By Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai

Hanoi has always been a city of tales and legends. Its ancient name, Thang Long, which means “the Rising Dragon,” comes from a tale about Emperor Ly Thai To witnessing a golden dragon ascending when he moved the capital here in 1010. The city is now the heartland of Vietnamese literature — home to many of our finest writers, literary festivals and book fairs.

Cradled by the silky Red River, Hanoi is also a city of loss and survival: It was destroyed time and time again during the French Indochina War, then the Vietnam War, when thousands of tons of bombs were dropped onto the city. But once in Hanoi, you will feel the energy of a city that constantly renews itself.

What should I read before I pack my bags?

Vietnam is too often seen through the prism of war, but it is a place with more than 4,000 years of history and culture. A fun book to dive into is “The Food of Vietnam,” by Luke Nguyen. The chapter about Hanoi serves you delicious introductions to the city’s most treasured dishes, such as cha ca (traditional fish cakes), bun cha (noodles with grilled meat and fried spring rolls), banh cuon (steamed rice crepes) and pho (Vietnamese noodle soup).

Hanoi is a city of poets, and one of my favorites is Ho Xuan Huong, whose daring and thought-provoking poems have been translated and published in “Spring Essence: The Poetry of Ho Xuan Huong.” For a contemporary poetry collection, check out “The Women Carry River Water,” by Nguyen Quang Thieu. If you prefer to get to know Hanoi via fiction, “Dumb Luck,” by Vu Trong Phung — a sarcastic novel set in Hanoi during the colonial period — is considered a classic of Vietnamese literature.

“Understanding Vietnam,” by Neil L. Jamieson, offers a deep examination of our country through poetry and fiction. “Hanoi: Biography of a City,” by William Stewart Logan, and “Hanoi of a Thousand Years,” by Carol Howland, both explore the life and history of this ancient city.

What books can show me other facets of the city?

The people of Hanoi have experienced countless wars, political turmoil and daily challenges to survival. Vietnamese writers, in documenting these experiences, have had to overcome a strong culture of censorship, practiced not just by the government but also by publishers and editors who need to protect themselves from harm by censoring not only whole books but paragraphs, sentences, words.

Most books about Hanoi haven’t been translated. Among the few that have, I highly recommend “The Sorrow of War,” by Bao Ninh, which tells the story of Kien, a Hanoi boy who went to war and returned a traumatized man. First published in 1991, the novel was banned in Vietnam until 2005 because it contradicted the official viewpoint that, since North Vietnam had won the war, there should be glory, not sorrow.

For the book to be published again in Vietnam, the author had to change the Vietnamese title from “The Sorrow of War” to “The Fate of Love.” Now the original name of the novel has been reinstated, and Bao Ninh is being hailed as one of the greatest Vietnamese writers. His most recent short story collection, “Hanoi at Midnight,” documents the complex lives of the people here.

“The General Retires and Other Stories,” by Nguyen Huy Thiep, daringly criticizes socialist ideas and brings to life the struggles and courage of Hanoian people. “Behind the Red Mist,” by Ho Anh Thai, is another thought-provoking and innovative book.

I highly recommend “Last Night I Dreamed of Peace,” the diary of Dang Thuy Tram, who was killed on the battlefield at the age of 27 while working as a doctor during the Vietnam War. Her diary was brought back to the United States by an American military intelligence officer, Frederic Whitehurst. Thirty-five years later, in 2005, the diary was returned to her family in Hanoi, then published to international acclaim.

Another female writer whose work I admire is Le Minh Khue, whose short story collection “The Stars, The Earth, The River” is mainly set in Hanoi’s working-class neighborhoods and depicts a grittier city.

What audiobook would make for good company while I walk around?

The Vietnamese poet Phung Quan once wrote, “During the moments of difficulties, I hold on to the verse of poetry and pull myself up.” Poetry is a pillar of Vietnamese life and, as you walk around Hanoi, you can listen to “Lanterns Hanging on the Wind,” a two-part, bilingual radio program celebrating Vietnamese poetry. The Vietnamese versions of the poems are read by the authors, and the English translations are read by Jennifer Fossenbell, an American poet.

While spending time Hanoi, you may find yourself on Hai Ba Trung Street, named after two warrior sisters who, according to legend, rode on the backs of elephants, leading an army of mostly women to defeat the Chinese colonizers around A.D. 40. The audiobook of Phong Nguyen’s “Bronze Drum,” narrated beautifully by Quyen Ngo, will transport you into the lives of the Trung sisters.

What literary landmarks and bookshops should I visit?

Hanoi’s 19/12 Street, dedicated to books and booksellers, is right next to the historic Hoa Lo Prison, nicknamed the “Hanoi Hilton” by U.S. prisoners of war. Local book companies and publishers have stores along the thoroughfare, displaying and selling their titles. As you walk under the green canopies of ancient trees, reflect on this fact: This street used to be a busy market — the Underworld Market — named for the mass graves of victims killed during the Anti-French Resistance War.

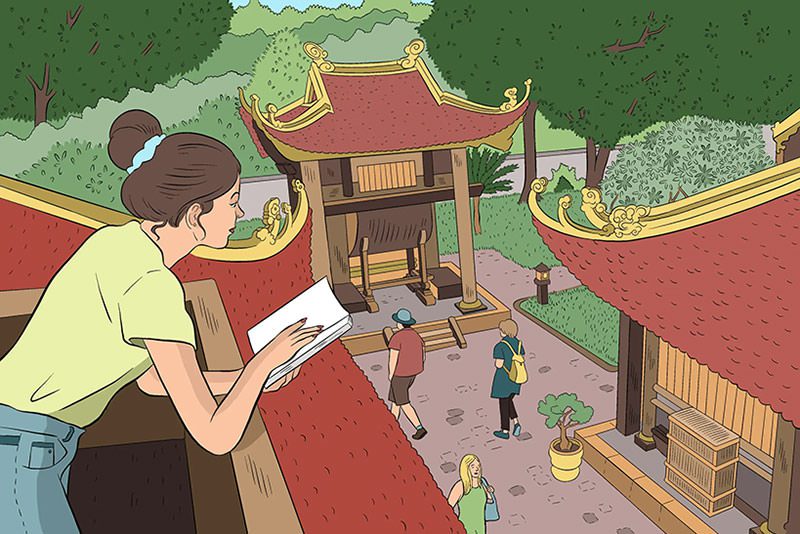

The Temple of Literature, where the annual Vietnamese Poetry Day celebration is held two weeks after the first day of the Vietnamese New Year, is a must-visit site. While you are there, stand in one of the ancient courtyards, close your eyes and imagine listening to Vietnamese poets reading to thousands of Hanoians who consider Poetry Day a highlight of their new year.

To the west of the city, the Vietnam Museum of Literature will enable you to get to know many of our foremost writers and poets. A book cafe has just been added to the building and is a good place to relax.

Trang Tien Bookstore and Thang Long Bookstore on Trang Tien Street, near the Lake of the Restored Sword, will give you a glimpse into books being published locally.

Nearby is Dinh Le Street, lined with indie bookstores, each with a small range of English books. Around the corner, on Nguyen Xi Street, many secondhand books are sold. On this street, you can also find banned books, which include those written by Hanoi writers who have had to publish their work overseas, only to see copies of those books smuggled back into Vietnam and sold here. A few years ago, I came to a bookshop here asking for the novels of Duong Thu Huong and was told by the seller that he didn’t carry them. But later, when I was paying, he asked in a whisper if I really wanted to buy the titles I had mentioned. I nodded and he took me up several flights of stairs, to the top floor, into a dimly lit back room where he handed me the books.

For a fun time, hop on the back of a motorbike taxi and let the driver take you to West Lake and Tran Quoc Pagoda. On the way, ask the driver to stop by Bookworm Hanoi — one of the largest foreign-language bookstores in the country — which has a good collection of well-preserved vintage books on Vietnam.

If I have no time for day trips, what books could take me farther afield instead?

“Beneath Saigon’s Cho Nau,” by Paul Christiansen, is an excellent essay collection that takes you to southern Vietnam and highlights many aspects of our culture and lifestyle, including rice wine making and whale worshiping. “The Defiant Muse: Vietnamese Feminist Poems from Antiquity to the Present” will transport you to many regions of Vietnam, as well as into the hearts and minds of our people, using the rich Vietnamese poetic traditions.

Note: The Vietnamese words in the original version of this essay used diacritical marks. To comply with New York Times style, the marks were removed before publication.

Unfortunately, this practice alters the meaning of the words. In the case of Hỏa Lò Prison, for example, “hỏa” means “fire,” and “lò” means “furnace”: the Burning Furnace Prison. Without the marks, “hoa” means “flowers,” and “lo” means “worry,” rendering the term “Hoa Lo” meaningless. I look forward to the day when The Times and other Western publications celebrate the richness and complexity of Vietnamese, and of all other languages, by showcasing them in their original formats.

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s Hanoi Reading List

- “The Food of Vietnam,” Luke Nguyen

- “Spring Essence: The Poetry of Ho Xuan Huong,” Ho Xuan Huong

- “The Women Carry River Water,” Nguyen Quang Thieu

- “Dumb Luck,” Vu Trong Phung

- “Understanding Vietnam,” Neil L. Jamieson

- “Hanoi: Biography of a City,” William Stewart Logan

- “Hanoi of a Thousand Years,” Carol Howland

- “The Sorrow of War” and “Hanoi at Midnight,” Bao Ninh

- “The General Retires and Other Stories,” Nguyen Huy Thiep

- “Behind the Red Mist,” Ho Anh Thai

- “Last Night I Dreamed of Peace,” Dang Thuy Tram

- “The Stars, The Earth, The River,” Le Minh Khue

- “Bronze Drum,” Phong Nguyen

- “Beneath Saigon’s Cho Nau,” Paul Christiansen

- “The Defiant Muse: Vietnamese Feminist Poems from Antiquity to the Present,” edited by Nguyen Thi Minh Ha, Nguyen Thi Thanh Binh and Lady Borton

Born and raised in Vietnam, Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai is a novelist, poet and translator. Her most recent books are “The Mountains Sing,” which won, among other awards, the 2021 PEN Oakland-Josephine Miles Literary Award, and “Dust Child,” published in 2023. Her writing has been translated into twenty languages.