Exhausted as Má may be from relistening to nhạc Việt Nam, she has yet to move on from the emotional strains she frequently hears whenever she places a CD in the Sylvania. I don’t think she can escape those memories retold through lyrics, some of which parallel to her experiences during and after the war.

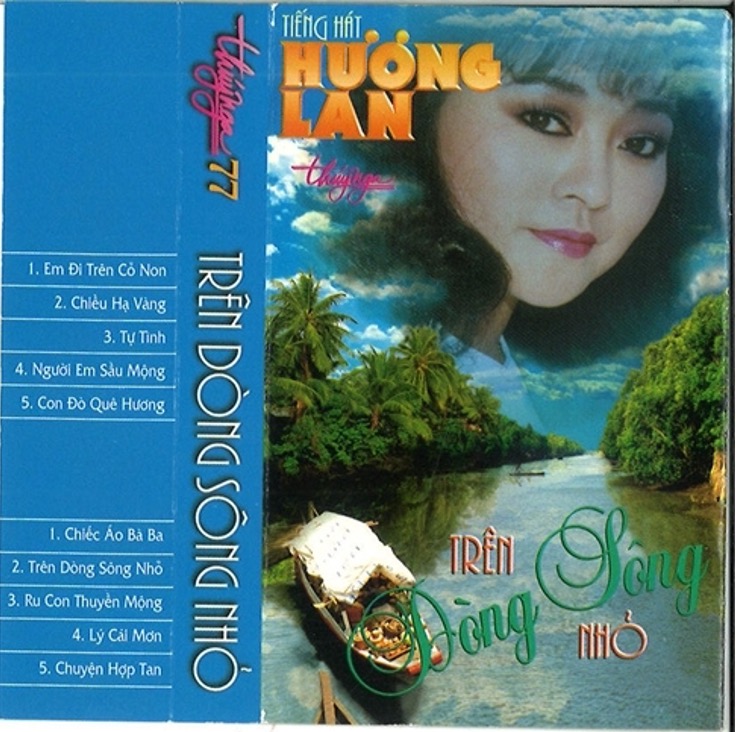

Perhaps a tired refrain amongst Vietnamese writers, which has since been recently critiqued, songs containing the words boats, sea, rivers, nautical narratives and themes, and the threats of pirates are inescapable images and memories, also becoming immutable, conjuring imageries in Vietnamese diasporic music. Reflecting on how Vietnamese songs necessitate perpetual relistenings, my mother admits with a weariness that feels uncharacteristic, considering the infinite energy she often exudes:

Relistening to any songs that allude to the sea provoke an intense sadness that I can’t convey in words. Any rivers that I remember submerging my body into in Việt Nam to catch fish or to swim become such a faraway feeling because it’s been years, but the familiarity of it all is still very present. Different songs, but they convey the same thing for most of us, những người tị nạn // refugees, which speaks about the devastating trauma of having to flee and survive the waters until the boats we were on reached somewhere safe, in a way that we knew we won’t get captured and persecuted.

As Má remembers hearing from others, several people lost their lives in the sea, another displacement that may be unknown. She further shares:

It’s a devastating memory to remember those willing themselves to survive only to chết tha hương // die in exile, especially before reaching the trại tị nạn // refugee camps. It’s a tragedy, to survive only to die. I don’t think I can ever forget those stories.

Shortly after her return to Fayetteville, Arkansas, after almost two years of being stranded in Delaware due to the pandemic in 2020, my mother and I recently relistened to Hoàng Oanh’s 2006 re-recording of “Mong Chờ,” composed by Xuân Tiên. Má remembered listening to Hoàng Oanh’s first recording during the pre-1975 era on the Đài Phát Thanh // radio station in Việt Nam. The outro’s verse nebulously references an image of a sailing boat that never looks back, an image threaded with urgent permanence illuminated in the lyrics that resurrects several of Má’s memories:

When I was in Delaware, visiting your brother and we drove past Maryland, I saw so many boats, some docked while others were smoothly sailing across the river. I don’t remember what song was replaying in my head, but the word thuyền resurfaced somewhere in my memory and it became an immediate association of our lives – your father’s, your Chị Hai, and mine. Your Chị Hai, who was only nine months old, was too young to remember the war, but I will always remember holding her tightly as the boats we were on sailed away from Việt Nam, a country she will never have memories of. It doesn’t even matter which song popped up, but any song or lyrics with the words thuyền and nước carry a different form and meaning for us living overseas.

Images of boats never hesitating to look back and just continuing to sail further is such a powerful but despairing diasporic refrain, even if overused to the point of beats sounding overly maudlin. Living in a reality interspersed with memories feels like an eternal dream, or a recurring nightmare that refuses to shatter even after waking up; for my mother, it’s both. If boats are a vessel that carries displaced memories as the water is a force that continues to drift while retaining those memories, when do they stop being misplaced in history? And, at what point can Vietnamese refugees, displaced through several movements after multiple relocations and resettlements, stop with their constant movements and slowly move ahead and forward? When will their plight of continual waiting in their anger and angst end? Sounds of dislocation become sounds of echolocation where inflections continue to be repeated to warrant multiple relistenings.

A different period of waiting // Pre-1975 “Mong Chờ”

Other musical genres that Má relistens to include cải lương or tân cổ giao duyên, an intermix South Vietnamese musical genre that combines modern music and traditional opera music. These are two genres I can’t find myself listening to because of my own ignorance and being unable to appreciate the histories and difficult vocal techniques that take years to hone. It’s mostly because I’m not a fan of listening to dramatic beats that carry on elongated beats to one singular song, showing a steady tempo transition of a shift of melodramatic emotions.

I appreciate your post, but I feel like there is so much generalization about Vietnamese music and its history. Try to appreciate the diversity of Vietnamese diasporic music, it’s definitely not “same,” nor is it all “nostalgic” or “nationalistic.” I think you there comes a point where one is so good at analyzing Vietnamese people academically that you end up guessing their thoughts and feelings and take away their agency.

Lynda Trang Dai is not a Trump supporter due to her loyalty to a past she didn’t live through. And Vietnamese refugee people have had a variety of different forms of music about love, loss, fun, and partying like every culture. Generalizing their music as same is akin to saying all rap music is just swearing about drugs and all pop music about breakups and sex.