When she became ten, her mother took her to the shore with the net. They wore shoes over the low and rugged rocks, and the mother asked her to bend her knees, squat slowly so they do not crack.

“You are close to the ground, just like them,” she says, tongue in cheek.

She listens to mother, squatting, knees above ankles, ankles above feet, feet on the rocks. My body like theirs, a mirror over the water, gentle gaze towards the sand and whoever is inside. Unrolling the net, mother spreads it in terms of her wingspan. The net touches the surface, then the water lets it in, as liquids do. Without the air, the net falls towards the sand and settles into the grains.

“I see one over there,” she tells her mother, “clinging to the side of the rock on the left.”

Mother does not look up, still looks down, at the net on the floor. “It will come,” she says. “They’re not expecting us to be here. There is no bait.”

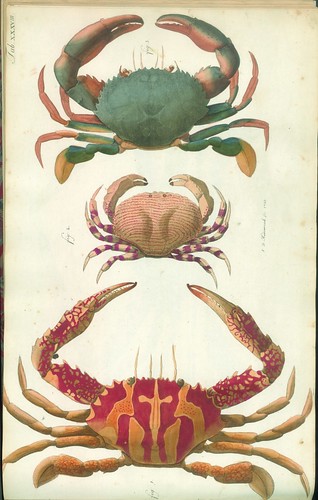

And surely it comes, crawling sideways, lingering atop the net, and mother’s gaze remains the same as a few moments ago, clasping the net shut, pulling water upwards, dripping, no longer airless, but rising violently to their ears. The crab thrashes, but this is no floor, only net, only mother’s hand holding it in suspension. She laughs and goes, “Look at him! Little bug of the sea!”

The daughter shifts her weight on her heels, rises up and looks at his bead black eyes.

I will take you home, bug. I will put a pot of water on the stove. I think you will feel fear and suffering, but your body will not be broken until after you die. According to our people, that makes you special. Instead of a dagger to the throat or a swift decapitation, your body retains your image to the person who tastes you first. You are meat, but more than that. Are you more than that?

Your shell will turn orange and insides will turn white. You will sit on a bed of herbs, glazed with oily garlic, from a garden you have never touched. Your shit will be buttery and sucked into the mouth, lips kissing your shell—tight. And on some occasions, you will be dressed in red curry: sweet, thick from a coconut, with a sprig of coriander sitting on the surface as garnish, not yet sinking, like the net at the surface of the water you were born. A body and decor.

We love you, little bug, and I am not sure we respect you. Your ontology will always be different from ours. Though we claim to be gentle when we clamp down our teeth, we expect you to return your flesh in docility and faith. Little bug, for you it does (not) matter if tomorrow will come.

A few decades pass. The girl and her mother are now in the water, too. They had lived their entire life by the shore, sometimes swimming, sometimes diving, but most of the time squatting, like I told you. Then, jolting up, tall, net in hand, bug thrashing.

***

There were people in the village that live on a slope, other women and girls, too. The girl and her mother had once envied them quietly. The slope women’s skin was blotchy and pale. Their women carry small dropper bottles of a liquid that stripped the oils from their skin. You could always tell she lived on the slope if she carried a pouch with square-shaped cotton pads and that dropper bottle. At home, atop their nightstands or boudoirs, they owned various other dropper bottles of oils, which were carefully blotted onto their cheekbones every morning and evening (to return the oil to their round, taut faces, of course).

“Do you ever wonder,” a girl said once, blotting the apples of her face gingerly, “why I am so beautiful?” She gazed into her own eyes, squinting briefly.

“Every day, I am so beautiful,” she whispered, dipping a fresh piece of cotton into a glass jar. “These marks on my face,” the girl patted her gritty sores and filled her pores with the viscous liquids, “are part of me.”

Her mother stood behind her, a looming tree.

“They are always part of you,” she advised. “They are always part of us.”

And though both the women from the slopes and the women from the shore had shiny oily skin, the people insistently claimed they could always tell the difference between the women, it is always so easy to tell.

Slope folk had a view of the shore folk from above. This is normal now, too, even as all the mothers die and birth new mothers. If you travel around, even inland towards the marshes, the same general principle rings true. I assume I do not need to explore this much more.

A more curious change happened in the village as the years waged on, as the girl and her mother migrated from the shore to the water and sunk into the sand, into the grains. Traditionally, the shore folk’s diets consisted of bugs and fish from the water. Traditionally, the slope folk were disgusted with the practice. Long anguishing hours by the shore, in a squatted seat, in a quiet pose, waiting for a bug to crawl your way. It was disrespectful, the slope folk told their daughters, and there was no sport in waiting. Over time, however, the slope folk’s daughters wondered what the bugs tasted like. It must be so sweet, they thought, if the women labored so loyally for such a disrespectful craft. Further, some families living on the slopes had not tasted a creature from the sea for generations. The only tales they heard of the flavor had been foreign, whispered into the ears of girls who giggled with other girls. The same kind of bug that our mother snatched up with her daughter squatting nearby became of great interest to those on the slope.

Desire became too heavy to suppress. After some gossip and resignation, some of the women of the slopes decided to traverse their ways down to the shore, where the shore women slept and kissed and fought. And soon enough, they were in the water, where our mother and daughter now lay.

They squatted, slowly as to not to crack their knees, and wait for bugs, for a sideways walking crab to wander into their submerged nets. At first, the slope people were incredibly clumsy and ill-mannered–– they were too impatient to wait for a bug to crawl by, instead punching their hands into the water and complaining of their knees wobbling too violently.

“I don’t know how this happens,” one slope woman sighed. “I don’t know why I want this. No, I know that I want this.”

Some feet away, a shore girl watched this woman. At her perch, a safe distance for speculating, she wonders how someone could feel that way.

“Hey, you!” the girl called, voice shaking. “Can you tell me why you’re doing this?”

The slope woman looked up, to her left. She stared at the girl, sweat dripping down her temple. She did not say a word.

A few hours later, this woman caught her first bug.

***

The flooding of slope women to the shore confused some shore women. Other shore women hushed their comrades, assuring them that it was natural for the slope women’s fine and established intelligence to lead them to ponder their water and the creatures inside. While the slope women blundered around in the water, searching for crabs, the shore women wondered, watching, huddled under their roof coverings, will they ever be like us?

As the slope women spent more time in the once ignominious labor, their calves began to swell and harden. They relished in giddy pleasure when they caught their first bugs, shouting and boasting while their carefully lured fruit writhed in despair. Although their faces were still oily, their skin darkened, blotches healing from being exposed to light for so long.

Some of the shore women grew tired of observing, especially passively watching a slope woman twist her net in the wrong direction or shriek in fear when the bugs fought back. With practice in addition to guidance from the shore people, the slope women learned more and more each day. So now the shored and the sloped shared their nutrients, their hobby, their livelihood, and it did feel good to some. Very good!

But there are still some creaky and tepid shore women, sitting at the water’s edge with their legs spread in front of them, refusing to trust the slope women’s ways. These women swear they can tell that the bugs are not dressed remotely similarly to the ways in which they were in their youth. As they prune the garnishes carefully, they tell the shore girls of their worries.

We can teach them everything we know, they say, but it will never be right. It will never honor the life of the bug.

They say other things, too. They say that the slope women crush their shells with their teeth with such brute force that the sliver of love that the bugs so deserved was not a factor in consumption, that the bugs were dressed in the same herbs but were still somehow unrecognizable to the elders. There are other wrinkly, brown shore women who disagree with these claims, saying that there is no way to tell the difference any more. And there are other girls and women, quietly listening, but not sure what to say. It was not worth the distinction.

During one of these huddled conversations, a particular woman lost her temper.

“It was never honorable! The bug has always suffered! They were never, ever, different from us,” she shrieked. The woman stood up sharply, dropping her herbs.

As the delicate leaves and membranes fell to the ground and the huddled women looked up in punctuated shock, one bug escaped from a woven bag. In this moment, still in time, the bug sidestepped away from the huddle, away from the encampment, and down towards the water. No one noticed.

***

There was no resolution.

Days and months passed. The same shore women continued to debate amongst themselves, with those certain elders never forgetting to take the opportunity to warn young girls of the slope women’s disrespectful and even deceitful ways. Regardless, these shore women sat tucked away from the nets, the nets that will continue to jolt upwards to the sky.

Contributor’s Bio

Teline Trần received a B.A. in Comparative Literature from Reed College. They are thinking about writing homeland and faith via different mediums such as fiction, poetry, film, and the Internet. Teline lives along the Hudson River and is a fellow at Wendy’s Subway, a publisher and reading room, in Brooklyn, NY.