Whilst closing in on my research trip to China this December, I made an impromptu visit to Kinmen, my supposed ancestral homeland, where the patriline took off to greener pastures to Singapore. Kinmen just east of Xiamen, is known for its complex and controversial relationship due to the dispute over the political status of Taiwan. Entangled in this Cross-Strait relations between China and Taiwan, I found myself attempting to retrace the footsteps of a certain Seah whose mark has faded beyond recognition and whose mere existence lies in oral accounts passed from generation to generation. Despite several generations of genetic admixture, my brother and I are constantly reminded of the importance of remembering one’s roots in a distant and almost imaginary past.

During my day’s visit to Kinmen, I learnt a few things about the ancestors of the Kinmenese following their move to the island after the Song dynasty. As detailed on the board at the Kinmen Military Headquarters of the Qing Dynasty located in the Jincheng Township of Kinmen, a large majority of island settlers were displaced from various parts of ancient China due to war and political turmoil and decidedly rebuilt their lives there. Amongst these were descendants of fishermen and farmers, pioneers of reclamation, travellers, descendants of soldiers and guards, persons in exile, and those recruited into matrilocal marriages. And so, it seems, Kinmen used to be a place of refuge for renegades across China’s turbulent history and later saw Kinmenese fleeing from the barren land to even better pastures in Southeast Asia.

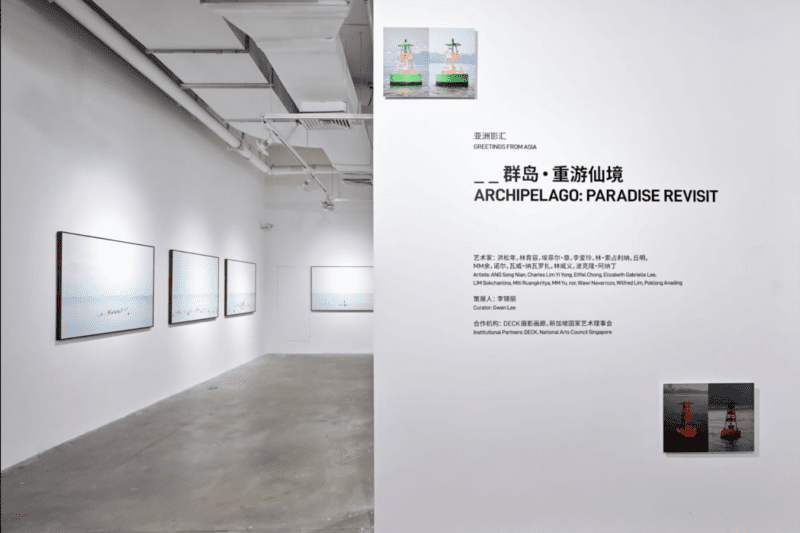

Coinciding this trip to Kinmen with my research visit to Three Shadows Photography Art Centre where the Jimei x Arles International Photo Festival opened in the same week, I stumbled upon Archipelago: Paradise Revisit curated by the founding director of Singapore’s photography arts organisation DECK, Gwen Lee. I soon found myself confronting the plausible and differing paradises of the people before us and the generations after, and importantly, where I stand in the revisiting of an ancestral homeland that people have gotten in and out from for the pursuit of one’s livelihood and probable happiness.

In the brief introduction of the exhibition, Gwen details the running thread throughout the selected works as addressing boundaries and borders, what’s considered in and out of a state, the inner and outer, and the private and public spheres of the social, economic, and political. It further explores the journey to one’s pursuit of paradise across time and space shaped by invisible forces of personal anecdotes, migrant sojourns, and the colonial past, which are marked by geographical traits.

The walkabout started with a sea of heads in the photographic series of Eiffel Chong’s For Such is the Wickedness of the World That It Shalt Be Destroyed by a Great Flood (2015), which reflects on the paradoxical and vulnerable relationship between humans and nature. Through the use of ominous subversion of a seaside holiday, Chong suggests the engulfing blue sea, though there for everyone to enjoy, does not discriminate who it devours in an instant.

Taking reference from the bible in the book of Genesis 6:19, where God revealed to Noah that He would wipe out all land-dwelling life on earth with a great flood because of the pervasive wickedness of mankind, as reflected through the title choice, Chong encourages introspection on the concept of free will in theology where the idea of God’s omniscience and God permitted free will are seen as incompatible. Here in Chong’s work, these humans who, through their own free will, have sought the wild sea as their site of leisure, face the implications of predestination subjecting them to their probable untimely demise, as God had decidedly shown to be capable of in biblical history.

Chong further questions the incompatible relationship between humans and nature, where the cyclic intertwinement is inequal because nature is calamity in disguise at God’s beck and call and humans cannot absolve themselves from their wicked ways until they have redeemed themselves.

Circumscribed within the paradox of free will, where all are subject to predestination, I navigated towards Charles Lim’s SEASTATE (2015), which examines the invisible sea boundaries and occurrences surrounding Singapore. Photographing the maritime buoyage system that defines national and international boundaries in territorial waters, Lim observes the human agenda on resources and land along with a narrated interview with the “Sand Man,” who worked as a sand surveyor in Singapore during the 1990s and transported sand for land reclamation. The “Sand Man” further illuminates Singapore’s intricate relationship with the sea while exposing the inherent ambiguities and paradoxes in its efforts to assert ownership. In what seems like the limitless sand and bottomless seas lies the corporatisation of territorial waters.

Yet beyond just seeing the sea as a barricade, Lim encourages audiences to seek respite and refuge in the warm tropical waters. Instead of fearing its power and living divided from nature, accept it for what it is and seek solace in its existence.