Art Essay On Visiting ‘Where The Sea Remembers’ at The Mistake Room, Aug 2019

As myself an artist and writer of the Vietnamese diaspora, one of the things I find myself craving when I encounter art of our diaspora is a sense of, what I will call here, being inside. I want to encounter other interiorities of diasporic humans—individuals—with intimate views and experiences; I want to feel validated and resonated on the level of the subtleties of our existences, and not defined—seen/see-able—only according to the broad strokes that mark our politically or culturally locatable existences: as children or descendants of war, as refugees, as trauma-inflicted beings, as racialized Asian bodies in America, as non-belonging and in need; as long-sufferers and victims, in short. We may be or have been all of those things to varying degrees, at times, yes, but what about, also, our intimate, our individual, selves and bodies and beings? What about our particularities of sight and sense? What about how the light falls for each of us, over any ordinary or extraordinary landscape, and how it is received behind the eyes and within the deeper self? How does that feel? This is what I find myself craving to encounter in diasporic art these days.

It is a known argument, certainly, that Vietnamese and other minorities have been degraded—dehumanized—as presented through the lens of much of the art (that references Vietnamese or Vietnam) made by white Americans; and thus follows the solution that this must be rectified by an art that humanizes us—an art that should also center our own voices and visions. We should be afforded art that conveys our stories, represents our images on our terms. In truth, there is and has been no lack of this art being made by Vietnamese people in the diaspora, for decades now, in the US and other countries, and in Vietnam. It is only the failure of the American imagination and perception—a failure and inability to recognize and make space for the full imaginative agency of Vietnamese visions—that has perpetuated the notion of a dearth or naivety of art of the Vietnamese diaspora. The gatekeepers in America (more often than not, white)—curators, editors, publishers—have long been invested in a narrative of the lesser Vietnamese body, one in which the Vietnamese story is comprehensible only once it is grafted onto the “American” story which, tiresomely, is that one again about war and power and conscience. In this dynamic, Vietnamese people and Vietnamese art become visible and relevant only if and when they/we make reference to the American travesty of its war in Vietnam and that war’s aftermath, only when they/we are presented (or present ourselves) as a form of collateral, in short.

There have not been many major exhibitions of Vietnamese art or artists in America to date. Among the most visible have been artists such as Danh Vo—whose exhibit at the Guggenheim in 2018 contained found objects that connect literally to the U.S. “Vietnam war-era” administration (i.e. armchairs bought at an auction of the personal memorabilia of Robert S. McNamara)—and Dinh Q. Le, perhaps best-known for his “woven photographs” of imagery from American war cinema and documentary images, as well his manipulated images of U.S. military helicopters falling into the sea. These artists’ works are impactful and exceptional on their own terms, no doubt, and contain many layers of intent and meaning. However, I think it may be observed that the legibility of their art, for audiences in America especially, has relied on those factors in the artworks that acknowledge Vietnam as a subject of war, colonialism and empire—that is to say: that recognize the power dynamics that have entangled America and Vietnam.

While these matters addressed via art are no doubt important—and I am a fervent admirer of these artists—it yet rouses in me a further line of questioning. By now, I understand who I am and how I am perceived in relation to war and western power structures, am aware the many convolutions and complexities of this bind. But: who are we beyond the question/identifying factor of war? How do we/do we exist (apart from that war)? In our own eyes; within the vehicle of our own bodies; in reference to one another in and across the diaspora?

*

Where The Sea Remembers, an art exhibition and “interdisciplinary project” at The Mistake Room in Los Angeles (July 13-Oct 12, 2019), makes an earnest, modest, and thus respectable effort to open doors onto some of these questions. The exhibit description wisely does not prescribe itself as a “comprehensive survey” on contemporary Vietnamese art, but rather “a series of dispatches” from the contributing artists. By intention the project “acknowledges and embraces incompleteness in an attempt to re-imagine the function of the regionally-based exhibition format” and “considers the nation-state not as a static geographic locale or even a diasporic abstraction, but rather as a complex set of tense and evolving individual relationships between people and their ideas of a homeland.”

This seems a good beginning point, a circumspect manner of entering into a territory one is aware (the curators as well as probably many audience members, both non-Viet and Viet-Americans, I suspect) that we/they are just scratching the surface of, in regards to encountering Vietnam and its diaspora in relation—not just to America—but also to itself, to all its variant and scattered parts, places and spaces, today and ongoing.

Where The Sea Remembers is a group exhibition of 15 artists and collectives from Vietnam and its diaspora, including: Truc-Anh (HCM, Paris, LA), Ngô Đinh Bảo Châu (HCM), Vo Tran Chau (HCM), The Propeller Group (HCM), Nguyễn Phương Linh (Hanoi), Sandrine Llouquet (HCM), Thinh Nguyen (Los Angeles), Tuấn Mami (Hanoi), Trong Gia Nguyen (HCM, Brooklyn), Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn (HCM, Los Angeles), Nguyễn Văn Đủ (HCM), Phan Thảo Nguyen (HCM), Thu Van Tran (Paris), Trương Công Tùng (HCM). The group includes artists from Vietnam as well as artists based in the diaspora, some who live and work both in Vietnam and in the US or France. The show’s title makes reference to a song by Trinh Cong Son, “Biển Nhớ”, or “The Sea Remembers”, thus aptly tapping into motifs of water and memory that are certainly prevalent in art and literature of the Vietnamese diaspora. Beyond the foundational premise of Vietnam and diaspora, however, no central theme entirely guides this exhibit, which is an aspect I appreciated. Differing from other curations I’ve seen that tend to summarize or validate Vietnamese art by how effectively—this often means: disturbingly—it references the Vietnam war and its aftereffects, WTSR instead allows “artists’s interests [to] function as the structuring devices that organize the presentation of works in the exhibition.” In short, this means the exhibit allows space for the intimate and the individual—the varying interior—concerns and questions of its artists.

This may make the exhibit a little harder to read, a little less legible, for some audience members. But this is also to be expected in such a context, where the context for comprehension is still evolving, still in a sense being dispatched.

In Ngô Đinh Bảo Châu’s “The Extracts”, where the artist captions his painted images with flat visualizations of braille, layers of evocation about legibility lay latent and virtually inaccessible here. Why does the artist choose to portray braille—a language for the blind—in a format that must be seen to be read? For whom is this convolution of language-play? And (how) is it even meant to be readable?

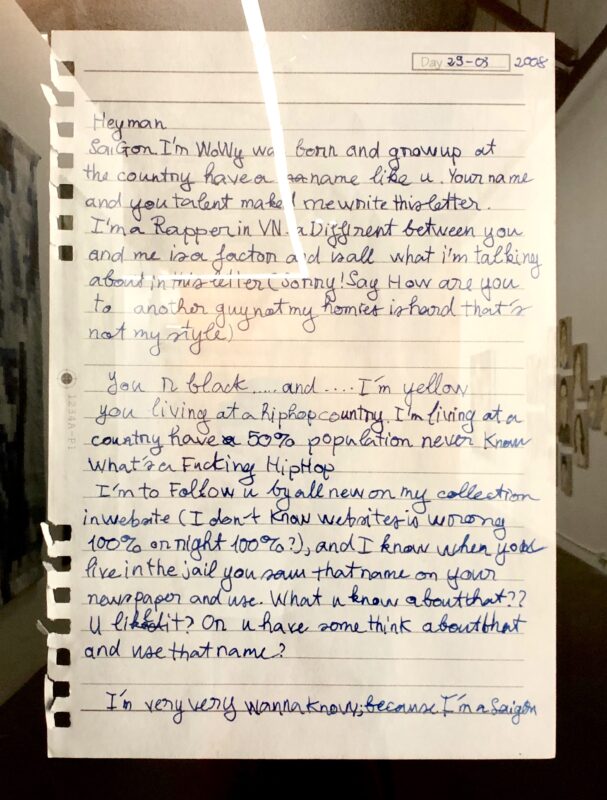

In Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn’s Letters from Saigon to Saigon, legibility and reading/(playful) mis-reading also come to the fore, through a series of blown-up photographs of Vietnamese rapper Wowy’s handwritten letters to an African-American rapper who bears (we assume by self-naming) the same name as the Vietnamese rapper’s home city: Saigon—thin tendrils of connection and odd vyings for comprehension are sought in such pieces.

A sense of meaning and material being both transparent and layered—weaving obscuring and haunted effects—was apparent in several pieces, from the gold text printed onto translucent pieces of fabric dyed in soil from the Central Highlands, covering two walls in Truong Cong Tung’s Traces of Infinity; to Phan Thao Nguyen’s Voyages de Rhodes, watercolor drawings gently depicting the artist’s own renditions of history painted over the text of pages torn out of seventeenth century French missionary travel books; to the portraits of family members draped in white veils of Phang Quang’s evocative and performative photographs, Re/cover, that offer up an embodied archive of Japanese military engagement and interrelations with Vietnamese after WWII.

There is a lot going on within and amid the disparate and very individual voices, motives, and underlying influences feeding into the artwork of Where The Sea Remembers. The artists make reference to numerous points in history and to the present-day, from varying vantage points—shores—of the diasporic and Vietnamese experience. One needs to delve deeper to truly fathom the particular points of reference and region each of these artists are working from—which is something The Mistake Room’s accompanying website on the exhibit makes possible, fortunately extending even beyond the exhibition dates. From here, one can begin to learn more about each artist’s practice and individual locus. The result is no less than the realization—a re-wiring, for some of us—that the contemporary Vietnamese experience is a multifaceted, multi-focused, richly complex “sea” of memory and history and personal experience. The interiority of each artist is given space in this exhibit, which requires both patience and curiosity to encounter and decipher.

Affecting to the traveler-heart in me was Thinh Nguyen’s Across the American Plains, a series of paired square-framed photographs and an accompanying journal of travel notes. While the exhibition materials described this piece as a document on “how one comes to know a nation”, I read the images also as landscapes intimately observed from within the diasporic traveler’s body, and for me this evoked a sense both intimate and vast, of the closely held and of the ungraspable—landscapes literally inhabited by the body (textures of different beds’ beddings) juxtaposed beside glimpses of external landscapes of the American nation (abstracted trees, blurred horizon lines, etc) observed as if through the blurred film of one’s eyes, the sense being of a vantage point definitively within and embodied, emanating a subtle, humanizing quietude.

*

As its project description emphasizes, Where The Sea Remembers serves well as an entry point to larger, and still evolving, dialogues. I came away from this exhibit appreciative of having encountered an exhibition of Vietnamese contemporary art that did not rely on references to the Vietnam War or its aftermath, nor to American artists of that era, in order to orient its viewers. I also appreciated that the exhibition combined Vietnamese artists in the diaspora alongside Vietnamese artists from Vietnam—it is important, I believe, to include diasporic artists next to native Vietnamese, to recognize the interconnections amid and across our diaspora, and to not draw any deeper those lines of separation between our so-perceived circumstances or regions (which are, in truth, categories born out of the violences of nation-states), nor to exoticize “native” or “heritage” culture over diasporic.

I also felt that there is room, yet, for more and more varied acknowledgments of contemporary Vietnamese artistic perspectives to occur, and especially perspectives from different parts of the diaspora. I still long to enter spaces that resonate deeper diasporic interiorities, in all their variances and vagaries and nuance, across and irregardless of distances and borders and assumptions.

Visit The Mistake Room’s Where The Sea Remembers website to explore more on these artists.

Read the LA Times review of Where The Sea Remembers.

Read Eastwind E-Zine’s review of Where The Sea Remembers.

CONTRIBUTOR BIO

Dao Strom is the author of the books You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else, We Were Meant To Be a Gentle People, The Gentle Order of Girls and Boys, and Grass Roof, Tin Roof; and a song-cycle, East/West. She is the editor of diaCRITICS. www.daostrom.com