“All immigrants and refugees, whether for a short moment or for the rest of our lives, will be obsessed and possessed by their past. It defines and perhaps nurtures us, giving us our identity, even when we struggle to develop a new self in a new home, a new land…” – Nguyễn Quí Đức

On the day of his passing, DVAN co-founder Viet Thanh Nguyen wrote on social media:

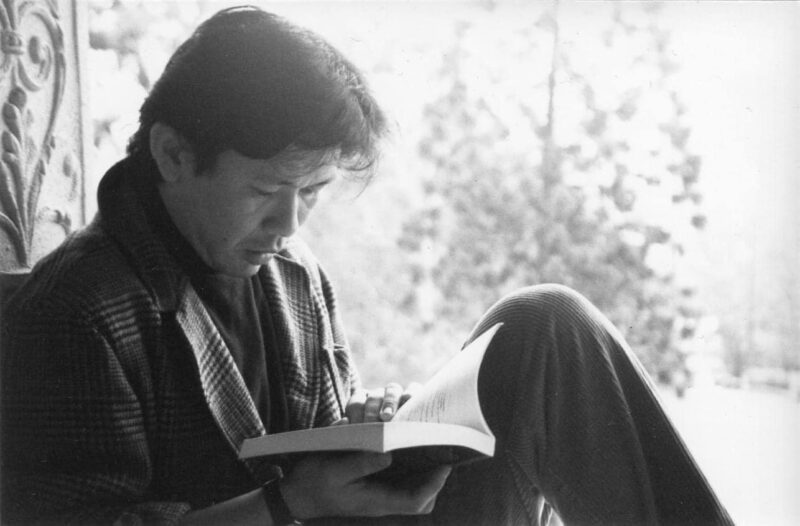

“This is how I remember Nguyễn Quí Đức. When I met him, I was in my early twenties and he was about this age in the picture [above]. I thought he was an old man. He was actually in his mid-thirties…. He was an NPR journalist when I met him and he gave me my first media opportunity, recording small pieces on the radio for his Pacific Rim show. He and I and several others started Ink & Blood, one of the first Vietnamese American arts organizations (it eventually became the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network). He wrote one of the first Vietnamese American books in English, Where the Ashes Are, a memoir. His father was the governor of Huế, and he became a world traveler and bon vivant. He eventually returned to Việt Nam and opened Tadioto, a bar in Hà Nội that was a meeting place for artists, exiles, diplomats, and cultural workers of all types to congregate. He bought a place in the mountains of Tam Đảo and turned it into an architectural showcase. He invited me to stay there by myself for a few days. He was generous with that house and everything he had, including his time. I think of his life as his most important work of art. That work is now finished. No one who knew him will ever forget him.”

Very few know that it is indeed Nguyễn Quí Đức who inspired Viet and I to co-found DVAN some 15 years ago.

Last September, we expected him to be at our Writers Residency in the South of France. He canceled the month before when he learned that he had an advanced stage of lung cancer. Along with so many others, we all mourn Đức.

Đức was our mentor, our friend, the person who always showed up and welcomed us. Last spring, when he visited San Francisco, he put forth the idea of creating a DVAN chapter in Vietnam, with Tadioto, his bar in Hanoi, as headquarter.

On a social media post, Monique Truong cited a quote from his essay “Memory”:

“The language of exiles is spoken

In the past tense – quá khứ.

We became nomads, modern cities

are the desert we cross, not so much

for salvation, nor for subsistence:

We cross our endless deserts, looking

For ourselves.”

To which Monique replied: “That desert was an oasis in your company, my friend. Thank you for showing us Viet Am writers how it could be done.”

This sums it up. This desert oasis is what I wish for DVAN one day: to have and hold a space for writers, poets, storytellers, and musicians to gather around a drink and share their soul to those who would listen.

I wrote about Đức and his influence on us in the foreword of the 25th anniversary edition of Watermark: Vietnamese American Poetry and Prose:

“When Nguyễn Quí Đức’s book Where the Ashes Are came out in 1994, I readily joined a small group of Vietnamese American students who offered to help him, mostly by making a show of support at his readings. He welcomed us to his small apartment in the gritty Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco, and after a couple of brainstorming sessions and reading groups, his place would always teem with people talking, smoking, drinking, and eating. It was there, while we were all piled up on his mattress on the floor chatting, with a large painting splattered with red paint floating overhead, that we conjured the extravagant idea of writing our own poems and stories and presenting them to the public ourselves. We wanted to see Vietnamese American poets and writers together on stage, sharing questions and ideas like the events we’d seen at our universities. It was fun to dream.

“At this time, Vietnamese American scholars and artists were not on the Asian American Studies radar because we were seen as too anti-communist and unconcerned with racism. According to Nguyễn Quí Đức: ‘Refugees from Vietnam were then seen as descendants of people in the government of South Vietnam, corrupt officials—and we didn’t fit in the stories of earlier Asian Americans who came from the civil rights movements (while the Vietnamese identify more as Cold War refugees). This accounts for the reluctance of the Asian American communities to accept and welcome the Vietnamese in the beginning until we were seen as a group that could add a voice and strength to the Asian American communities.’ In addition to not being readily included in Asian American activist circles, neither were we invited to established white spaces, because we had not experienced the war as adults, or for those who had, they were judged as failures responsible for the loss of the war. Our numbers were relatively small, and there were also not many established bodies of literary work to be proud of, stand on, or depart from. But when Watermark passed from hand to hand at the gatherings at Đức’s place, the terrain of possibility shifted….

“…We called ourselves Ink & Blood. In the core group was Nguyễn Quí Đức, of course, and also Thien Do, Mộng-Lan, Sonny Le, Thuy Linh, Van Ly, David Nguyen, Hai Dai Nguyen, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Thai-Anh Nguyen-Khoa, De Tran, Trung Tran, Erin Khue Ninh, Cindy Quynh Trang Nguyen, Michael Huynh, and Tu Vu. Nguyen Qui Duc reflects on this time: ‘For many among Ink & Blood membership, the group served as a way to break out of the demands of the community for us to be engineers, doctors, IT tech types…. Ink & Blood faced similar issues that Kearny Street Workshop in San Francisco or the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in New York faced. One was concerned more with promoting community voices from within, the other also interested in getting such voices published and out to a larger readership beyond the Asian American communities.’

“As Ink & Blood, we built a grassroots network of Vietnamese American writers and artists: Nguyễn Quí Đức would find a location (he had connections with the San Francisco Public Library, the Montalvo Arts Center, and the San Francisco Arts Commission) and graphic designer Thien Do would design a flyer, which the rest of us would distribute through email and announcement boards. At these events, we all arrived early to set up and left late after clean-up. In this decentralized process, we searched for poets and writers, such as Andrew Lam, to include in our programs. Since there were so few writers, we ourselves wrote poems or stories for the events. There were no official meeting minutes and no budget, yet large crowds would show up at all our readings. I still recall one event themed around ghost stories. We thought it would be easy, as all of us had grown up with them. We had found a local art center in the Tenderloin that could host. In a makeshift effort to set the mood, we turned off the pale overhead lighting and lit some small candles arranged in a large circle on the floor. The room was full of people, spilling out into the street. As we gathered around the candles to start the reading, however, we were dumbfounded to find out that none of us had prepared an actual ghost story, each of us counting on the other to do so. With this awkward realization, we read whatever we had or improvised. I read an account of a nightmare that I had the week before. Having been taught to never stand out, never speak out, and never tell, we found the process of reading in public both nerve-racking and exhilarating. The audience was supportive of our effort but also clearly disappointed. Looking back, our failed ghost stories night perhaps reflected our unsettled identities, ones that we as migrants were still struggling to figure out…. So we made it up as we went, writing in the dark, hoping that we could really center our own writing one day without fully believing that it would ever come.”

It is no coincidence that our first Southeast Asian imprint with Kaya Press is called Ink & Blood. This imprint in which we are translating diasporic Southeast Asian books into English is an homage to Đức. He will always remain in our heart, our mind and our soul.

Isabelle Thuy Pelaud is the Executive Director and co-founder of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network. She is the author of This Is All I Choose To Tell: History and Hybridity in Vietnamese American Literature and the co-editor of the award-winning Troubling Borders: An Anthology of Art and Literature by Southeast Asian Women in the Diaspora.

Isabelle Thuy Pelaud is the Executive Director and co-founder of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network. She is the author of This Is All I Choose To Tell: History and Hybridity in Vietnamese American Literature and the co-editor of the award-winning Troubling Borders: An Anthology of Art and Literature by Southeast Asian Women in the Diaspora.

Liked what you just read? Consider donating today to support Southeast Asian diasporic arts!