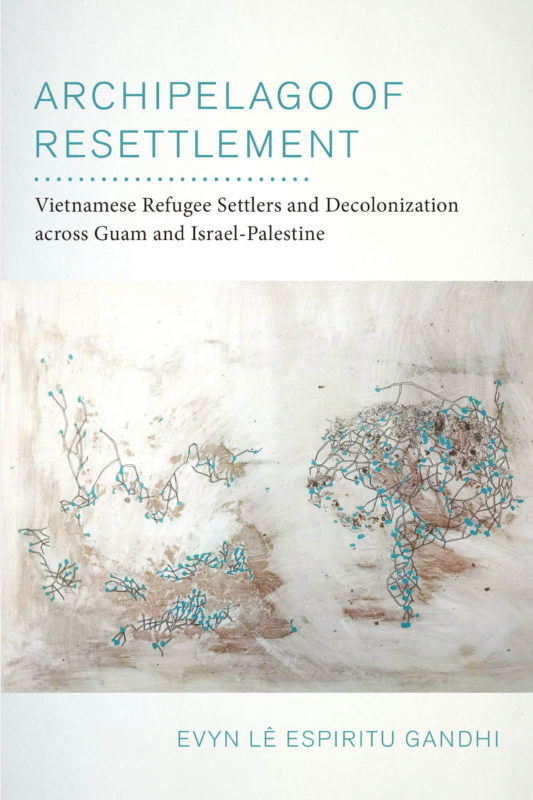

Examining the connections between Guam, Vietnam, and Israel-Palestine, Evyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi engages in what she calls “archipelagic history,” tracing “connections between spaces on the seeming margins of grand historical narratives in order to draw attention to South-South relations.” Archipelago of Resettlement moves between historical and cultural analysis, rejecting the constraints of positivist approaches to social sciences. Guam, the nonfigurative island, is part of a triadic archipelago when joining Vietnam and Israel-Palestine, the metaphorical islands. What keeps them together while distant is nước: the water that Vietnamese refugees needed to cross in 1975, after the fall of Saigon, to reach Guam, which became the main processing center established by the US government for the incoming Vietnamese before most of them moved to the mainland.

In 1977, a group of 66 stranded refugees were saved by the crew of the Israeli cargo ship Yuvali along Vietnam’s cost and would be welcomed to Israel by the country’s newly inaugurated prime minister, Menachem Begin. Two further waves of refugees arrived at Israel later on, reaching a total of around 366 refugees. The arrival of Vietnamese refugees to Israel was historical, as they became the first non-Jewish group to be naturalized as citizens. However, in her analysis of Israel’s decision to accept Vietnamese refugees (based on newspaper articles, Israel State Archives (ISA) documents, and interviews) Gandhi convincingly demonstrates that Begin’s move “should be read as a performance of humanitarianism intended to recuperate Israel’s image in the international sphere.” In a testament to the success of the Israeli prime minister’s decision (at least in terms of public relations), Begin’s example continues to be invoked in present times to argue in favor of accepting Ethiopian or Syrian refugees into Israel. From the group of 366 refugees who were accepted into the country, around half of them continued to live in Israel with their descendants by 2015, according to the Vietnamese Embassy in Tel Aviv.

Almost three decades after the expulsion of 750,000 Arabs in an ethnic cleansing campaign against Palestinians, Israel intended to demonstrate that it could be not only a refugee maker, but also a refugee taker. In the process, however, the new Vietnamese Israelis became unintentional accomplices in the Zionist settler-colonial project that produced the Palestinian Nakba (catastrophe in Arabic). It is indicative of the contradictions of Vietnamese refugees’ experience in Israel that the second wave of refugees to reach the country were hosted in Afula, a Zionist settlement town that had displaced the Arab village of Al-ʿAffūla. Those Vietnamese refugees who decided to stay in Guam after being evacuated to the Pacific island would also come to embody a dual identity, which Gandhi terms ‘refugee settler’: “non-Indigenous refugees who, due to resettlement following forced displacement, become settlers in settler colonial states.”

The history of Guam in the twentieth century is, similar to that of Palestine, one of Indigenous displacement and gargantuan demographic changes. Guam, whose geographical area is more than four times smaller than Delaware, hosts a military contingent of around 6,000 US troops, some of them accompanied by family members. The number could soon double if plans to relocate 5,000 US military personnel currently based on Japan’s Okinawa island move forward. In recent times, Okinawans have increasingly mobilized to prevent this, in a movement sparked by the pollution and noise of the US military bases, and, most importantly, the numerous cases of sexual violence and murder committed by US military personnel against Okinawan women.

Whereas Okinawa did not host US troops until the defeat of Japan in the Second World War, Guam has had an almost uninterrupted US military presence (Japan occupied the island from 1941 to 1944) since 1898. At that time, the Pacific island saw the United States replace Spain as the colonial power ruling Guam. The Chamorros, the Indigenous people of Guam, have suffered the consequences of US imperialism ever since, in a process of land dispossession that presents a direct threat to Chamorro identity, which is closely tied to their lands and water.

As Gandhi aptly explains in the book, Chamorros have long suffered from “settler militarism,” the unilateral overtaking of Indigenous lands for military purposes. The process started already in 1898, when the first US governor of the island forced the local inhabitants to register their lands by paying taxes. As most Chamorros could not afford to complete the registration process, the governor’s order led to mass land dispossession. Later on, the US government would absolve itself from the task of rebuilding the devastated villages left by the 1944 Battle of Guam. In present times, the US military controls around one third of the island’s surface area. The heavy footprint of the army, which has conducted massive construction works over the years, has led to considerable biodiversity loss.

When Guam became the epicenter of ‘Operation New Life’, by which more than 111,000 Vietnamese refugees were relocated to the United States after staying in the island, Guamanians displayed their hospitality, encapsulated in the Chamorro concept of inafa’maolek. At the same time, however, for the US ‘Operation New Life’ played a somehow analogous role to Begin’s acceptance of three waves of Vietnamese refugees. As Gandhi puts it: “The rescue of Vietnamese refugees during Operation New Life was co-constitutive with the ongoing displacement of Indigenous Chamorro people; the ‘conversion’ of US military bases in Guam into ‘places of refuge’ for Vietnamese refugees did not preclude the settler imperialist role these bases continued to play in securing US interests across Asia and Oceania.”

It is important to note that Gandhi’s description of the Vietnamese in Guam and Israel/Palestine does not present the “refugee-settler” as devoid of agency. As Yen Le Espiritu had written in Body Counts, the refugee is “not only a person vulnerable to wartime violence but also a living subject in a prime position to critique US imperial under-currents.” Gandhi thus expresses concern toward the fact that most Vietnamese in Guam are not interested in decolonization because “their US citizenship rights are predicated upon US jurisdiction over Guam.” Likewise, some Vietnamese Israelis worry “that if Palestinians were to regain sovereignty, they too would be expelled from Palestine, becoming refugees yet again.”

But the same agency that allows Vietnamese refugees and their descendants to embrace their “refugee-settler” condition can also be channeled in the opposite direction. People such as Bianca Nguyen, a Vietnamese American living in Guam who started The Decolonization Conversation blog in 2008 after becoming acquainted with the Chamorros’ history of land destitution, offer a source of hope and resistance. Gandhi thus ends her important book by calling for “archipelagic understandings of home,” as based on the strength of South-South connections, to “unsettle the settler colonial state, calling forth decolonial futures of radical multiplicity that facilitate more ethical forms of relationality between refugee settlers and Indigenous subjects.”

Marc Martorell Junyent is pursuing a master’s degree in Comparative Middle East Politics and Society at the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen and the American University in Cairo. His main interests are the politics and history of the Middle East, with area interests in Iran, Turkey, Yemen, Tunisia and Israel/Palestine. He tweets at @MarcMartorell3