Y-Danair Niehrah realized young that his father was one of the best storytellers in his life. In high school, he became interested in his heritage as a Rhade, one of the handful of ethnic groups from Vietnam’s central highlands that often self-identify by the terms Degar or Montagnard. Listening closely, Y-Danair started to write his father’s experiences down, and after adding research, at the age of seventeen he published a short fictional work called Homeland: A Vietnam War Story of the Montagnards.

I was elated to stumble upon this book and moved by the world it evoked of a Degar boy growing up amid war. Years later, I still find myself thinking about Y-Danair’s protagonist. For the first time, a Degar character was at the center of the story instead of what was more typical of literature based on this era: the crudely drawn tribesman with one or two lines in the shadow of a Vietnamese, French, or American hero.

As I have written, it can be lonesome as a Degar/Montagnard American writer. Thus, it felt miraculous to come upon Homeland and Y-Danair, who over the years, honed his craft as a writer and editor. I got in touch and the exchange that followed led to an amazing event where we got to chat about being Degar writers, in an unprecedented era of isolation.

We are thrilled about Y-Danair Niehrah’s debut on diaCRITICS and the chance to publish an excerpt of his historical fiction, My Father and the River.

– H’Rina DeTroy

***

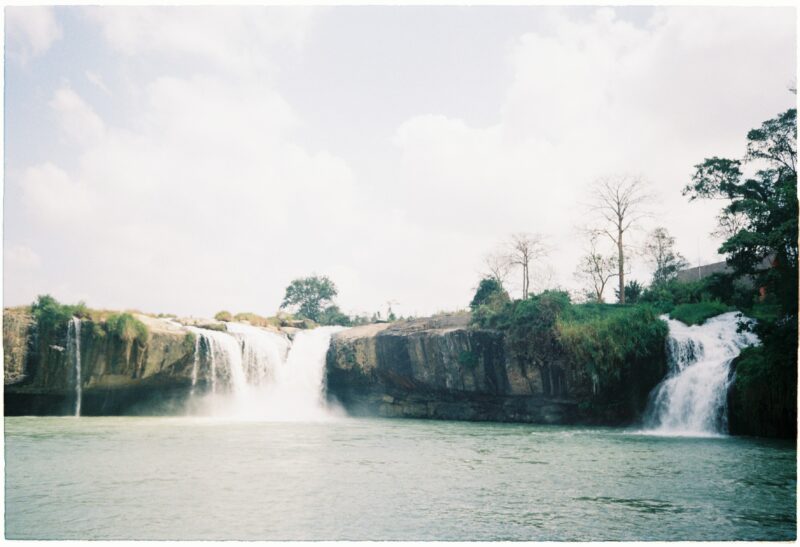

My father always called the rivers by Buôn Ale the purest water on Earth. The water flowed from the mountains in the west, down to the Srepok River that bordered Cambodia, forking into Ea Tam which rushed between evergreens that swayed like war banners in monsoon rain. We were going to row them to Ea Tam together soon, he’d say. I looked down. I was young enough to believe him then.

The river shimmered beneath the sun like gemstones, the sun began to set and I froze. A fear of heights was something the Buôn Ma Hduok boys conquered when they were younger than me. I brought my knees closer to my chest and looked over the edge, my stomach tingling. Their jeers grew louder.

“Don’t worry about them,” Yohan said, climbing up the rocks. Yohan had broad shoulders and stood a head taller than most his age. He placed my clothes on the rock beside me and nudged his head toward them. “They’re just messing with you.”

I looked away. It was easy for him to say. He grew up like the other kids—sitting on the backs of buffalos and swimming with river leeches. To them, I was the city boy. Spent most of my life in school in Buôn Ma Thuot. Yohan used to tease until he started to spend more time with the older boys training with Mike Force. He was thirteen, six years my elder, and like an older brother. He taught me how to shoot crossbows and place snares for rabbits—but I couldn’t explain to him why I felt scared to jump into the water, even if it was so pure. I imagined myself slipping from the rock, plunging down below. I took a deep breath.

“Let’s just go swim?” he said. The cheers and hollers continued. Some of the kids had taken to swimming or firing stones into the trees with slingshots. I wondered if they had forgotten about me up there, a bronze dot in the forest. I tried to still my legs from shaking. Even with Yohan there, I felt alone.

“Luin!”

Yohan and I jolted up to the sound of my father’s booming voice.

***

I followed my father down the cliff and jagged rocks, skipping to match his stride. The sun had dipped below the treetops and the air shifted to a muggy, calming cool when we reached a small riverbank beside Ea Tam, sand and dirt sloping smoothly into the mountain water.

“Are we going fishing?” I asked him.

My father shook his head. “Let’s talk, okay?”

We’d come to this riverbank a few times with Yohan and his parents—sometimes with village boys. Almost every time we’d come here, we’d wade into the river and catch the fish that would bottleneck near the bank. The few other times, some of the kids from Buôn Ma Hdouk would bathe or swim under the sun or moon, screeching and hollering louder than wild animals.

But never had I been here with my father. We sat down in the dirt and sand, him sinking into the ground up to his ankles.

“You’re sinking!” I laughed.

He managed to chuckle and patted his round belly.

The water swished against the rocks and bank. The sun was finishing its descent, painting the sky a red-orange that turned fluttering birds into black paint on the horizon. Insects danced and buzzed over the water, fleeing from hungry, croaking frogs. Fish weaved in and out between the river rocks, scales glimmering. I squeezed my knees to my chest and looked at my father.

He gazed over the water as if searching for beauty—blossoming orchids or gibbons swinging from low branches.

“I’m sorry we haven’t spent much time together these last few weeks.” He grabbed a stone nearby and threw it into the river. It skidded across the surface twice, then sunk.

“It’s ok,” I said.

“Your mother hasn’t told you everything.”

“She told me they took you to jail,” I said. “For helping … Bajaraka?” I recited those words the same way my mother did every other week when I had asked when my father was coming home. He had only been back in the village for a few weeks—at this point, prison may have seemed more like home. I was barely three when he was taken away by shouting men who held guns to my mother’s head and tore our home inside and out looking for documents. Now he was back, four years later, trying to pick up where he left off. The difference was that I was older and full of questions.

“She’s right. We aren’t in a good place right now.”

I turned to him, but he was still looking out over the treetops. “Why?”

“Lot of fighting going on—” he paused. “I just want you to know that every second I’m gone, it’s to make this country a better place for you to grow up in.”

I wanted to pull myself closer to him, but instead I sat still, stealing glances at my father as he looked over the river and trees. I grabbed a stone and skipped it over the water.

“So, are the Vietnamese bad?” I asked.

My father quickly said, “No—no Luin. No.”

“But they took you to jail—and we’re not bad.”

He sighed. “It’s complicated. Over time, your mother will have to explain more and more. But Luin—” and he looked at me, “What’s important is that you do not hold hate in your heart for anyone.”

Now, the river bubbled and flowed against the rocks, splashing on the riverbank.

“Be patient,” he said, as if he could hear my thoughts. “You need to understand what I’m about to say, okay?”

I nodded.

“Our people aren’t accepted right now, Luin. But you must not hate them for it. That’s not what we do. We love and we will fight to grow this country together, not apart.”

Midway through his sentence, my eyes darted to the river and a fish leapt out and back in, splashing with the current. My head moved with the fish as it swam out of sight.

“Pay attention,” he said, snapping me out of my fixation. “You have to understand.”

I paused. “Why?”

I wondered then if he even wanted to fish with me or take me hunting under the jungle canopy for rabbits or monkeys—teach me to handle wild boars or dogs. My name was lost among stories of prison or the resistance, our time shredded from his daily meetings and travels.

My father picked up a river stone and gripped it hard enough with the tips of his fingers that his nail beds were white.

“I’m leaving tomorrow morning,” he said. “To Buôn Sarpa.”

We had a few relatives out near Buôn Sarpa. My mother would always say we’d visit them soon when things were better. The way she described it always made it seem like it was mountains away.

“Can I come with you?”

He shook his head. “Not yet. Maybe in a few months when things are sorted out.”

“But you just came back,” I said. “You just came back.”

“It won’t be long, Luin, I promise—okay?”

“You just came back and we haven’t even spent a whole day together!”

He cleared his throat again and grabbed my shoulder. “I promise, it won’t be long. Soon you can visit.”

I crossed my arms. “Does Mom know?”

He nodded. “Let’s get back home. She’ll kill me if we miss dinner.”

We made our way back to the village in silence. We passed evergreens, flowers whose colors were muted by the blue of the coming moon—the only noise being the rumbling of the river that followed us home.

***

Buôn Ale was one of the larger villages on the outskirts of Buôn Ma Thuột, crowded with foot traffic. Some people were passing through to head to Buôn Ma Thuot, others were village folk. Longhouses and modern French villas stood together in the mixed suburb. The longhouses were built from bamboo and logs and straw, with steep wooden steps to climb that opened to a large space where families congregated in. Many of the French homes on the east side of the village were occupied by missionaries, some French, and more recently, Americans. Some richer families had jeeps or trucks parked outside of their homes. Others had motorcycles and bicycles standing against the wooden stilts of longhouses or propped up on the front porches. Villagers greeted us on the way in, some trying to strike up serious conversations with my father, but he waved them off and shook his head, and told them he’d catch up with them soon.

Our home sat two stories tall, tinted a dark beige. My father’s motorcycle leaned against the building under the living room window on the outside. He’d take it in and out of the city but recently started saying the tires would give out soon if he kept putting on weight. To my surprise, a forest green jeep with large, thick tires sat in the front yard. An American flag stuck up from the right front bumper, and a spare tire rested on the back.

“Who’s here?” I asked.

“A friend.” My father walked through the front door and I followed.

Our home smelled strongly of fried fish and onion. Black and white pictures hung on the hallway walls. Some from when I was born—ami always marveled at how fat a baby I had been. Plants filled every corner of the house, some as tall as the walls themselves, others resting gently on a windowsill. Besides weaving and selling clothing, my mother worked on gardening and selling plants most days so she was good at keeping her greens alive—she would tell me that my father, on the other hand, would never water plants and he’d wonder why they shriveled up and died. A few pots had errant flowers or smooth stones from the river resting beside the plants that I’d bring home from the forest. Mother even used to keep weeds if I thought they were something special. She loved orchids and kept some in my father’s office despite his protests. He’d complain they made his allergies flare up, but he confided to me the other week that he didn’t like how the flowers took away from the scent of the leather chair he had had since before I was born.

My father went down the hall to his office and I heard two muffled voices through the wall as I slipped into the kitchen. It was a small room and looked even smaller when my mother had plates and pots strewn over the counters and table.

She was hunched over the stove, stirring djam trong with a wooden spoon. I didn’t like the way my mother made it—she’d mix too much spinach with the eggplant and half the time, it was a battle to not spit it out. Regardless, it was as much of a staple in our diet as coffee. Fried fish sat on a paper-towel-covered plate to soak up the oil. She wore a stained, off-white apron like armor.

“Hi, ami,” I said and sat on a stool next to the counter.

“What took you two so long?” my mother said. She glanced out into the living room. “Your dad is in trouble—making me reheat all of this. And the fish is all cold now.”

“We were at the river,” I said, grabbing a small eggplant from a wicker basket and spinning it around on the countertop. “He told me he’s going to Buôn Sarpa.”

“Luin, put that back,” she said. I returned it to the counter and she added, “I know. You have to understand that your father is doing the best he can.”

“I know,” I said. “Do you think I could go, too?”

“School starts soon, you know that.” My mother turned around and set the spoon down on a small rag. She forced a smile, which she was much better at than my father, wrinkling the skin around her baggy eyes. “He loves you.”

“I know,” I repeated.

My father and his friend walked into the kitchen. His friend towered a head above my father but was twice as skinny. He was cleanly shaven with dark brown hair and had green eyes that matched his uniform with decorative pins against his jacket. When he walked, his shoes thudded against our wooden floorboards like thunder.

“Luin, this is Lieutenant Ashford,” my father said.

I fidgeted around in the chair and the man stuck his hand out at me.

“Your father told me a lot about you,” he said in broken French. We shook hands—smaller than my father’s, but he gripped with a commanding force.

“He and I will be going to Buôn Sarpa together,” my father said to me.

“Where is your green beret?” I asked.

“Smart kid.” The man grinned at my father.

“Smartest one in his class,” my mother said.

“Is that so?” the man said. “Now, Luin, I don’t have a green beret with me today but—” He reached into his pocket and pulled out a large silver coin. He nudged toward my hand and I stuck it out. He plopped the coin down onto my palm and smiled. “I brought this coin—it’s all yours. Keep it.”

I flipped the coin between my fingers, feeling the grooves in the metal. On one side, there was a chubby man with long, flowing hair like mine—though the top of his head was bald like my father’s—and on the other side, a large bell.

“That’s Benjamin Franklin,” he said. “And that’s the liberty bell. Keep it, keep it.”

I grinned and looked up at him. “Can I come to Buôn Sarpa with you and Dad?”

My mother sucked her teeth. “Luin, say thank you.”

“Thank you,” I mimicked, and put the coin in my pocket.

He and my father exchanged impassive looks, and the man said, “You need to stay here and be the man of the house while your father is gone.”

“He’s right, Luin,” my father said. “When I am gone you have to protect the village—but remember, you still have to listen to your mother.”

I expected my mother to laugh, but instead, she turned back around to move the pot of djam trong off the heat.

The man turned to my father and said, “Got everything ready to go?” My father nodded.

“I do,” he said.

“I thought you were leaving tomorrow,” I said. “You said earlier you were going to leave tomorrow.”

“Not staying for dinner either?” My mother asked, crossing her arms and leaning against the counter.

“They need us down there in the morning,” my father said. “We should leave here soon.”

I looked at my father, but he just stared at my mother until his gaze dropped to the floor. Soon, he retreated to his room and brought down a large suitcase. He said something to Mr. Ashford, and the man walked outside.

I remember this the way I remember killing my first boar—as vividly as the day Yohan told me he killed his first man.

Mother put her hands on the counter and barely turned when my father came to kiss her on the cheek to say goodbye. Said her name in a hushed whisper, and she reluctantly kissed him back.

“I’ll let you know when it’s a good time for you both to visit.”

She nodded before nudging her head toward me.

When he turned to me, I hopped off the stool to hug him and my chest grew tight as if I had leapt from the top of that same cliff and was plunging down into a bottomless river. I wrapped my arms around his big belly and he wrapped his arms around me.

“Be safe … and keep your mother safe, alright?” he said. “I won’t be gone long. I promise. When you visit, you might even be able to shoot some guns with the other boys.”

I managed to smile and told him, “You have to keep your promise.”

He let go and knelt down so that looked me in the eyes.

“If you miss me, think of mountain water.” His voice shook. “I’ll be on the other side of the Srepok and there will be nothing I want more than to come back here and row out onto Ea Tam with you.”

I nodded and grinned. “And teach me how to skip stones.”

“And catch more fish than Yohan.” He winked and smiled, hugged me one more time, and kissed me long on my forehead. When he stood, my mother wrapped her arms around him and they kissed.

I watched him walk down the hallway, seeming to stop at each picture on the wall for a moment and the potted plants along the way. I wondered what it would be like to go with him. To walk barefoot through the thick jungle down south and to row a boat together through the Srepok River, so wide I wouldn’t dare try to swim. I wanted to yell at him, scream and tell him to take a picture of me and mom against her blossoming plants with the pots brimming with forest flowers and river stones.

Instead, he slowly walked out the front door and gently pushed it shut.

My mother sat down and pulled me up onto her lap. We listened together. Heard the roar of the American jeep as it came to life, and smelled the gasoline as it shot through the air. We sat still to the whirr and sputtering as the noise became quieter and quieter, until finally, all that was left was the chirping of crickets, the pale blue of moonlight through the windows, and the scent of cold, fried fish.

Born and raised in Charleston, SC, Y-Danair Niehrah has studied creative writing since his father introduced computers to the family. He grew up reading genre fiction and horror but shifted to historical fiction in high school, focusing on the stories of the Degar people—the indigenous tribes of Vietnam. He studied creative writing at the College of Charleston under fantastic writers and mentors like Bret Lott and Anthony Varallo before pursuing an MFA at Queens University of Charlotte studying under writers like Fred Leebron, Naeem Murr, and Jonathan Dee.

Born and raised in Charleston, SC, Y-Danair Niehrah has studied creative writing since his father introduced computers to the family. He grew up reading genre fiction and horror but shifted to historical fiction in high school, focusing on the stories of the Degar people—the indigenous tribes of Vietnam. He studied creative writing at the College of Charleston under fantastic writers and mentors like Bret Lott and Anthony Varallo before pursuing an MFA at Queens University of Charlotte studying under writers like Fred Leebron, Naeem Murr, and Jonathan Dee.

Outside of the writing bubble, he’s a martial arts fanatic and has played drums and bass guitar for over fifteen years. He splits the rest of his free time experimenting with Texas- and Carolina-style barbeque and Italian/French cuisine.

I have read Homeland by Y-Danair B Niehrah and found it fascinating and well written and liked this short story too. In 1966/67 my wife Judy and I lived in DiLinh, Lam Dong province, and worked with the Koho refugee population that had been resettled from their mountain villages because of the war. We were with Vietnam Christian Service – as nurse and social worker. It was a profound experience that affected us for the rest of our lives. We made one visit back in 1998. I have just written a short story featuring a Koho boy as a kind of representative of the Koho story of that period. I am aware of the risk of cultural appropriation, but trying to be as empathetic as possible, as we also experienced some of the fear of the war and observed and got to know Koho individuals and in some ways tried to identify with them as they experienced war and displacement. I would really appreciate it if one or both of you would be willing to read it and comment, H’Rina de Troy or Y Daniar Niehrah. I realize that you both are more accomplished writers, but this is a story that has been inside of me for more than 50 years and wanted to write it.

Hi, Jerry,

This is Y-Danair. Sorry for finding your comment so late. I’d love to read your story! You can send it to me at [email protected]

My dad was raised most of the time through the Christian & Missionary Alliance so missionaries played a huge part in his life. Let me know if you have any questions!