A poem in Lan Duong’s new book, “Nothing Follows,” describes a scene you would not see in any Hollywood movie about the Vietnam War and its aftermath.

It’s the early 1980s and the San Jose-reared author, then a young girl, accompanies her father, a former lieutenant colonel in the South Vietnamese army, to the main public library. Duong is expected to read while her father finds other men to challenge in games of chess. That’s his way of decompressing. Once from a privileged class, her father works a patchwork of low-wage jobs to support the seven children he brought with him to California after the 1975 fall of Saigon.

“At the library, I read to master the words of a language he can barely speak,” Duong writes in the poem, “Cloud Anchor House.” She also finds the sexually explicit passages in adult fiction that will shape her views on sex and recognizes expletives she’s seen on bathroom walls, sometimes to blast immigrants like her who “are taking over San Jose.”

All the reading, she says, eventually helps her become an academic and a writer who tells provocative and painful stories about growing up a poor refugee girl in San Jose. These stories are brought together in Duong’s debut poetry collection, which offer a unique view of a momentous time in Bay Area history, when San Jose became home to the largest concentration of Vietnamese people outside that Southeast Asian nation.

An estimated 100,000 Vietnamese live in San Jose — more than a tenth of the city’s population. From 1975 through the 1990s, hundreds of thousands came to the United States to escape communist persecution and re-education camps. Many were attracted to warm-weather areas like Orange County and San Jose. Silicon Valley’s booming tech industry offered the additional draw of manufacturing jobs and the hope of upward mobility.

The arrival of so many Southeast Asians reshaped the landscape, with Vietnamese enclaves forming in East San Jose’s working-class residential neighborhoods and around the plethora of markets and restaurants that popped up in strip malls.

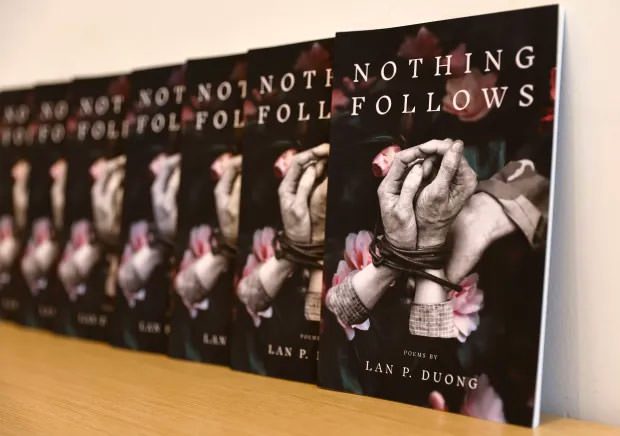

Duong, a USC associate professor in cinema and media studies, returned to her hometown Thursday to read from “Nothing Follows” (Texas Tech University Press,2023) at an event at the the Vietnamese American Service Center.

Duong’s stories certainly differ from popular cinematic narratives about Vietnam, which usually focus on the war and often sideline Vietnamese characters in favor of American male protagonists fighting an enemy in a hostile, foreign place. Duong’s novelist husband, Viet Thanh Nguyen, who also grew up in San Jose, once said he put Vietnamese characters front and center in “The Sympathizer,” his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, as “revenge on Francis Ford Coppola.” Duong similarly vowed to tell stories on her own terms after hearing her language butchered in Oliver Stone’s “Platoon.”

At her reading, which was co-hosted by the Vietnamese American Professional Women Association of Silicon Valley, she met up with family and friends from her old East San Jose neighborhood, including her older sister, Jacqui Duong, a Santa Clara Superior Court judge, who served as moderator. Duong, who has two children, 9 and 3, said she returns to San Jose every few months to visit her father, who is 93 and in failing health.

Duong, who arrived in San Jose in 1980 at age 6, expressed her pride and affection for San Jose. But she warned that her “dirty stories” reveal the “underside” of a refugee’s life in the city, including the “intergenerational trauma” that survivors of war pass on to their children and other issues that Asian immigrant families prefer to keep hidden in order “to save face.”

San Jose was formative for me,” Duong said. “But I’m also committed to telling my dirty stories of growing up here, where I experienced racism, sexual objectification and assault, but where I also have the joy of meeting with friends I have made after all these years.”

“These are our stories,” said Ann Nguyen, an attorney and board member of the organization that co-hosted the event. “We grew up being the outsider, the poverty, having to learn English.” San Jose State sociology professor Hien Do agreed: “These are critical stories to show our commonalities with other immigrant groups. That’s what makes San Jose such a great place.”

Duong’s poems emphasize a female perspective and Vietnamese survivors: a father and children who are trying to make a new life in a culture that sometimes feels hostile and foreign. Duong, whose family initially left Vietnam in 1975, also uses the language of poetry and memoir to uncover meaning in ordinary moments, often centered on recognizable San Jose locations.

She writes how she and her siblings carry “clothes, pans and secondhand sandals” into their rental home north of Tully Road; sleep three sisters to a bed; and ride in a car with her older brother on Story Road to buy beer, listening to REO Speedwagon on the eight-track and hearing him reveal he was molested when the family was living in a refugee camp in Guam. She also writes about a much-older brother who fought the Viet Cong in 1972. He nurses his sense of displacement in the United States by drinking too much and vowing to return to Vietnam to “kill the communists.”

Duong’s poems recount other trauma. She and girlfriends, as young as 9, became targets for sexual objectification and abuse by older men or boys — a common plight, she said, of immigrant girls.

Entering her teens at Yerba Buena High School she found herself straddling two identities. She was the “model immigrant” who attended church on Sundays and studied so she could go to college. But she also got into her share of trouble with her friends, latchkey kids like herself.

“We created our own fun, cutting class, getting into fights, going to night clubs with fake IDs,” Duong said in an interview. In a poem, she describes the allure of boys, identified as “Vietnamese gangsters,” who became the focus of concerns about youth “super predators” in the 1980s and 1990s. Duong writes that a 15-year-old boy called “Babyface” let her hold a gun he planned to use to rob a jewelry store. “He’s saying he likes me, that I look sweet,” Duong writes. Later, she hears on the news that he’s been arrested and sentenced to 15 years in prison for assault with a deadly weapon.

Duong’s father remains a powerful and complicated presence in her poems. He had to raise her and her siblings without their mother, who stayed behind in Vietnam for 20 years for reasons that never became clear to Duong. He grew up French colonial rule wanting to be an artist but was pushed into the seminary, then the military. Coming to America meant a crushing loss of status that could be humiliating, including when he collapsed in his car muttering after being scolded in a supermarket checkout line. But he always doted on Lan, his youngest child, and would announce at every family celebration: “I carried her in my arms when she was 2 years old, from Saigon to America.”

Duong told the audience Thursday that not wanting to hurt her father is the reason she took 25 years to write her poems. He’s part of that older generation who’d prefer she keep silent. But, she said, “I wanted to commemorate his life and breathe life into the complexities of his personality, and by extension that older generation and the difficult choices they had to make. I do bare it all: The good, the bad and the ugly.”

Martha Ross | Features writer

Martha Ross is a Bay Area News Group features writer for The Mercury News and East Bay Times who covers everything and anything related to popular culture, society, health, women’s issues and families. She has previously reported or edited for Bay Area news and lifestyle publications, including Walnut Creek Patch, and Diablo, Oakland and Alameda magazines, as well as The Nation in Bangkok, Thailand and The Economist. She graduated from Northwestern University with a BA degree in German studies and from Mills College with a MFA degree in creative writing and English.