specific experience of girlhood in the 1990s and early 2000s) that I wasn’t able to do in my first-person poems. At first, I thought my whole book would be a collection of third-person, prose-block poems. My mentors helped me realize that my book didn’t have to be an either-or choice between the third-person poems or first-person poems. I reordered the book so many times and chose to interweave the poems, to show Suzi in a more in-depth way and make it a more interesting experience for the reader.

Thuy: What was your research process like?

Susan: A lot of my research involved reading old archived newspaper articles from the late ‘80s and early ‘90s about the boat people. (And that’s when my immediate family arrived, in the early ‘90s.) During grad school, I also had a fellowship from ASU that allowed me to visit my family in Virginia and do an oral history project. I interviewed my parents and a few other relatives. Besides that, I took three years of Vietnamese language courses during my MFA. In those classes, I got to learn a lot about Vietnamese folklore and mythology, which shows up in the collection. I also drew from memory and lived experience to create the atmosphere and mood of the 1990s and early 2000s in my poems. Reading more books by Asian American Pacific Islander writers in a contemporary AAPI literature course in grad school also helped. All of these activities provided me with the background knowledge that I didn’t have of Vietnam, the war, and its aftermath, leading me to write the book that I ended up writing.

Thuy: The epigraph of your book includes a quote about reckoning with memory from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee. What are your thoughts on our generation’s role in unpacking and uncovering history as well as inherited memories from our families?

Susan: I can only speak for myself about the responsibility I feel. Memory is so important. It’s easy to forget or want to forget certain things, but not knowing parts of my family history feels like not knowing a part of my own identity. I didn’t know much about Vietnamese culture and history, or even how my family came here to the US. In one of my poems, I mentioned how one of my uncle’s Church sponsors comes every year on Thanksgiving. For a long time, I thought that he was just a nice older white gentleman. No one’s ever told me why he was always there. But when I got older, I finally understood why because I thought to ask.

It’s important to ask about your history, but it’s also important to remember that family doesn’t owe you anything, especially if things are painful or if they don’t want to talk about it. But I think we owe it to our families and our future survival to ask these questions and get these histories down (if our families are open to sharing). I also have older family who came here first, and once they go, their stories will probably go, too, if no one is there to write them down for the younger generations. There is a grief that comes with that…with things that get lost.

Thuy: There’s also a lot of trauma and grief to hold on to in these memories. How can we treat these inherited stories and memories with care?

Susan: Part of my experience of being a writer is wanting to honor that memory. It shows up in my writing and my art because I want to preserve some of that. I’ve also come to the understanding that there will be things that will remain unknown. Memories will always be lost. I’m preserving what I can. In my book, there are a lot of things that are imagined and invented, too, because it’s poetry and not nonfiction. But it is a true experience for me in terms of delving into and preserving my family history, even though some of it is not the truth to a T, but maybe it is the truth for me, the writer.

Thuy: What you’ve said reminded me of T Kira Madden’s essay, “Against Catharsis: Writing is Not Therapy,” in which she compares the role of the writer to that of a magician pulling an invisible thread to perform a magic trick, to make the audience believe. So it’s not really about telling THE literal truth, for example, what exactly you were doing or wearing that day. But our job is to craft the memory in a way that the reader can project themselves onto the narrative, fill in the blanks, and see their own memory reflected back through the writer’s story.

Susan: Yes! And that’s where I felt like I really got hung up. And that’s why Suzi got invented—to get me to this point in my writing because that’s where the hang-up was.

Thuy: That’s such a great literary tool to get yourself out of that writer’s block.

Susan: I think everyone should try it, even if that’s not what the end result of your work will be. Changing form can help you step outside of yourself a little bit, as well as step outside of your comfort zone as a writer, whether it be changing from first person to third person or second person.

Thuy: Do you have any tips for people of our generation on how to start asking questions and having conversations with their family members?

Susan: Yes! I did a bit of digging into online resources to understand what the process of conducting an oral history project would be like. It was also important for me to research the history of the Vietnam War so that I could have context, so that I wouldn’t be asking my family questions blindly. Doing some research beforehand is helpful because your family members may have stories that they may not want to share or memories that are painful to recall. It’s also important because your family might not be able to fill in all the gaps of your knowledge—in the end, I wouldn’t expect them to.

Thuy: Can you talk about the prevalent theme of greenery and nature in your poems? Are you a nature person?

Susan: I love nature! In my memories of times when I’m feeling happy, free, or at peace, I’m usually outside. Nature appears in my work because when I was thinking back to my memories of my growing up in Virginia, the thing that sticks out is nature. The color green serves as an access point to the memory-scape and landscape of my childhood. I’m really drawn to having readers construct imagery in poetry, so I often draw from nature when I’m working on a metaphor or imagery. I also leaned into my poetic obsession with the color “green,” which reappears a lot throughout the collection. In the past, I would have been self-conscious of using the same word twice within the same poem. But now, I’m leaning into the obsession to see what comes out of it.

Thuy: I especially loved the lines in which you wrote about the “green light of morning.” That was so lovely. Another beautifully rendered thing in your collection is your portrayal of a girl’s desire with her feelings of grief. Can you tell us more about your choice to juxtapose desire and grief in your poems?

Susan: I have to give credit to a class on grief and ecstasy that I was in with Natalie Diaz. In that class, we read about and discussed the line between grief and ecstasy—if even such a line exists. I was thinking about it so much that it kept popping up in my poems. Just like the color green, I decided to lean into this obsession. In terms of the juxtaposition: when I’m thinking about diaspora, I think about the grief and sadness for things that have happened (or didn’t happen) or things that have been lost. But there are also pockets of joy. I thought about my own experience growing up in the diaspora, finding joy with what I had and where I was as a kid. The third-person Suzi poems helped me bring these themes in.

Thuy: Who is in your artistic lineage? (They can be any artist, living at any point in time.)

Susan: Ocean Vuong and Cathy Linh Che. I also want to give a shout out to other Vietnamese American authors because it was always helpful to see someone else who’s Vietnamese American, to see that it’s possible, and to see myself in their writing, even if it’s not the same exact experience. It pushes me to write that book for myself, the one that I wanted to read, because I’m probably not the only one who wants to feel seen.

Thuy: For all the emerging writers who may be reading this now: what advice would you give to your younger self who dreams of becoming a writer?

Susan: Read as much as you can. Even if you don’t have it in you now to write that poem or prose piece that you want to write, reading diversely and widely—in terms of authors and genres— always serves as good inspiration. It’s okay if you don’t find exactly what you’re looking for because maybe you can write that book yourself.

~

Dream of Green

ingredients:

2 oz mezcal

4-5 slices of cucumber

1/2 oz freshly squeezed lime juice

1/2 oz strongly brewed jasmine tea

~1/2 oz honey chili fish sauce syrup

(To make this syrup, combine 1/2 oz honey, 1/2 oz hot water, 5-6 thin slices of Thai chili pepper, and 1-2 drops of fish sauce, and stir until the honey dissolves. When making this syrup, add the fish sauce one drop at a time, and add more to taste, as needed.)

*garnishes: mint bouquet (4-6 sprigs), long cucumber wedge, generously slices of Thai chili pepper

- In a steel tin or tall glass, muddle cucumber, and strain out the muddled cucumber, leaving behind the juices only.

- Rub the interior of the tin/glass with the mint bouquet to release the herb’s aromatic oils. Do not crush any of the mint leaves because this will result in a bitter taste.

- Add mezcal and approximately 1/3 oz of honey chili fish sauce syrup to the cucumber juice in the tin/glass, and stir gently with a bar spoon.

- Fill half the tin/glass with crushed ice, and stir for about 10 seconds until the outside of the tin/glass is frosted.

- Add lime juice and jasmine tea, add more crushed ice until the tin/glass is about 2/3 full, and briefly stir.

- Fill the rest of the tin/glass with crushed ice, until it’s heaping. Firmly pack the ice into the tin/glass to prevent rapid melting.

- Add the mint bouquet and a long wedge of cucumber for garnishes. Drizzle approximately 1/4 oz of the honey chili fish sauce syrup over the ice, and top with 2 thick slices of chili pepper. Enjoy with a straw!

Contributors’ Bio

Thuy Phan is an HR professional, writer, dancer, and creator of @mixaphoria on Instagram, where she reviews books and pairs them with craft cocktails. She is currently working on a collection of personal essays on family, estrangement, race, and the diasporic experience. Thuy was born in Vietnam, raised in the US, and currently resides in Somerville, MA.

Thuy Phan is an HR professional, writer, dancer, and creator of @mixaphoria on Instagram, where she reviews books and pairs them with craft cocktails. She is currently working on a collection of personal essays on family, estrangement, race, and the diasporic experience. Thuy was born in Vietnam, raised in the US, and currently resides in Somerville, MA.

Susan Nguyen hails from Virginia but currently lives and writes in Arizona. She earned her MFA in Poetry from Arizona State University, where she won the Aleida Rodriguez Memorial Prize and fellowships from the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing. In 2018, PBS NewsHour named her one of “three women poets to watch.” Her work appears in diagram, Tin House, and elsewhere. She writes a lot about identity, the body, and the Vietnamese diaspora and also likes to make zines. Her debut collection, Dear Diaspora, won the 2020 Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry and was published by the University of Nebraska Press in September 2021.

Susan Nguyen hails from Virginia but currently lives and writes in Arizona. She earned her MFA in Poetry from Arizona State University, where she won the Aleida Rodriguez Memorial Prize and fellowships from the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing. In 2018, PBS NewsHour named her one of “three women poets to watch.” Her work appears in diagram, Tin House, and elsewhere. She writes a lot about identity, the body, and the Vietnamese diaspora and also likes to make zines. Her debut collection, Dear Diaspora, won the 2020 Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry and was published by the University of Nebraska Press in September 2021.