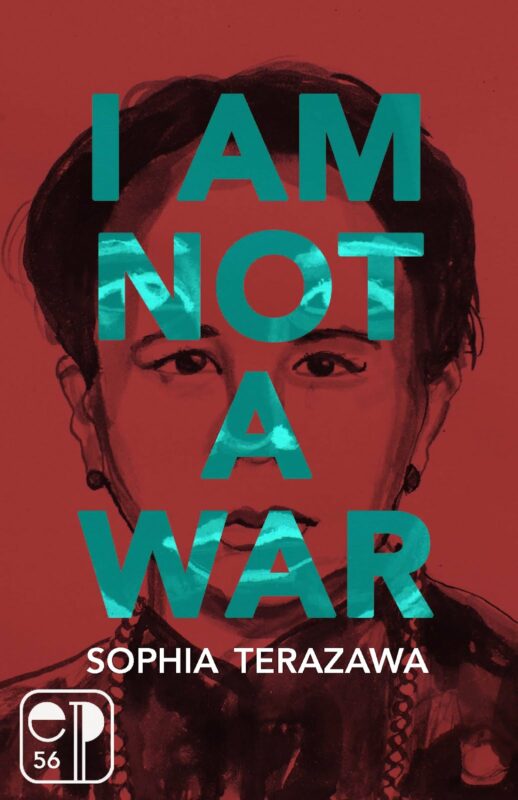

Sophia Terazawa was featured in our OUT OF THE MARGINS series in 2015 where we published a hybrid poem. Here she speaks with Vi Khi Nao about her debut chapbook I AM NOT A WAR, her practice, writing like a tree.

VI KHI NAO: Your table of contents from I AM NOT A WAR is a poem in itself. Did it arrive to you in this fashion or was it born from a place long before the chapbook met you eye to eye? Body to body?

SOPHIA TERAZAWA: Oh! I love that we’re starting here (and feeling a little sheepish, too, but let’s try!). When writing the chapbook, I had a clear idea of the “scaffolding.” This means the bones of the book were ready in my mind: Title Page, Table of Contents, Appendix, etc. Yes, it absolutely became an “eye” meeting my eye! The empty eye sockets out of which the book had to face itself. The “Table of Contents,” then… [pauses dramatically to think] came out of what I can only call, right now, my way of “feeling” forward. In simple terms, the poem came after the “section heading,” which already felt violent and so celled-in with itself.

VKN: Did you have a hard time finding a home for your marvelously hybridic chapbook? Can you talk about the process of it being born? And, also how long it took you to write it? I don’t know why I had the impression that it took you roughly 5 years. I have no measuring stick of time for this estimate. But I thought to throw it out there.

ST: You’re so kind!!! I’m feeling embarrassed, really. [grinning] [gets up for a cup of water] My friends who know me know that I am both four years old and four-hundred years old. So when I get nervous (or excited) I start panting heavily out of my mouth. Like a Panda. The chapbook found its home, also in this way. Running out the “door” on tiny, tiny legs. I “completed” the chapbook at the end of 2013. My mind was in a different place then. I wrote most of the text for I AM NOT A WAR as my final project for a “historiography” class at my college. It was a small class, and I was the only person of color, so, naturally, I felt caged and had moments of quiet implosions “at the table,” so to speak. We were supposed to turn in a traditional essay at the end of the semester. Instead, I turned in this kicking, screaming thing (with pictures!). The timeline, after that, after graduating in 2013, feels blurry to me. Maybe the chapbook took longer to complete itself. I sometimes don’t think it’s done. I sometimes want to re-write it entirely. Or make a new companion text. But the chapbook was finished about a year later, and then sent to the Essay Press chapbook contest. I really liked their digital work, I remember. However, I don’t quite remember the exact moment of “submitting” it. At the time, I was living in Kolkata with my then-partner. I was very depressed.

VKN: Why were you depressed, Sophia? What about being the only person of color made you feel caged?

ST: [a little girl looks into her cup of water and blows a bubble] I’m very old. I think I felt my “old-ness” for the first time, deeply so, in 2013 [stops to look up the year]. In the year of the Snake. Ah! That’s my year! By returning to my zodiac, I fell into a crisis. But worst of all, I didn’t know how to speak about it, except through my work, poetry mostly. In the U.S., especially, I often find myself in spaces–more and more–where the static becomes too much for me. In 2013, in particular, I felt it. The static. In that room of “historiography” the energy around how history must be written felt false, especially around the subject of colonialism and de-colonial practices beyond the walls of academia. I felt too many eyes on the text. I couldn’t breathe.

VKN: How old are you? The kind of work you do feels timeless. Perhaps you miscorrelate oldness with timelessness? What does it feel like to be a snake?

ST: As of typing this now, I like to say that I am 430 years old. 🙂 Now I’m curious to know your zodiac, too! And I appreciate how you ask about the separation between the two–age and time. Like an oak in comparison with the arms of a bug. They’re two different things. Yes, one lasts in a different span of “time” compared to the other. Maybe I feel like the tree, having been in one spot for too long, seeing the wars, breathing in…breathing in. I used to be ashamed of being a “snake.” Especially with its association with vanity and other egotistical traits. But I’m learning to also let her protect me, when I need her the most. To be in the water, curled up, asleep.

VKN: I am sheep (Sheep Machine !) Do we get along? A snake and a sheep?

ST: [thinking] Yes. 🙂 Yes! My mother would know more. She deeply believes in the “signs” of these years, and how certain energies should or should not fit together.

VKN: Are you close with your mother? Has she read your manuscript called I AM NOT WAR? Your title made me think of my manuscript titled: WAR IS NOT MY MOTHER. Thus, the mother question. Perhaps we were both inspired by Lê Thị Diễm Thúy’s poem with a memorable refrain: VIETNAM IS NOT A WAR?

ST: Yes! Yes!! The refrain to that poem still beats in my heart. Most thunderously! I feel the vibrations with those words. I can see my mother’s eyes flaring with the spark of survival. She survived, she once told me, so that she could one day meet me. It makes me weep. She looked through I AM NOT A WAR once, before sending it to my aunties who could help translate some of it for her. My mother’s English is okay. It makes the question of closeness complicated.

VKN: Why does it make the question of closeness complicated?

ST: There’s an ache on the right side of my chest, under the bones. We call each other a few times a week. The conversations are brief: How are you? Are you eating? We take turns asking each other the same questions and providing almost the same answers. Things are okay. Today I’ll eat some soup. We become mirrors of each other. I’ve been learning Vietnamese (through an app). Last summer, I tried to say something to my mother in Vietnamese. She became so unnerved and told me to stop, so I did.

VKN: One of the most exciting aspects of your work is your acute and adept relationship with images. I noticed on page 40 of your chapbook, Agent Orange has been criticized visually (you drew that fruit orange wheel, yes?) and how through this raw and minimalistic translation, you managed to alter the discourse of this particular destructive defoliant chemical that destroyed/continued to destroy an important ecological landmark of Vietnam. I love how you married the two aspects of your Asianness (Vietnameseness/Japaneseness) in your work and created an intense conversation of beauty, perversion, and war (its impact) on one’s literary soul. If you are not war, are you history and biography? What kind of anachronistic body are you? And, what do you hope to achieve through its declarative negative inversion?

ST: Oh, yes! My stencil drawings! [makes a face like the *glasses nerd emoji*] Yes, it was very simple in my mind. I would need to find an “orange” on the Internet to trace with my colored pencils. On top of that, the letters would be traced. I’m glad that you pointed it out as a “wheel,” which I haven’t thought of before! For me, the physical act of “tracing” (in the dark, in the closet with just the illumination of my laptop shining through a white sheet of computer paper), I recall wanting to take the time to “trace” the images that have otherwise been reduced to concepts in the post/colonial imagination. If I could just draw it, simply, for what it is–I thought to myself–perhaps … [my tiny Panda just woke up!!! He’s waddling across the room now. Wondering what I’m doing.]

Perhaps it would be clear what the impulse of “naming” could do in ways that simply writing out the words cannot. We can’t name the horror. We can trace it. We can color in the lines. But to name it outright? [My tiny Panda nods. Rubs his eyes.]

VKN: Your sense of humor is also one of the most poignant aspects of your work. The Yellow Face text on a blank, white rectangular was really clever. The plethora of faces collaged on the photograph on page 36 with title, “ON HISTORY THREE WITHOUT TRANSITION,” and other satirical ones. It’s quite remarkable of you to be able to convert a potential caption into a title and vice versa. What is your relationship to subversion? Do you believe in it? Do you think it could be a rhetorical tool to turn war and literature and photography and art on its head? What do you hope your work could achieve with it? (Hello Panda ! Welcome to this conversation! Come join us and have literary tea with us)

ST: Oh, wow! I’m so glad that you found the rectangular passage satirical! At the time of “making” them, I was actually full of rage. In my mind, I had a film sequence of frames, of literally me, the faceless body running, from behind, and then from the front. I was frustrated because this came out of the impulse to make “real” my mother’s escape from Vietnam, a sequence of events that I can only sense in my mind (and running body), though never “clearly” on the page. For me, it feels as though the speed of flight is a crucial part of a shared identity (with my mother). Like the barrels of Agent Orange dropped into a field, my mother soared from the country. She’s a bird, in my mind. But I can’t “draw” her. It wouldn’t be right to draw her. So I simply made the “frames” of a film that will never be made. I also believe in subversion as much as I believe in what tools I can lay at the altar–little stones, rose petals, and other trinkets to appease the gods.

VKN: It begs the obvious question: does writing the word “Yellow” make it yellow or more yellow? Or does it return to its white form? Whitening its yellowness more? What do you think of the whiteness assimilation/fixation/fascination? What do you think is the greatest asset for being white?

ST: I think about these questions in relation to blackness! The text is black. The space is white. I’m somewhere in the middle, on an axis of power and disempowerment. How the font is “read,” becomes, I think, a test over time. I really appreciate how you brought up the question of timelessness earlier. This makes me think about the acceleration required in the assimilated body–to blend in, learn more quickly, and stay. Settle.

VKN: What is your favorite page/passage from the chapbook? Do you frequently return to your manuscript and ask it, “How was your boxing match with history?” or “Will you let my toilet paper cry on your shoulder?”

ST: Now that I AM NOT A WAR has become too tall for me, by means of time multiplied by distance, I feel like her benevolent auntie whenever she chooses to come back home (which is quite rare). The chapbook has taken up smoking cigarettes and riding a blue Vespa cross-country. Sometimes, I’m embarrassed to say, I completely forget about her for months until someone else brings her up! She fights her own fights now.

VKN: Are you more of a bamboo person or more of a bell pepper kind? What talisman expresses your philosophy on poetry best?

ST: 2,000 percent bamboo! I especially like it when my mom cooks the baby bamboo shoots until they’re the perfect balance between soft and crunchy. My talismans are like this, too. Panda is very brave. But he’s also nervous about the state of the world, in general. I have an Anxiety Bee named Bee who helps me do my taxes. In terms of expression, I feel the talisman has no body. It is a spirit. Sitting on my shoulder. Or sitting in the kitchen sink, playing around with a fork. It would be too big to call these spirits “guides” or “ancestors,” because they’re often little children. I find that children ghosts tend to find me. Or I tend to see them more easily than others.

VKN: Clearly, I just want you to reassure me of your intense affinity to the panda :). My favorite passage from your chapbook exists in the last three or so pages of your manuscript (its ending). Can you talk about that end section? Would you ever rearrange it so it appears in the middle? (Personally, I think it is apt and perfect where it is at…) But sometimes our future changes the way we have arranged the content of a particular body of work.

ST: I feel very honored. Panda, if he could blush, is also very humbled. Sometimes I get sad when people treat him like a joke. Or worse, like some symptom of an illness to be politely ignored. The ending of I AM NOT A WAR serves a similar purpose, too. An illness that I can’t ignore–simultaneously mine and part of a larger system. I’m not sure if I would arrange it. I have to confess something. I delete everything I write. Notebooks, too. Perhaps I got this trait from my mother–to suddenly, and frequently, uproot and leave everything behind, in a giant fire. So, I don’t have any remaining manuscript or records of I AM NOT A WAR. I just have the PDF that is available online. So if she chooses to re-arrange her limbs, that will be entirely up to her.

VKN: The body seems like an important theme in your work. Why is that? Speaking one particular body part: normally, I am not too much of a fan of photos that depict someone giving the middle finger, but I thought the photograph on page 16 was absolutely remarkable. I believe the context and the semi-expressionless facial articulations of all the females in the black and white photograph contrasted very well with its nonchalant “fuck you.” We Asian women are often depicted in Western cultures as being demure and “polite” as in “obeyable” and not defiant and I believe that photograph exhibits our Asian femininity in the most understated gutsiness. How do you feel about this photograph? It converses so well with your work and is timely too.

ST: This is one of my favorite photographs! The photographer, Mike Murase, was an activist and co-founder of GIDRA (1969 to, I think, 1971), an Asian-American focused newsletter which strived for a complex, intersectional approach to anti-racism and anti-imperialism (the two can’t be separated). I wanted to make sure that the murmurs of dissent did not happen within the confines of a text, a chapbook. These conversations, both nonchalant and defiant at the same time, happened, continue to happen–across time and space.

VKN: What are you working on now, Sophia?

ST: Right now, I’m working on my heart. I want to be loved, deeply. It feels weird to say (aloud, with Panda as my witness), that I’m also working on my “self-worth.” I’ve been going to a lot of therapy lately. Outside of that, through my poetry, I’m working on a few collections. They’re all skin and bones at the moment. But I have many friends who care about me. For this, I’m grateful. [Panda waddles outside to check on the hummingbirds.]

VKN: If someone were to offer to give you a house with as many bathrooms as you like? How many bathrooms would you like? And, would you ever use a hair blower to warm up a plate of sushis or bánh mì?

ST: I just want one! One toilet. One shower. My dream is to one day live in the woods, near a mountain, near a lake. It will have one bathroom. One kitchen. One bedroom. And if I’m lucky, a living room that has a nice window view. The grandchildren of my friends will come visit their Auntie Sophie. And I will be very happy. I’ve used a hair blower to warm up several things–socks, a toothbrush, ceramic–but never rice or bread. I wonder if it would get soggy? Would the air droplets gather at the edges of the plate? Hmmm… Recently, I was in Slovenia for a summer residency, and it rained most days while I was there, for the first half of the month. I didn’t have any hair dryer, so all my socks had to be scattered around the apartment.

VKN: I like how decisive you are with your domestic amenities. How are your teeth? And, your hair? I based this question on this old Vietnamese proverb: Cái răng, cái tóc là góc con người.” Basically, I am asking: how is your soul? Is it still there?

ST: Oh my gosh. My mom asks me all the time about my teeth. She’s extremely worried about the nature of my teeth. She has this fear that one day I will suddenly lose them all at the same time (which is what happened to her, on the boat). She rarely asks about my hair, though. I think it’s because I have my father’s hair, which is coarse and heavy in parts. But I’m really touched that you asked this. Once we get to know each other more, I might check in later to ask about your heart, and your family. And if you’ve been eating well. My soul is many.

VKN: Did you like Slovenia, Sophia? The country rhymes with your name, sort of.

ST: Yes! Very much! I like to say that it was the Most Romantic Time of My Entire Life! Oh, yes, it was very, very romantic. Panda and I wish to go back one day, if we can get the funds, again.

VKN: If you were to change your “wardrobe” during this interview? Which question of mine would you proceed to alter the pajama of this conversation?

ST: It’s strange. I was so determined to have a costume change at the start of this interview, but as I fall deeper and deeper into your incredible thoughts and questions, I find myself sinking into my clothes, like a second or third skin. I’m also being careful about speaking aloud as I type to be as close to my “speaking voice” as possible. I used to be ashamed of this voice. As though it took away some part of my intellect and hid it under a rock. But I let her speak. She often takes off her clothes at performances. So maybe, next time, a bell.

VKN: What book you are reading right now that you would be excited to donate to Goodwill?

ST: Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking. I have mixed feelings about it. The feelings pour into a bowl and turn into twelve cupcakes. I’ve also been re-reading The Lover by Marguerite Duras. Both, white ladies.

GIVE ME REFUGE (1995) | Family Reunion in Vietnam, a film by Sophia Terazawa

“In Vietnam,” the narration begins. “It is November 26th. 7:33 A.M.” The voice is that of my father, a Japanese man who holds the camera. He speaks in his careful, observant English. “It is very early morning. Sky is overcast. But very, very pleasant.”

In the next scene, my father is in front of the camera. He’s instructing my mother, a Vietnamese refugee, to speak about the hotel standing behind him. “I don’t know what to say,” she laughs.

What you don’t see in the frame: my hand behind the film, cutting these two scenes of my parents together, many years later. First, a family strolls across the sand of a beach. My mother’s just returned from exile, from America, in 1995, with her Japanese husband and two bewildered children. I’m pissing in the grass with the help of my mother. My cousin and little sister watch. Then we’re at the graveyard of an ancestor. “Jungle,” my father observes. “Jungle, everywhe–”

I cut the scene.

What was most difficult about making this film, as the daughter of a refugee, was a matter of time. In other words, how could I render my mother’s first return to Vietnam, from a journey she wasn’t supposed to survive at the end of a war? And at what cost?

“Are we safe now?” I also ask as a child, at the beginning of the film. Perhaps I mean to ask, instead, “Are we still in exile?” Perhaps by the end of making this film, “Give Me Refuge,” I’m not sure of my answer. And who I’m talking to. Maybe you can decide.

*Note: The opening and closing scenes of “Give Me Refuge” are from a “60 Minute” special, documenting the Vietnamese refugee experience, my mother’s experience.

Contributor Bios

Sophia Terazawa is a poet of Vietnamese-Japanese descent. She is the author of two chapbooks: Correspondent Medley (winner of the 2018 Tomaž Šalamun Prize, published with Factory Hollow Press) and I AM NOT A WAR (a winner of the 2015 Essay Press Digital Chapbook Contest). Her poems appear in The Seattle Review, Puerto del Sol, Poor Claudia, and elsewhere. She is currently working toward the MFA in Poetry at the University of Arizona. Her favorite color is purple. sophiaterazawa.com

Sophia Terazawa is a poet of Vietnamese-Japanese descent. She is the author of two chapbooks: Correspondent Medley (winner of the 2018 Tomaž Šalamun Prize, published with Factory Hollow Press) and I AM NOT A WAR (a winner of the 2015 Essay Press Digital Chapbook Contest). Her poems appear in The Seattle Review, Puerto del Sol, Poor Claudia, and elsewhere. She is currently working toward the MFA in Poetry at the University of Arizona. Her favorite color is purple. sophiaterazawa.com

Vi Khi Nao is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018), Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), the short story collection A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016, the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), and the poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others; her interviews with writers have appeared in many publications as well. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University, where she received the John Hawkes and Feldman Prizes in fiction and the Kim Ann Arstark Memorial Award in poetry. vikhinao.com

Vi Khi Nao is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018), Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), the short story collection A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016, the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), and the poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others; her interviews with writers have appeared in many publications as well. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University, where she received the John Hawkes and Feldman Prizes in fiction and the Kim Ann Arstark Memorial Award in poetry. vikhinao.com