To listen to Sinn Sisamouth is to have a romance with oneself.

At once, his voice is an apology, a call to marriage, a Friday night dance invite, cha-cha crooner, an accompaniment alongside Apsara Dance, a nostalgic warmth. Sometimes his voice enters a capella, followed by an accordion, a clarinet and it’s unpredictable what genre he’ll go into.

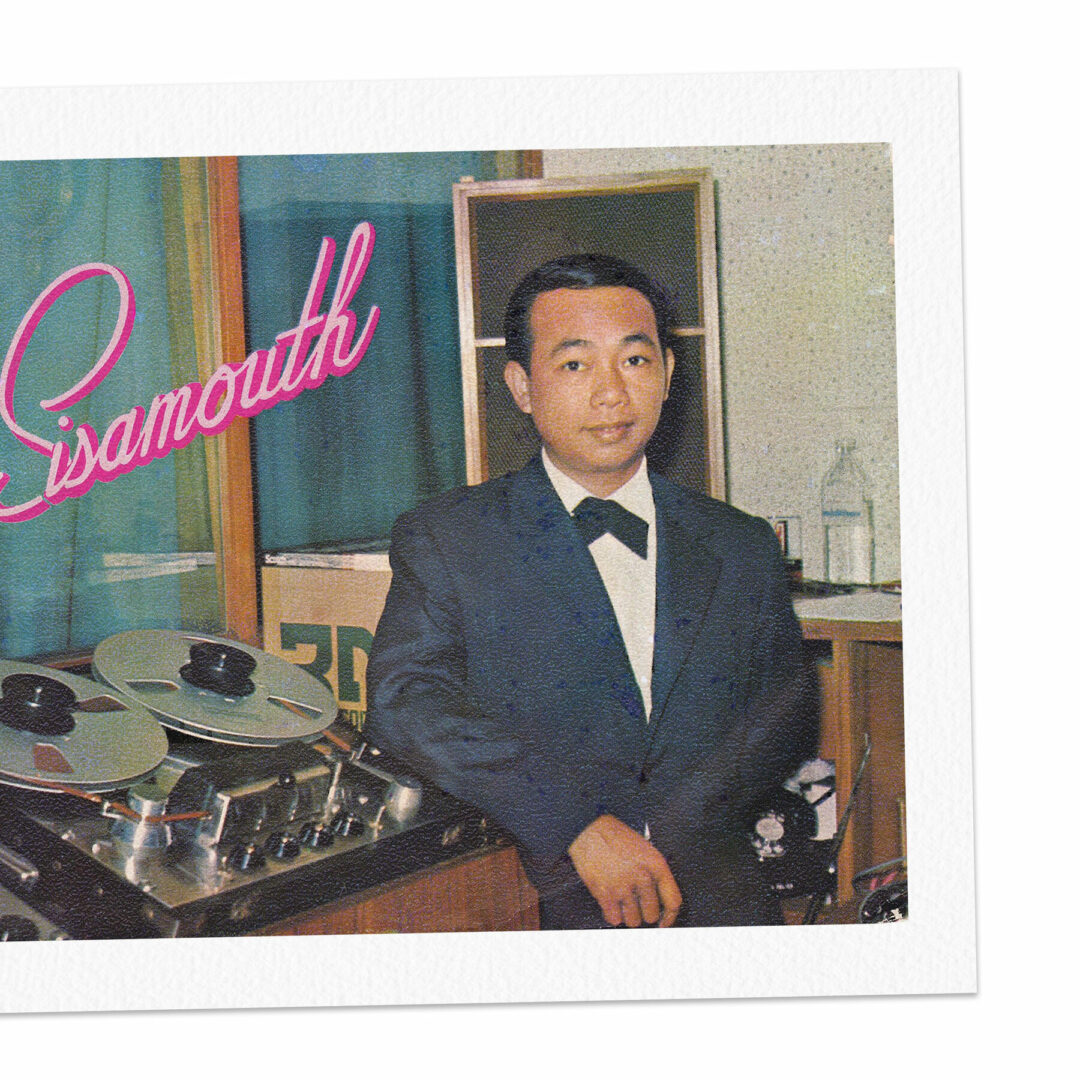

You give in to a tenor ringing across time, beyond regimes and generations. You hear him regurgitated, remixed, head posted on other photos, a cheap photoshop.

In a column called “Overlooked No More” in the New York Times, they had the nerve to claim him “overlooked,” something so absurd that I fume at not having something stronger than quotation marks to express this. The orientalist nature of this observation, when he was never overlooked by us, he who remains, as ever, in the present tense, by a generation hungry for connection to their elders.

I think of him as the singing uncle, the one who just has to sing karaoke with lyrics pulled up on his smart phone, but with a fedora. My man was dapper, dressed from head to toe ready to sing for the elite and powerful of Phnom Penh.

The only redeeming quality of getting COVID was my singing range extended by an octave and I could suddenly sing his “Champa Battambang” in the original key, though perhaps without the charm that he invokes through his deep, nasally vibrato (it makes me so heady) but to be that much closer to him through my own voice…

How many weddings have I attended and watched my mother (not my father, ever) do the lam leav or romvong? These circle dances where we congregate as a community, to remind us that we can still be together without being killed by those who resemble us, by those who are us, that some circles close but this is an opening and we keep creating life through commitments.

What do Google searches of him produce? Various spellings, musical collections, archival images and rare video. What about his disappearance?

I’m a teenager and we’re driving through Fordham Road in the Bronx when my father puts on Khmer music. Finally wrestling the cassette player from our preferred hip hop and Guns’n’Roses, he spells out the pronunciation, “See-sah-muot. He was the most famous singer in Cambodia.” That was my education, as much as you could get from a direct survivor of the Khmer Rouge.

Other forms of learning were via osmosis, coming across in the currents of our household as we lived. Dinner time was always announced by the sizzle of garlic against canola oil in the kitchen. That smell made our mother remind us to close the closet door, lest the smell permeate our coats and other fabrics. Then came the request for wedding music. What did my mother imagine when she listened to it? Why did she request it? Where did she go in her mind when Sisamouth’s voice permeated the air like the garlic? Is she thinking about her wedding day? Is she longing for a Cambodia that no longer exists? Whatever the desire, we facilitate it by putting in the specific CD into the player and turn on the stereo in the living room loud enough for her to hear in the kitchen.

Out of Long Beach, California, Golden Dragon Cambodian released volumes of VHS music videos with attractive young people lip syncing songs during the golden era (pre-Khmer Rouge). Permed, crimped hair for the women and thick hair cuts with little rat pony-tails and long trench coats for the men. How desperate my brothers and I were to watch anything that resembled what my parents experienced or heard when these songs came on. Where are the folks who look like us, in this world where every Asian is Chinese, where our language is just another kind of Chinese to onlookers? Typical of the style that was Khmer courtship and decorum, often a guy who is chasing a girl in gesture and dance, sometimes flamboyantly, with vocalizing that resembles Bollywood films (you can hear the Indian influence in the melodies) or even more Sino-style melismas. These guys with their tanks and shoulder-padded blazers a la Miami Vice were so cute and Khmer. I wondered if I was supposed to desire them, this romance. Is this how Khmers romanced each other? Never an actual kiss, but dancing around and within each other, most often a space in-between. There is appropriate touching, embracing, amorous but never vulgar as the lovers look gaze at each other somewhere in Southern California. I wanted this fairy tale that came with a whirling courtship and perhaps a side ponytail held up by a bright scrunchy. The stonewashed denim overalls seems a strange accompaniment to a Cambodian 60s duet.

There’s a certain grammar to the performance.

Nearly 42 and I’ve still never seen my father dance nor sing. He whistles though. And he can tap out a mean “Welcome to the Jungle” on the steering wheel. He promised me a dance at my wedding which never happened and which I realized too late. I don’t know how long I’ll wait. I learned to be embarrassed by the things my body could do, its movement and its sound. But that’s what we have our idols for.

There is no emotion, no situation, no occasion that Lok Tha Sinn Sisamouth didn’t have a song for with his prolific collection of songs.

Put on the record. Speak about him in the present tense. Teach. Cover him but don’t replace him. Sing ច្រៀង ច្រៀង ច្រៀង.

“Champa Battambang” by Sinn Sisamouth

Sokunthary Svay is a Khmer writer from the Bronx. A founding member of the Cambodian American Literary Arts Association (CALAA), she has received fellowships from the American Opera Project, Poets House, Willow Books, and CUNY. In addition to a published poetry collection, Apsara in New York (Willow Books, 2017), her first opera, Woman of Letters, set by composer Liliya Ugay, received its world premiere at the Kennedy Center in January 2020. Her second opera with Ugay, Chhlong Tonle, received its premiere in March 2022. She is a doctoral candidate in English at the CUNY Graduate Center.

Sokunthary Svay is a Khmer writer from the Bronx. A founding member of the Cambodian American Literary Arts Association (CALAA), she has received fellowships from the American Opera Project, Poets House, Willow Books, and CUNY. In addition to a published poetry collection, Apsara in New York (Willow Books, 2017), her first opera, Woman of Letters, set by composer Liliya Ugay, received its world premiere at the Kennedy Center in January 2020. Her second opera with Ugay, Chhlong Tonle, received its premiere in March 2022. She is a doctoral candidate in English at the CUNY Graduate Center.