She’s wearing a gold lamé minidress.

It hugs her curvy hips and barely goes past her panty line. She offers a seductive smile at the audience before the two backup dancers cradling her petite frame down the steps deposit her on stage. How she doesn’t flash the audience or stumble in her four-inch stilettos, I’ll never know. “Xấu xí!” my dad scoffs before hitting the fast-forward button. I’m dejected but stay silent, not wanting to trigger an argument over a 3-minute song. Plus, it’s 1991. Who wants to spend the time rewinding the last few frames of a bootleg Paris by Night VHS tape so I can analyze some dance moves?

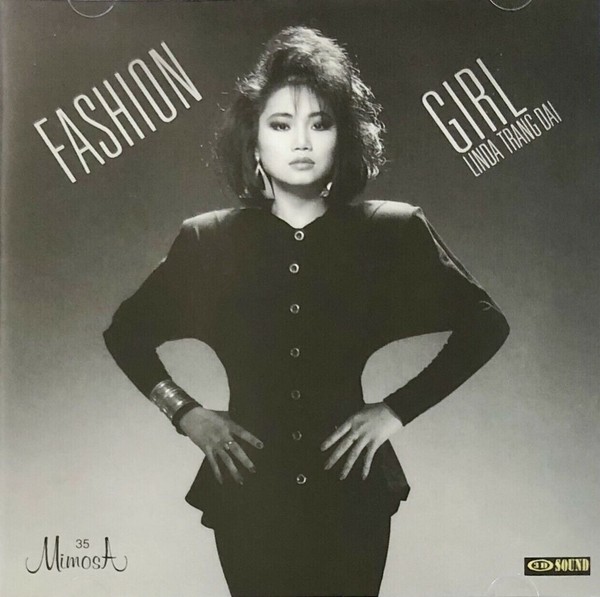

You may have sneered at her immodest wardrobe and raspy alto voice. But compared to other female Vietnamese singers on stage––demure mezzo-sopranos in áo dàis—Lynda Trang Đài was the only role model at the time who represented my dual identity: American but also người Việt. Her Madonna covers were my first exposure to American pop music. My four-year-old self yearned to shake my hips to the music and belt out a melodic verse while wearing what was practically lingerie on stage. As a mother now, I can’t blame my parents for discounting my aspiration. They didn’t survive the refugee camps for their kids to become sexpot musicians.

But it didn’t stop me from asking for formal training, with mediocre results. My mom deemed me “too chubby” for ballet class; playing the drums “wasn’t for girls.” I spent more time creating imaginary tea parties with P.B. (short for Piano Bear) during weekly lessons instead of practicing scales. What was the point when my already-overstretched parents were reluctant to drive me to competitions and recitals—sometimes forcing me to make up excuses for why I couldn’t attend? In their eyes, performances were best leveraged in front of their closest friends: a crowd accompanied by a bottle of cognac and a burning desire to pit us kids against one another to prove who’s the most talented.

In later years, my only musical solace was the surround sound stereo in my bedroom, the CDs alternating between acoustic-driven artists like Jason Mraz and then-popular Vietnamese singers like Trish Thuy Trang. The more preoccupied I became with heartbreak and homework, the less frequently I propped open the piano: a black ebony upright, covered in a lacy white sheet. My first year of college only confirmed the belief that performing music was “for fun” when my vinyl-collector-boyfriend decided he would not play for the marching band, despite spending most of his teenage years juggling lessons for three different instruments. It was like we collectively decided it was time to stop fucking around with hobbies that had no relation to our future careers. It was time to grow up.

Except for me, growing up meant graduating college a month before the subprime mortgage crisis hit, resulting in the Great Recession of 2008. It meant folding pastel-colored cardigans for a year while I waited for acceptance letters to roll in for a graduate program in public administration. It meant dodging black ice on the sidewalks of Denver, CO; where the Little Saigon comprises two blocks in the seediest part of the city in between Mexican taquerias and pawn shops. It meant swallowing the lump in my throat after each rejection I got—59 in total—before snagging my first job as an emergency manager for the fifth largest city in Washington state.

Except, the promise of 401k matches and health insurance didn’t make that ache to create go away. Sure, the 14-hour-days and 24/7 on-call phone didn’t help. But I knew something wasn’t right when I stepped off the bus one morning and crossed the street, my ankle boots clicking on the asphalt. Another bus turned into the tunnel, its gears groaning with exertion as my brain wondered what it would feel like if I “stumbled” onto the street into its path. Would the driver brake in time? Would the sheer force smash my body like a pancake or send me flying? Is getting hit by a bus a valid reason not to go into work? If I was thinking these things, did it mean I was suicidal?

When I finally worked up the courage to quit—nearly two years after that incident—I gave myself space to explore what I really wanted in life. For too long, I had defaulted to my parents’ definition of success: Get another 9-5 job (preferably one that paid more than my former government position so they could brag about my salary to their friends), buy a new car, acquire a collection of designer handbags and shoes. Instead, I lit sage sticks and scribbled in journals. Joined a woman’s moon circle, where we chanted mantras in Sanskrit and swayed to drum beats. At this point I rarely listened to Vietnamese music, preferring 90s R&B throwbacks and what Spotify categorizes as “indie pop.” So, imagine my surprise when I saw Lynda Trang Đài again during a guided meditation, dancing to the opening beats of “Material Girl” in her gold lamé minidress. Instead of clarity, all I had were more questions for my subconscious. Was I supposed to become a singer when I grew up? Or a public speaker? How did this tie-in with all the other incompatible Lego blocks of my career as a policy researcher, emergency manager, and freelance copywriter?

Like all things we obsess about, sometimes we stumble on the solution when we’re not thinking about it. My infant daughter was not interested in drinking milk from a source that wasn’t my breasts, so I purchased a Kindle to pass the time during nursing sessions. Devouring fiction became my norm, alternating between fluffy rom-coms like Helen Hoang’s The Kiss Quotient and literary masterpieces like Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s The Mountains Sing. But as thrilled as I was to see more Vietnamese stories coming to the forefront, I still didn’t see my experience represented: Growing up middle-class, falling in love with a white man, and realizing how miserable I was pursuing the American dream my parents risked their lives for me to have.

So, I started writing again—another hobby I had picked up during my senior year of high school and abandoned after graduating college. And to fuel my early morning work sessions, I filled the silence with music. When I discovered Dan Nguyen’s Vietnamese Nu-Wave mixes, it was like someone had taken me back to that memory of watching Lynda Trang Đài gyrate on stage, seamlessly swapping between English and Vietnamese verses, to my little four-year-old self… and thinking, “I want to be like that.”

And that’s when it hit me: I was taking the image too literally. The stage was really a platform; Lynda Trang Đài’s provocative choreography was a middle finger to the status quo of Vietnamese music about love, loss, and missing the homeland. She’s a creative visionary, a reminder that the best art evokes and provokes a reaction. American ballet dancer and author Twyla Tharp once described the act of creativity as “defiance”:

You’re challenging the status quo. You’re questioning accepted truths and principles. You’re asking three universal questions that mock conventional wisdom: Why do I have to obey the rules? Why can’t I be different? Why can’t I do it my way?

Of course, Lynda Trang Đài’s music is far from perfect. I may have snorted with laughter when listening to Supermarket Love Affair: a 90s techno-inspired song about locking eyes with a cute guy “in between the wine and detergent” of a grocery aisle. A cover of Miley Cyrus’s Wrecking Ball is an auto-tuned mess, with a clumsy stage performance that looks more like an 80s workout tape featuring ab crunches on gray exercise balls. A recent July 4th celebration introduces Lynda Trang Đài as the “legendary queen of Nu-Wave” as she struts out on stage in an American flag bikini top, paired with denim daisy dukes and a shredded vest that comes down to her midriff. Her back is turned to the audience, pounding drumsticks on the cymbals while a foursome of other has-been Vietnamese pop stars jump around and sing off-key verses, making the performance feel more like a drunken karaoke party with friends than a reunion concert.

Except this time, I’m thirty-five years old. Palm trees sway outside the windows of my friend’s ranch-style home on Oahu while the air conditioner hums in the background. My daughter’s in bed for her afternoon nap, meaning I have time to type out a few work-related chat messages before scanning through editor notes on the first eight chapters of my manuscript, jotting down a list of which revisions to tackle first. In some ways, writing a story about growing up Vietnamese-American feels like stripping down to a skimpy outfit on stage, with the fear that no one will understand the message you’re trying to get across. What if I work on this novel for years, only to have no agent pick it up? What if the publishers aren’t interested in diverse books by the time I finish? What if someone reads it and leaves me a one-star review on Amazon?

But then I load up a Lynda Trang Đài performance from the early 90s. She’s dressed in a white pantsuit, her hand cocked on her hip before she strips down to a metallic bralette, shorts, and knee-high boots. Two guys in black jumpsuits twirl beside her before flexing their biceps, looking like they belong on the stage at a Chippendale’s performance instead of a music variety show. A helicopter serves as a prop in the background as she arches her back, looks up to the sky, and yells the final lyric: “Express yourself!” Even 31 years later, I feel chills running down my spine when I hear that late 80s synthesizer sound so characteristic of Vietnamese pop music arrangements. It’s also when I realize she doesn’t give a shit what anyone thinks of her revealing outfits or reverberated vocal quality. That confidence is showing the world what you’re capable of, no matter what people say or think.

So I write a little more, despite my husband’s reminder that “we’re on vacation.” When I finally head into the bedroom to wake my daughter up for dinner, I’ll do what I always do: stare at her profile, in awe of her wavy copper-tinted hair and milky white complexion. She’s exactly what I hoped for in a little girl: Independent and opinionated, with a broad range of musical tastes ranging from Nina Simone to Vivaldi. She also has a talent for drawing and painting that neither my husband nor I possess. The walls of our kitchen, living room, and offices serve as her art galleries: circular blobs with lines in crayon that she enthusiastically describes as “spider webs”, lopsided hearts shaded with oil pastels, wooden models in an unappealing shade of poop brown because she insists on mixing all the tempera paint colors together. As someone who hates smudging ink on their hands, the biggest challenge of motherhood is allowing my daughter to make messes in the name of creativity.

But then I hear her joyous giggle and forget about the paint smears on my white jeans. Remind myself that I’m not my parents, traumatized by a decades-long fight for their country’s independence. They had no choice but to cross the ocean to give their children a chance at American citizenship. But it came at the cost of losing the tenets of Confucianism, where the group collective trumps individual expression. It’s something I’m still struggling to accept, knowing it may take years to become a full-time writer. Tomorrow morning I’ll probably wake up in a cold panicky sweat, wondering if I’m wasting my time when I could spin my Aeron chair in a cubicle, plotting my next promotion.

But then I’ll remember that my daughter’s counting on me to show her how to balance one’s creative whims with the entrepreneurial skills needed to sustain a lifestyle. And that’s what gets me to roll out of bed and tug on my yoga gear—a low-cut crop top and figure-hugging leggings that would make Lynda Trang Đài proud—ready to take on the day.

Sophia Le is a Vietnamese-American writer based out of Seattle, WA. When she’s not crafting chapters for her debut novel Eight Years Later, you can find her exploring local bookstores with her toddler, managing projects for her software clients, or reading on her Kindle while sipping a tea latte. For the latest book updates, join her newsletter or follow her on Instagram.