There’s a word I’ve grown wary of. Nostalgia. It is usually deployed within the ever problematic trope of memory politics, enmeshed with a yearning for an idea of the past. Gone, or at least glossed over, is the sharp focus on how collective memory by political actors is remembered, archived, and even discarded. In its place is the tiresome construction of identity through its connection to popular culture.

Writers of a diasporic community raise a lot of these concerns. At once, they are often tasked with writing a story that somehow connects war, trauma, displacement, hardship, and slouching toward a Western dream and land of hope. All of these elements are narrativized for the consumption of an outsider, balancing a historical focus with more intimate family stories. Memoirists are asked and expected to do a lot.

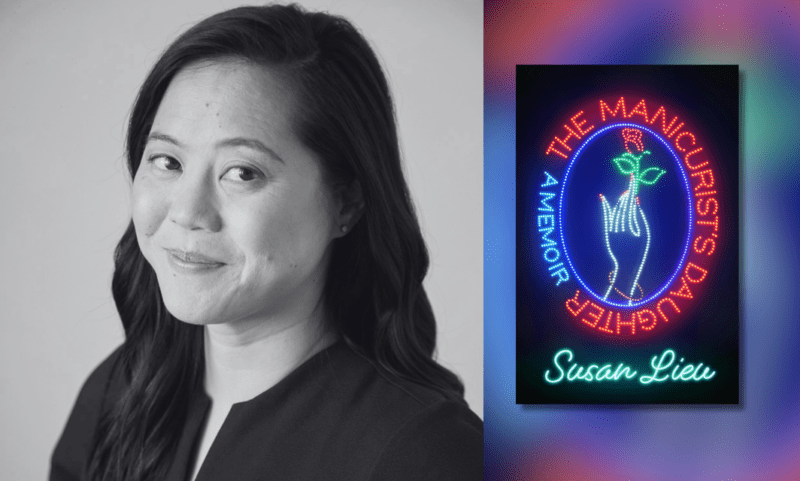

Susan Lieu’s memoir, The Manicurist’s Daughter, reads like an attempt at resisting these expectations. Lieu’s parents were boat people who came to America, and eventually resettled in California, in 1983. Her mother’s death from a botched tummy tuck made them refugees a second time, a sentiment Beth Nguyen also expresses in her memoir, Owner of a Lonely Heart. Lieu’s family stories and histories are told through a particular medical trauma, a starting point to unfold questions of family trauma and uncertainty. Lieu shares that she, at age 38, desired to publish a memoir. The age is significant as it is the same age as her mother passed away because of a negligent surgeon who did not have malpractice insurance. Lieu was 11 when her mother died, and recalls seeing her father unwilling to challenge authority, uncertain of what questions to ask after the death of his wife. This is a typical, heartbreaking scene for many children who grew up witnessing these turbulent moments of fear as an unwanted resident.

The body is a major theme in Lieu’s stories. The body that exists pluralistically, that takes up multiple cultural spaces, the body as a refugee, and as a body that exists in a culture that promotes ridiculous beauty standards. Lieu’s parents proudly owned and operated a nail salon, a status that would make Lieu stand out amidst the legacy children at Harvard University during their painful introductions at orientation. Lieu recalls many of her formative years dealing with her confusion of her changing body. When she first menstruated, Lieu said her mother viewed her body as a burden, merely pulling out some green pads before walking out of the bathroom. Lieu also details a visit at a clothing store in Việt Nam, where the proprietor screams that she doesn’t have size XXL garments. Just existing in her body, Lieu muses, was offensive.

All of Lieu’s personal stories about her own body are contrasted by her mother’s medical treatments to maintain her youth and beauty. In college, Lieu learned words like “capitalism,” “exploitation,” and “intergenerational trauma,” and it was in graduate school that she began to plot her revenge against the negligent surgeon. She’d learned that the plastic surgeon preyed on Vietnamese refugees and boasted that his medical training was practiced on the battlefields in Việt Nam.

Lieu’s depiction of growing up in the ‘90s captures the zeitgeist of Vietnamese refugees clinging to cultural objects. As Lieu investigates this fallen surgeon, she learns that he began advertising his services in the Vietnamese press and that 30 percent of his patients were Vietnamese. Intertwined as cultural artifacts are her references to the popular Paris By Night of Thúy Nga Productions and beauty advertisements. These specific Vietnamese media are not isolated invocations, but instead are used to explore how even diaspora-centered products are complicit in upholding beauty standards. As talented as the women singers are, they also perform to cultural ideals of femininity and beauty under the male gaze. She also mentions the beauty advertisements of Bà Hạnh Phước, surely an obscure name for non-Vietnamese communities, who was one of the show’s biggest sponsors and who sat front row at the live productions. Hạnh Phước was a beauty pageant winner and owner of a plastic surgery clinic in Houston. One of her advertisements was a face wash product, and Lieu remembers seeing a few bottles of it on her mother’s bathroom counter a month later.

Within these family stories is the bigger theme of interrogating justice, an arduous process that appears to abruptly end when Lieu learns the surgeon had passed away from Parkinson’s. This startling realization also brings Lieu to soberly note how vulnerable communities may never receive true justice despite financial settlements. In 1975, the California governor had instilled $250,000 as the value for lives lost during medical malpractice. The value remained the same, never adjusting to inflation. In 1996, the life of Lieu’s mother was valued at that stilted number.

Yet, Lieu explores grief through other ways, by listening to family testimonies, through travels, through investigative work, and through her performance work. The story does not end as Lieu had initially hoped, but there is a reclamation of storytelling and its propositions. Lieu ends her memoir by declaring she is the daughter of manicurists and acknowledges that her stories thus far are only the beginning. This statement should not be read as a cliché, but as a meaningful consideration to how to rewrite our diasporic stories that center our communities in the present.

The Manicurist’s Daughter

by Susan Lieu

Celadon Books, $30.00

Anna Nguyen had been a displaced PhD student for many years, in many different programs and departments at many different universities in many different countries. She decided to rewrite her dissertation in the form of creative non-fiction as an MFA student at Stonecoast at the University of Southern Maine, which blends her theoretical training in literary analysis, science and technology studies, and social theory to reflect on institutions, language, expertise, the role of citations, and food. She also hosts a podcast, Critical Literary Consumption, which features authors, poets, and scholars discussing their written work and their thoughts on reading and writing practices.

Anna Nguyen had been a displaced PhD student for many years, in many different programs and departments at many different universities in many different countries. She decided to rewrite her dissertation in the form of creative non-fiction as an MFA student at Stonecoast at the University of Southern Maine, which blends her theoretical training in literary analysis, science and technology studies, and social theory to reflect on institutions, language, expertise, the role of citations, and food. She also hosts a podcast, Critical Literary Consumption, which features authors, poets, and scholars discussing their written work and their thoughts on reading and writing practices.