(Editor’s Note: This essay explores, in part, the work of Viet Thanh Nguyen, who is the Publisher and Founding Editor of diaCRITICS.)

By playing with questions of authorship and ownership, Monique Truong’s luminous debut novel The Book of Salt operates, Y-Dang Troeung has suggested, “as a creative/theoretical intervention in the debate about postcolonial collaborative autobiography.” Troeung’s astute phrase—a creative/theoretical intervention—may just as aptly describe her own book Landbridge: Life in Fragments, and Viet Thanh Nguyen’s A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial, which were both recently released in 2023. In both texts, the authors experiment with formally innovative narrative structure to push boundaries around the how and what—the technique and content—of Southeast Asian American life writing.

Troeung, born in 1980 in the Khao-I-Dang camp in Thailand, grew up in Goderich, Ontario, which she fondly describes by its literary name of “Alice Munro Country.” At the time of her death from pancreatic cancer in late 2022, she was an associate professor of English at the University of British Columbia. The posthumously published Landbridge compiles letters, archives, family photographs, and prose sequences that render testamentary, with startling lucidity, her and her family’s experiences in Cambodia and Canada. Nguyen’s A Man of Two Faces, meanwhile, is a part-bildung, part-ars poetica, all-polemic text that collects arguments from his earlier public speeches and essays to reframe his coming of age as an Asian American writer. It continues his longstanding creative and critical interest in the cultural memory of the U.S. war in Vietnam; rather than simply retreading old ground, though, his latest book is centred on the internal ruptures that emerge from his upbringing in San Jose, California. In particular, it is haunted by his desire to pay tribute to his parents—especially his late mother, Nguyễn Thị Bãy or Linda Kim Nguyen—and to explore the question of “where, on the thin border between / history and memory, can I re / member myself.”

As Troeung’s reading of The Book of Salt points out, Southeast Asian American life narratives by refugees are shadowed by the genre’s fraught origin in “collaborative autobiographies” that Troeung notes were “marked by a history of exploitation and unequal power dynamics.” Landbridge and A Man of Two Faces, however, refuse a model that exploits the vulnerability of authorial self-disclosure. Troeung and Nguyen similarly recuperate collaboration by situating their writing in heritage and community, while delivering memorials and testimonials on their own terms.

Landbridge incorporates and expands on material previously published in Troeung’s first book, Refugee Lifeworlds. In a preface without page numbering—speaking, that is, from a world that governs beyond the space of the text—Troeung tells her reader, “In this book, theory, fiction, and autobiography blur through allusive fragments. These fragments—a perforated language of cracks and breaks—seek to knit together, however imperfectly, the lifeworlds that inspire me to write here, on this page.” Continuing her project from Refugee Lifeworlds, Troeung further recovers—salvaged from an external, imperialist “logic of minor anecdoting,” where Cambodia serves as “a ‘minor detail’ in the narration of something else”—the “fragments, anecdotes, sketches, vignettes” of her family stories.

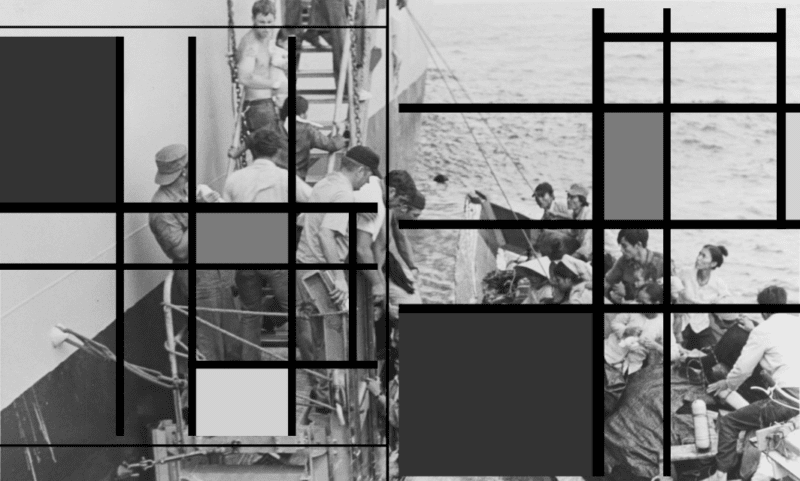

Much of the writing in Landbridge is in the present tense, even in the historical sequences set during Troeung’s parents’ youth in pre-war Cambodia. One section, “[remembrance],” sketches Troeung’s life through family incidents that have taken place on Remembrance Day over the years. The snippets, which include memories of her own childhood and a brother’s arrest, appear at first to be organised chronologically, but they reveal a non-linear narrative in how the section is bookended by her son Kai’s life-threatening seizure in November 2018. Other textual circuits include the reproduction of a clipping from a 1980 issue of the Montreal Gazette, which featured an eleven-month-old Troeung and her mother Yok in the snow. The front page is first reprinted in Landbridge without context; the incident is not addressed until a section more than forty pages later, which extracts the photograph from the page. Encapsulating one emotional strain in the text, Troeung writes in “[remembrance]” that “I feel as if it’s all added up to here, all the years, all the deaths, the illnesses, the losses. They all add up and up and up”—a cumulative mode that recalls Ma Vang’s description of Hmong subjects “dragging history” from ephemeral pasts into a precarious present.

As with the continuity between Troeung’s first and second books, Nguyen’s memoir also features narrative techniques that he previously tested in his fiction. Much of A Man of Two Faces evokes typesetting idiosyncrasies from Nguyen’s novels, such as the use of centre alignment and right justification, the conceit of sardonically representing the name of the United States in print as “AMERICA™,” and even the use of black-out text and parentheses, censor-style, to euphemise the name “Trump” and the racial identifier “white.” Most notable, though, is Nguyen’s experimentation with first- and second-person narration, which he premiered in his Pulitzer-winning The Sympathizer and its sequel The Committed. The narrator of Nguyen’s novels refers to himself with the pronouns “I,” “you,” and “we” at different points in the narrative. At the conclusion of The Sympathizer, the narrator splits into “me and myself,” becoming an inconsistent “we.” In The Committed—which is broken into sections sequentially titled “We,” “Me,” “Myself,” “I,” “Vous,” and “Tu”—the narrator, occasionally using the author’s own baptismal name of Joseph Nguyen as an alias, splinters further.

A splintered self, originating in an improperly remembered past, recurs in Nguyen’s memoir. Nguyen has alluded on occasion to the formative experience of enrolling as an undergraduate in a workshop with the celebrated Maxine Hong Kingston, and dozing off in every session. A Man of Two Faces sheds more light on the episode by including an extract from a letter by Kingston that states “you seem alienated and depressed,” and surmises that the adolescent Nguyen is showing symptoms “of withdrawing and not functioning.” When Nguyen retells the story in a speech in Singapore, however, he summarises the encounter as one where “she advised me to go seek psychiatric help.” After a beat, he continues, “I never did. Instead, I became a writer.” This recount is punctuated with uproarious audience laughter—which turns a moment of crisis in print into a punchline in person, and deepens the alienation that is expressed through the author’s widespread reference to himself as “you.”

A Man of Two Faces switches to the second person early on, and does not resume the use of the first person until the end of the second of the book’s three parts. The shift occurs fewer than a dozen pages in, during a dialogue when the nine-year-old Viet is informed that his parents have been shot in a robbery. “What’s the matter with you?” his older brother asks, troubled. That question haunts Nguyen throughout the narrative, in the wake of his inability to remember either the aftermath of his parents’ shooting or the circumstances of his late mother’s mental breakdown. The emotional impact of her illness is first suggested when “[o]ne day, Má disappears.… Your mother comes back, but you do not remember her return.” Yet this illness is not mentioned again until the mid-point of the book, when an adult Nguyen, despite his brother’s reminders, “cannot or will not remember” her diagnosis or prescriptions. The psychic fragmentation of Nguyen’s self is closely linked to his mother’s illness, since the first person reappears during an interlude of good health in 2003, when “[n]either of you know that in two years / nothing will be the same, ever again, / for her. Or you. Or me.” Where a more conventional autobiography might seek to recover lost knowledge and fill the gaps, Nguyen’s text instead embraces an epistemic failing. “I reject my memory. I accept my amnesia,” he writes, adding: “Forgetting the painful things is necessary for some of us.” The promise of a faithful recount, from memory—the premise of a memoir—is thus subverted.

But evident from both books’ subtitles is the fact that neither A Man of Two Faces nor Landbridge set out to present themselves explicitly as memoirs. In fact, Christopher B. Patterson, in an interview with Julia H. Lee, suggests his partner Troeung was inspired, in writing Landbridge, by the narrative structure of The Sympathizer.

“It’s framed as an ethnic memoir, as an autobiography,” Patterson says of Nguyen’s novel, when in fact “it’s a confession being made under duress and torture.”

In the same vein, “part of the point for Y-Dang—you know, she was thinking about this when writing Landbridge—was to understand how life story is often told under duress, and has a lot to do with life and safety, especially for refugees.”

Through the framing of a forced confession, then, Landbridge immediately turns on its head the identity of the implied reader, or the imaginary person who “is constructed by the critic who predicates a particular reader response on the work,” as narratologist Monika Fludernik has explained. “[S]o often the speech of refugees is met only with the silence of an unreceptive public,” Troeung writes. In Refugee Lifeworlds, Troeung has already theorised refugee aphasia as a phenomenon related to “the constant demand to retell these stories [of trauma], to relive these events, and to do so in ways that are recognized and encouraged by the host nation.” This experience of speechlessness—companion to Nguyen’s enforced amnesia in A Man of Two Faces—recalls the titles of two poems from Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky as Exit Wounds: “Anaphora as Coping Mechanism,” and “Logophobia.” In this framework, language is both an instrument of violence and, through the traumatic and/or creative repetition of anaphora, also a possible means of recuperation and recovery.

Yet Troeung explains near Landbridge’s conclusion that “I wrote this book because I do not want us to see this history [of war and genocide], Year Zero, as our origin story… I return to Pol Pot time because I do not want to be stranded there, at the edge of those mass graves.” Interleaved between the titular fragments in Landbridge are epistles from Troeung to her son, which recollect his birth and infancy, and express her hopes for his unseen future. Her words, which take on increasingly bold resonance in the context of her impending death, make clear that her writing is rooted in healing for her self, family, and community, and is not an appeal to a reader who must be convinced of her dignity. Similarly, A Man of Two Faces, set up as a monologue directed at “the writerly you,” sees Nguyen tell himself that “[t]he only way I have been able to write about myself is through writing about you. You are me, but seen from a slight distance, or the greatest distance, which is the space between one and one’s self.” While it wavers in places, the text is a belated attempt at redressing Kingston’s call for him to “be open, engaged, speaking, hearing, awake,” and the injunction from another of Nguyen’s teachers, the author Bharati Mukherjee, to write in a way that cuts to the bone.

In this way, Troeung and Nguyen’s writing—which is by turns frustrated, assertive, and compassionate, but always clear-eyed—rejects an oppressive narrative model that expects refugee subjects to humanise and justify themselves. These memoirs, because of their inward orientation, afford both authors room to hold space for what might otherwise go unacknowledged. At one point in Landbridge, Troeung recalls how her parents had to suppress intimacies of kinship and language, when, in the presence of unseen Khmer Rouge informants, “[t]hey reminisce about a past they have never lived, fabricating memories that conceal their family ties. They do not call each other by their real names; they do not speak their native Chinese language.” This aspect of the text stands as tribute to cultural resilience and her family’s Chinese heritage. Nguyen, meanwhile, extends his reflections on the false binary between victim and perpetrator—which he has explored in earlier works, such as the article “Refugee Memories and Asian American Critique” and the essay collection Nothing Ever Dies—by revisiting his parents’ resettlement, as Catholic refugees from the north, on the lands of indigenous highlanders in his birthplace of Ban Mê Thuột. “Sometimes binaries are inadequate,” he writes. “In Việt Nam, you were colonized but also colonizer”—the same contradiction, he implies, that applies to refugees’ presence as American settler colonists. So, even as they retain the genre’s testimonial responsibility to bear witness, Troeung and Nguyen, by asserting the ethical position and the aesthetic and critical value of the communal and the deeply personal, repurpose the objective of Southeast Asian American memoir.

H.M.A. Leow is a Singaporean writer and a PhD student in English literature, working on a doctoral project about transnationalism and race in 21st-century Southeast Asian American literature. She is interested in narratives about empire and nation, as told through memory, migration, and food.

H.M.A. Leow is a Singaporean writer and a PhD student in English literature, working on a doctoral project about transnationalism and race in 21st-century Southeast Asian American literature. She is interested in narratives about empire and nation, as told through memory, migration, and food.