My father’s typewriter was both an object of transit and an object of passage, and looked like a real suitcase. One could easily imagine that he had arrived from his native Tonkin carrying his typewriter case elegantly as his only baggage.

A tool of transition, which could type his mother tongue as well as his language of adoption, the typewriter was at the same time a tool of correspondence between the world he had left, perhaps, and that to which he now belonged – France – but also between man and the cosmos.

My father was a diviner.

The carriage return still rings in my ears, as it regularly did after several dozen clicks of the keys. My father used to type administrative correspondence, horoscopes and letters for his family. He used to keep a trace of all his correspondence, duplicating it with the famous carbon paper. This thin inky sheet was itself such a mystery to us children. We would steal some of the midnight blue layers from the cardboard box in secret in order to scribble on it with our colored pencils, leaving traces of blue ink on the linoleum floor.

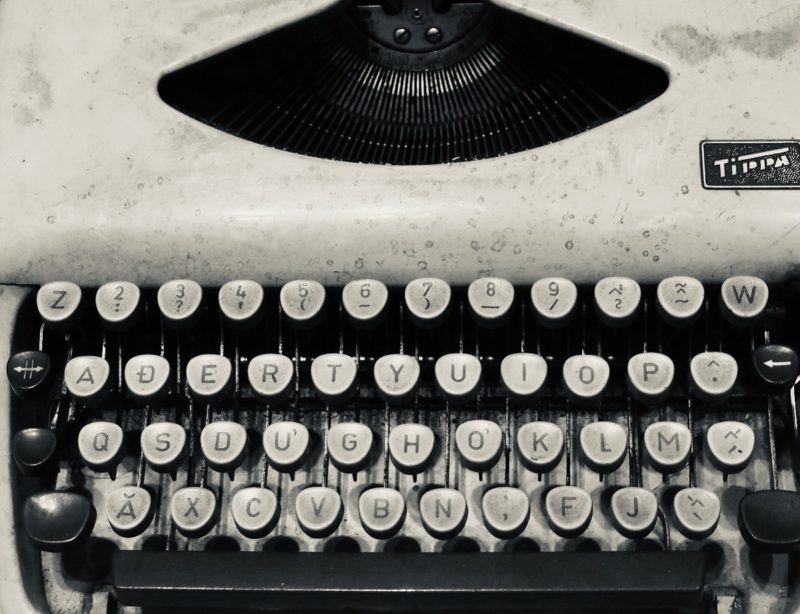

My father’s tiny typewriter was special. An exotic object that betrayed his origins in spite of himself, he who spoke French with no trace of an accent. You only had to look at the white keys with their special seemingly unpronounceable characters to imagine this man coming from elsewhere and speaking an unknown tongue. I attentively observed the letters decorated with incongruous signs whose tonality I struggled to imagine. Consonants topped with tildes, vowels donned with hats and locks of hair-like comas. Severe eyebrow Ă, bearded Ợ, or graced with a beauty spot under the chin, or Ủ coiffed with a cedilla. All because the tiny Olympia Splendid 33 had Vietnamese keys. My father was born elsewhere, but at home he everyday spoke a language that was not his native one. It took me years to realize this, so natural was it to hear him speak French. He didn’t try to pass on the Vietnamese language to us, or very little. It was a language that he associated with bygone times, with a lost world. He left in 1950, before the victory of the Vietminh at the end of the Indochina War, so he didn’t experience the transition between old Indochina and the new democratic Republic. He appeared to have detached himself from this native land.

But here was the machine.

*

It was a very compact object, miniature even, but ever so cumbersome! I didn’t know where to begin with it, even if my father did let me play with the carriage and showed me how to correctly insert a sheet of paper, turning the knob to wind it into place. This object looked like a toy. How could I take such a rinky-dink work instrument, such a hybrid object seriously? If my father had practiced calligraphy using a paintbrush and India ink, perhaps I might have found it less humiliating. He would have seemed even more exotic, certainly, but less ‘subjected‘. Indeed, that was what I reproached him for, long before reading what Frantz Fanon wrote about acculturation. For ‘quốc ngữ‘ – the name given to Vietnamese’s Latinized written form – is nothing other than a Latin alphabet with diacritics. Established in the 16th century by the Portuguese missionaries, it is the result of their evangelization mission. When I began to learn Chinese, both written and spoken, the Olympia Splendid 33 typewriter appeared to me to be a symbol of the acculturation of the Vietnamese people. Its authenticity was a sham. It existed because the original Vietnamese writing had bowed to the civilizing mission. Learning Chinese was, for me, a way to truly return to my roots, to the origins of this ideographic culture.

For my father, the AĐERTY keyboard was the link to his native land. Especially since he didn’t speak the language with my mother, who only spoke French, or us, his daughters, educated in the principle of “assimilation”. Deep in a closet, he accumulated letters written to people he’d left decades ago. Whole bags full of a correspondence in a foreign language. Blue envelopes, from the 1950s to the 2000s, By Air Mail, thin and light, whose stamps we systematically cut out. Inside all these lightweight envelopes, there were even thinner sheets, delicately folded, written in the hand of grandfather or uncles and an aunt. And with them, the typewritten sheets of my father responding. The AĐERTY keyboard thus expressed words destined for the family in internal exile, from North to South Vietnam, and then for the same people, now migrants in the United States. The words of one exile to other exiles. This keyboard set words in circulation, distanced words, necessarily, and often totally out of touch with reality. This often led to dialogues of the deaf, sometimes due to delays in forwarding the missives – fresh news having already become obsolete – but, most of the time, this misunderstanding came from the divide between what one person was living, and the other’s fantasy of it. My father’s siblings thus imagined us living in the opulent France of the post-war boom, because my father was too proud to tell them of our modest living conditions, the five of us squeezed into our thirty square meters. As for my father, as the oldest brother, he did his utmost to give advice to his younger brothers, outdated advice from Hanoi capital of North Indochina before Independence, nothing like Saigon, the Americanized south, or even less the Ho Chi Minh City of the ‘reunited’ country.

*

A quirky object, the tiny Olympia could readily be described today as a glocal one: it offers a ‘universal’ means of communication with a touch of ‘local folklore’. It would be very successful in an artist’s installation. Unfortunately, I had to get rid of it. It carried too much frustration, and then, above all, when my father passed away, it became mute. Before, without me really realizing it, the singing of the AĐERTY keyboard was already gradually more sporadic. The rhythm of the correspondence in Vietnamese waned due to the censorship of the post. My father kept on typewriting, not to be read, but to typewrite horoscopes on sheets that he first folded into twelve cells. My father practiced divination. Not as a hobby, but as a real job, he had cultivated a childhood gift, and then learned with the monks in the small streets of 1930s Hanoi. The Olympia typewriter wrote series of terms in each cell of the sheet. ‘Hợi’ for boar, ‘Tuất’ for dog, ‘Ngọ’ for horse, ‘Tỵ’ for snake, ‘Mão’ for cat, ‘Sửu’ for buffalo, and so on. Each cell corresponded to a ‘palace’ in the sky chart that my father drew on a recycled sheet of paper using a ruler and a Bic pen. Then he put it in the typewriter to fill the cells with the symbols that destiny gave the person who came to consult him to discover the past, present and future. For a long time, I considered it an archaic belief because I had no rational explanation. I finally understood. It took me half century to understand how, in this anachronistic and depreciated job, my father was waging his fight against Modernity. It was his way of keeping up his political combat. Persisting as a diviner in a world dominated by Science was his act of resistance. A language he was the only one to decrypt. A language to communicate, not with others, but with the cosmos. To establish this correspondence, the medium was this tiny typewriter with its special keyboard. An AĐERTY keyboard.

The piece was originally titled “Clavier A Đ E R T Y, un objet de correspondance” and published in French in L’objet de la migration, le sujet en exil, Presses universitaires de Nanterre, collection Chemins croisés, 2020.

Contributor’s Bio

Myriam Dao is an independent artist-researcher. An architect by training, she has a Master’s in Social Sciences (EHESS/ENSAPLV). Initially, she took her inspiration from research on vernacular architecture and landscape, and its confrontation with Modernity. These spatial issues gradually shifted toward sociological ones, focusing in particular on the indigenous ontologies. Her works embody knowledges and lived experiences that have been silenced, with small narratives, using writing, images, and performance. Forthcoming publications in collective chapters: “Hani Dwellings” and “Bamboo” in Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, Bloomsbury, and “Divinatory Arts and Tử Vi” in Liam Kelley, Phan Le Ha and Jamie Gillen Vietnam at the Vanguard: New Perspectives Across Time, Space, and Community, Springer “Asia in Transition” book series. She lives and works in Paris, France, where she was born.