Claire: You’ve been thinking and writing about beauty and fashion for much of your scholarly career, from your first monograph The Beautiful Generation: Asian Americans and the Cultural Economy of Fashion, which was published in 2011 to the co-edited collection, Fashion and Beauty in the Time of Asia, which was published in 2019 to your most recent book, Experiments in Skin: Race and Beauty in the Shadows of Vietnam. You’ve also written about popular culture and digital media and technology in two other very prominent co-edited anthologies from earlier in your career, Alien Encounters: Popular Culture in Asian America, which was published in 2007 and Technicolor: Race, Technology, and Everyday Life, which came out in 2001.

Can you tell us about your arrival to the project that became Experiments in Skin and how you see it building on and speaking with your past work and scholarship, and also perhaps, turning to something different and new?

Thuy: That’s such a good question and a generous one. It also reminds me of how old I am! In some ways, I felt like the book found me rather than me finding it. There was a lot of experimentation, trial and error, in this project. But, as you were mapping out my scholarly trajectory, I realized that this experimentation sat on a lot of work that I had done before in thinking about the relationship between race and labor and aesthetics. I have long been interested in the ways that studying everyday engagements with objects or practices that we think of as feminized and thus degraded can open us up to big questions about our economic life, our world-making practices, about how we understand ourselves in relation to our history. I think I was always interested in trying to figure out how people engage with these banal objects—a lipstick, a scarf—as a way to articulate questions that are maybe hard to pose or to talk about. I think that’s what this book sits on.

But when I was doing my research, and I say this in the book, there were a lot of twists and turns and a lot of finding my way through questions that I didn’t even know I had. I started this project thinking that I’m going to do a study of luxury consumption in a post-socialist or a late socialist state. And I go to Vietnam to do this. And then it turns out—and maybe I should have already known this—that all the things that I’ve read about what consumption is, either as a tool of domination or a way of expressing certain kinds of agency, were true, but did not fully set the terms for what the people that I met there were endeavoring. The project really took off when I realized, actually, I was less interested in consumption as an abstract practice than in the emplaced and embodied question of: “What was consuming these women?” And what was consuming them was partly what was going on in their present worlds, but also what happened in their history. Once I realized that, I had to return home, and turn to the archives, because I couldn’t understand what was consuming these women through an ethnographic mode alone.

Claire: That’s so remarkable because I think what you’re also pointing to in the shift that happens in your research and in your questioning is also profoundly a shift in method. And your methodology is really one of the most striking dimensions of the text. I know it’s one of the dimensions that my peers, friends, colleagues, and I really take up and think deeply about. There’s something that’s just so prismatic about your methodology—the way that you bring ethnography, archival research, and intimate close readings of cultural texts and historical artifacts all together. What I find so animating about this sort of collection of methods is the ways that they all synergize together. They feel equally vital. They’re actively hammering something out. And I’m wondering, how do you see your methods speaking to and collaborating with each other? Why was it important for you to tell the story about beauty, race, and war using these particular methods?

Thuy: Well, like yourself, I was trained as an interdisciplinary scholar. And though I have a degree in American Studies and was taught to appreciate the convergence of different methodologies and to be capacious in thinking about all the tools that I can bring to my research, it wasn’t until I was confronted with a social reality that was hard for me to figure out that I realized what that really meant. This is to say that it wasn’t that I set off to do interdisciplinary research necessarily, but that I was confronted with a set of questions I could not answer through a single method alone. I was confronted with problems that really forced me to take up multiple tools.

Having said that, I’d never really spent the amount of time in the archives that I did for this book before. And I gained a really deep appreciation for the work of the historian through this—how elucidating one document can be, how tedious sorting through boxes of them is. For me, these methodologies had to work together because they had to help me tell a story that I couldn’t tell without all of them. For scholars like you who are trained in this interdisciplinary work, I think it’s such a boon to you because these methodologies will not seem unfamiliar. They won’t seem entirely scary. Even though it is a very different process to go and do the deep archival work, to do the deep ethnographic work, to do that kind of visual analysis, it’s part of the water you swim in. It’s actually part of how you’ll learn to see the world.

Claire: That’s so helpful, especially for me now at this particular stage where I’m figuring out my methods and trying to attend to them as more than just something that I pick up and put down. But rather, really thinking about how they get stitched into the project, how they actually become, in many ways, the project itself. What’s so profound about Experiments in Skin is that the methods are the story. It’s about what you see and what you don’t. And then, therefore, what kinds of tools and approaches you use to surface those ghosts.

Thuy: Absolutely. One of the things I also learned is that people are always inventing their own methodologies. Part of this book is about how Vietnamese women practice science. How they’re not outside of it, even as they pose a challenge to the kind of science that these dermatologists and military scientists were engaged in. They use things like “popular epidemiology,” they offer ways of knowing the body and knowing their environment that are deeply methodological, [for instance,] how to use touch as a way of knowing skin. That really helped me to understand what a methodology is: it’s a way of doing things. And a way of doing things is also about a way of conceiving the world. These are not separate at all.

As researchers, we are, at our root, trying to comprehend something, to understand some problem. We’re using the tools that we have to help us do it. But the truth is everyone’s trying to understand the world that they’re living in, right? And everyone is developing different tools to do it. How do these work together? How can we learn from these different kinds of methodologies and different ways of knowing?

Claire: I love that so much. And it reminds me of two things. Firstly, it reminds me of the ways that Trinh Min-ha thinks about interdisciplinarity as not so much this question of accumulating expertise of different specialized knowledges, but as one of breaking down and shifting the very borders of these different knowledges. What Experiments in Skin does and what you do and what the women in your book do is disintegrate and dissolve what we think of and what we know to be science and history. In these moments of disintegration there is also, as you write in the book, these real pockets of world-making, of small freedoms.

Secondly, and still staying with methodology, I’m also reminded of the work of translation in this book. You write that Experiments in Skin is at once a ghost story, a skin story, and a war story, which, as you show us, is fundamentally a story about beauty. This is such a striking formulation. And I sat with this for a really long time, trying to make sense of how we come to know war and remember war, and how this intimate knowing resists a kind of sense-making legibility; it requires a certain kind of translation. Here, I’m reminded of how Anna Tsing describes translation as a “messy process” of “jarring juxtaposition and miscommunications” that create “patches of incoherence and incompatibility.” And I’m really interested in whether you encountered such moments of incoherence and messy translation when researching and writing the book. And more broadly, what is the work of translation doing in this book? When did translation fail? And potentially, what was afforded in these failures and moments of incompatibility?

Thuy: I love that question so much and I think you’ve hit on something that is actually at the crux of what it means to think across national boundaries. What does that actually look like? And how can we do that methodologically? Theoretically? But to start with what you just mentioned, I think this book is in some ways a contribution to the work that many scholars have done on the intimate dimensions of empire. How do we think about empire through a very particular embodied lens, in this case, through skin?

You’re absolutely right to say that this requires translation, and translation is a messy process. Sometimes understanding fails. Sometimes words are too incommensurate. Part of what I was trying to do in this project was to think about how we might begin to recognize each other, really see each other beyond the surface. How do we actually begin to perceive each others’ capacities for pain, capacities for joy?

In the first part of the book, my attention is on these men of science, and how the scientific method is about an extractive move that fails to, and intentionally fails to, recognize personhood. One of the things that I talk about in the book is the ways in which, for instance, in Vietnam, the word for “body” and the word for “person” are the same. That doesn’t mean that there is no struggle for personhood or that subjectivity is not constructed. But it is different from seeing the body as an object, or a series of parts that don’t necessarily add up to a whole. In the second part of the book, I’m trying to think about how this different epistemology of the body–of skin–can lead us to different places.

One of the ways that I might be contributing to this conversation about translation is in thinking about those moments when things don’t translate. Those moments when we know and we’re not going to say. We can call it a kind of ethnographic refusal. That’s one concept we can use to think about it—but I think it might be even more than that. There are moments, for instance, when the ladies in the salon say, “Well maybe she has been exposed to the poison, but I’m not going to say that. I’m not gonna say that because that’s a horrible thing to say” or “She might already know that. I’m not going to say it, I don’t need to say it.” We both know what is going on and we’re not going to say. There’s tacit refusal. But there is also a tacit recognition. A kind of recognition that doesn’t require telling you the truth of your condition or making you confront something you don’t want to confront or announcing something you don’t want to announce.

You know, in translations, there is often an assumption that we want to have the most apt replacement for a word or the clearest metaphor so we can speak across differences. I guess what I’m trying to think about is, what do we do with those moments where there’s opacity and we’re okay with it? There’s intentional unclearness. And we’re actually okay with it because it doesn’t stop us from understanding. And it actually sometimes does help us to recognize each other better.

Claire: I really, really love that. And it’s so instructive for how scholars and others might come to know one another, be with one another, live with one another. I think that at the heart of what is so transformative about Experiments in Skin is that it gives us methods for how to live, how to do life in ongoing crises. The sort of refusal that you’re speaking about is one such kind of everyday method for living a livable life that you surface throughout the book.

Thuy: Yeah, I mean I think it’s a hard thing to say. But as scholars we have a will to know. We want to find out. We have a research question and we want to get it right. And to be able to live in that space where the will to know is not the only will, it’s not the only desire, it’s not the only way of being. To live with opacity, to live with uncertainty.

These are really, really difficult lessons for me. Lessons that I’m still trying to learn, especially after living through something like the pandemic. In some ways, it is the lesson we all need to learn. We live in radically uncertain times and we want to do everything we can to bolster ourselves against the kind of precarity and risk that’s produced by uncertainty. And sometimes we can’t. And what we have to do is figure out how to live with that. That was one of the big lessons for me and it’s not a lesson that I can easily take up because I want to know and I want to secure against uncertainty. I’m a good neoliberal subject too (laughter)! I want to manage my risks. I want the good outcome. How do you live in that space of uncertainty? Because that is the condition that we are in.

Claire: Absolutely. And I’m wondering if you see that informing what felt like a kind of collective preoccupation with beauty, skincare, and wellness during the pandemic. Because it felt like it was one of the very few things that we could shore up and secure. It was like, well, at least I can make sure my skin stays clear when everything else was kind of just on fire.

Thuy: Exactly. I mean, I do think all of this is happening at once. On the one hand, I get how people try to take care of themselves as a kind of hedge or a salve, a relief and remediation against a really, really brutal world. On the other hand, what I was trying to say in this book is that the concept of self-care needs to expand because self-care actually doesn’t work unless care for others is also a part of it. We saw that clearly during the pandemic, in the emergence of mutual aid and other practices that recognized that our fates are actually very intertwined. That one of us can’t be safe if the rest of us are not safe. The kind of vision of care that I saw in my research was very, very relational. Relational in ways that I think are so different from what the consumption of beauty means for us here [in America]. Beauty, for the women I met, is also fundamentally about a way of living, a way of constructing life, a way of being in relation with each other, a way of doing things.

Of course, beauty in Vietnam is also about meeting certain kinds of standards or asserting certain aesthetic priorities. Beauty is all those things. I don’t want to reject or make people feel bad about wanting to take care of themselves, but I want to encourage us to expand beyond this idea of beauty as individual transcendence. And of course, I’m not the only one who has said this.

Claire: I think your book is so careful and generative in attending to beauty as something that can feel really compromising and also deeply animating. And I think what I hear you saying and what I’m also reminded of is how hard it can be to talk about beauty and what it means for us in our lives.

I think often about something that bell hooks has written. She says that we need to theorize what beauty means in our lives so that we can build up critical consciousness, especially “when we lack material privilege and even basic resources for living.” And on the other hand, we have these aesthetic philosophical theorizations of beauty that are telling us that beauty offers this kind of “unselfing” experience, in the words of Iris Murdoch. It takes us out of ourselves. But, I think your book and other critical beauty studies scholars complicate this by showing us that this unselfing is always already mediated by social and political forces and institutions. And so, I’m wondering, how has beauty and its meaning changed for you the more that you’ve studied it, the more that you’ve sat with it and lived with it?

Thuy: I think it’s changed in all those ways that you just mentioned. Somebody reminded me of this really, really wonderful essay by Christina Sharpe, in which she describes beauty as a way of doing things, a way of existing, of caring. The essay is called “Beauty as Method,” and it came out after I finished writing the book. But when I read it, I saw that [Sharpe] was actually saying in beautifully succinct ways what I was struggling to say.

That’s the appeal of thinking with beauty, right? I don’t think in general that when we’re engaging with aesthetics, we’re actually seeking individual transcendence or to be outside of ourselves. I think we’re actually seeking ways of being in relation.

Claire: Yeah, there’s so much here that is blowing my mind and then also suturing it back together. This idea of beauty as being profoundly about a desire for relationality and a practice of relationality. I’m wondering if you see beauty in the potential for a kind of asociality, too. Is that possible? I’m thinking of this emergent scholarship around Asian American aesthetics, around ideas of inscrutability, opacity, and asociality. And I’m wondering, is there beauty there?

Thuy: I think asociality is a form of sociality, right? In the way that being anti-fashion is a form of fashion and fashioning. I think there are many different kinds of sociality and many different forms of relationality. Even the desire to hold yourself back, to not make yourself known is a way of being in relation. So yes, I do think so.

And these are some of the questions that are coming up as we take more seriously what beauty is and what it can open up for us. What is the role of aesthetics in our everyday lives? I’m not of the view that there is an “Asian aesthetic.” But, I do think about things like—you know, one of my first jobs was teaching in an art history department—how come there are so many landscape paintings in Chinese and Korean art history? Why is the landscape “the thing” rather than the portrait? Or the domestic interior? Or the fruit bowl? And I think to me it has something to do with that kind of relationality. A kind of contemplation of our place in the world [if there is a human figure in those landscapes, they tend to be very small]. And I don’t say that to essentialize Asian aesthetics as only concerned with thinking about our relationships. It’s many different things. I say that to encourage us to think about what material relations we can glean through the aesthetic realm. What can we learn about economic life, about military history, about scientific knowledge, about all these things that we don’t think live in the aesthetic realm? Whereas, I think everything lives in the aesthetic realm (laughter)!

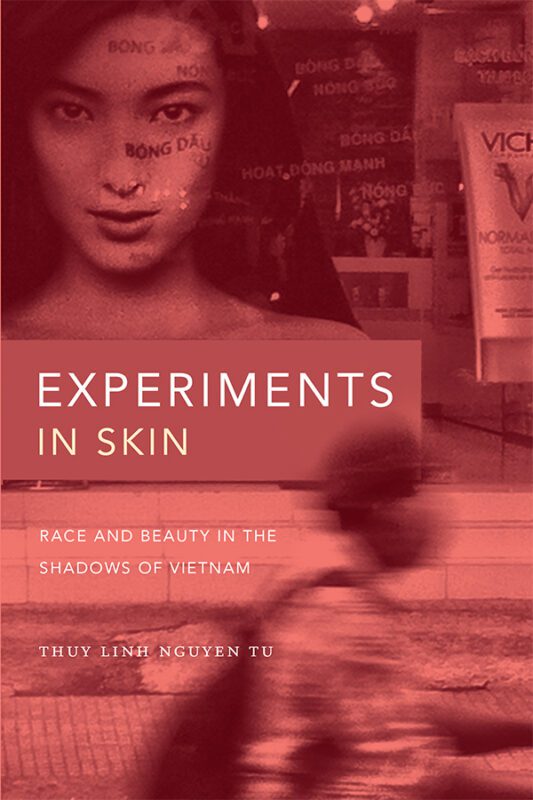

Claire: That’s super helpful. I want to keep thinking with aesthetics. I’m really just so taken by the book itself as an aesthetic form. Like, this is a beautiful book. This is a beautiful cover. And you write beautifully. I’m borrowing a question that I’ve been asked by my own dissertation advisors: what does it mean for you to write beautifully and to have produced such a beautiful book when what you’re also writing about is beauty’s very indebtedness to violence?

Thuy: I say at the end of the book, beauty is often an alibi for violence, but it can also be an entree into understanding that violence. And I want us to think about both. I want us to think about the ways it cuts and the ways it ties. I want us to think about the ways it hides, the ways it opens up. That’s why I was so interested in thinking through skin because it’s all of those things: it separates and connects, it conceals and reveals. It produces a surface and then an underneath, an above and beyond, it spatializes even as it temporalizes. Skin is a surface where we can sense both space and time. One of the ways that we see the passage of time on our bodies is on our skin, right? That’s what a wrinkle is, a mark of time. We can’t help it. And no matter what anyone wants to tell you, you can’t stop time from being recorded on your skin.

So I guess I want to think about all of those dimensions. I want us to also think about what beauty enables, as well as what it hides or demands or signals. And I so appreciate you saying that this book is written beautifully and it’s a beautiful book. Actually, the cover is a photograph I took while I was in fieldwork. So the aesthetic for me in this book is deeply, deeply everyday. It’s an image that I just happened to take as I was walking by. And there was this whole debate with my editor about the cover. Because when you publish a book, they ask you either to submit images or to give words that you want the cover to convey. I didn’t know what to say so we struggled with the cover. It was a last minute decision to use that pretty banal image. But for me it was perfect because it signaled how important it is to think about aesthetics as a practice of the everyday.

There are, of course, many acceptable and good forms of scholarly writing. Some authors lay it out pretty clearly, like “I argue this, and I draw on these fields and scholarship, and I’m explaining this phenomenon.” I think that is a super helpful way of conveying information. But I say in the book that I was trying to tell a skin story, a ghost story, and a war story. And to me, a central element of a good story is that it can move you.

I remember I was giving a talk and Viet Nguyen was in the audience. And he asked me, “You keep using the word ‘story.’ How is this a story?” And I thought “Oh no, why did I say that, like I was some real writer? In front of a real writer. (laughter)” But what I meant was that I was hoping to reach people in many different dimensions—reach them emotionally, reach them intellectually, just reach them. Like I said, there are many different ways that we, as scholars, can convey the research we do. Here, I was trying to think about how to convey my research in a way that might push beyond the argumentative mode.

Claire: Absolutely. I mean, this is why I loved the book so much. This book has traveled with me from Berkeley to Toronto to Korea to Japan. I took it with me to the DMZ. Your book travels in all of these ways precisely because the way you write is so much about attending to the textures of everyday life. And the way that you honor that is through the prose, the writing. I love that so much. It’s so instructive for scholars who are writing about things that would otherwise be taken for granted as excluded from the realm of the aesthetic and the beautiful. We’re writing about war, military, empire—

Thuy: Science, commercial culture, all of that.

Claire: Yes. I also love that you mentioned the book cover and what happened with the photograph and its selection because I’m not sure if you’re familiar with the model in your cover image. Her name is Tiana Tolstoi and she’s a French Korean model. I first came to know of her through the Korean modeling scene and I’ve been following her work for years now. And I mean, this cover is really such a rich palimpsest of everything the book is about. For instance, she’s modeling for Vichy, which is this French dermo-cosmetic brand, and she herself is mixed race French Korean. And so, I’m curious if and how this image informs the book now in its current life.

Thuy: Yeah. I mean, she was at that time everywhere. I think people are often surprised when they go to Asia and they think it’s all going to be billboards of American celebrities. And then there’s Korean actors and Chinese models. I think people are still laboring under this impression that there is an American cultural hegemony [in Asia], but this is at the very least fragmented and fragmenting. In an essay [“White Like Koreans”] that I wrote in the anthology, [Fashion and Beauty in the Time of Asia,] I talk about the influence of Korean culture in Vietnam and the kind of aesthetic ideal, which is also an economic ideal, that Korea represents in Vietnam. In that piece, I was trying to make the argument that in order to understand cultural circulation in places like Vietnam, we have to think about the region as a unit of analysis. The region really helps us to fill in that gap between the local, the national, and the transnational, and helps us to better understand the multivalent nature of transnational cultural flows.

Claire: And I think what’s so wonderful about the cover and about what it does aesthetically and conceptually is that it links your works together in that way. Because I remember when I first saw the book, I was reminded of your essay in that anthology. And I was like (gestures to book cover) “White Like Koreans”! I mean, it’s just a really synergetic, animating way of bringing your works together.

Thuy: Right. If you read the Vietnamese words [in the book’s cover image], the storefront is not advertising products that promise lightness. They’re about oiliness and dryness, how to treat these conditions that are not really about the color of your skin so much as it is about the clarity of your skin, which I think is also a very Korean thing.

Claire: If we began our conversation thinking about arrivals and how you arrived at the book, Experiments in Skin, I’m also wondering about returns and the experience and the work of returning in your book. You write in the book that while in Vietnam, it became clear to you that you needed to return to the United States to visit the archives there in order to uncover the fuller story of beauty, race, and war. And yet your ethnographic research in Vietnam itself was a kind of return wherein you travel back to the country that you were displaced from. Personally and methodologically, what was this sort of dual return like for you? And in these returns, did you experience the very things that you write about throughout the book, which are in Caren Kaplan’s words, who you cite, these “unruly intensities”? And if so, how did they come to shape and give texture to the book?

Thuy: Yes. That’s such a beautiful question and I really appreciate it because it’s such a thoughtful way of thinking about what I did, which I hadn’t even thought about in those terms. There’s a couple of things I would say. And you may have experienced this as well having done work in Korea, this experience of being the diasporic subject who returns to study “their own people.” I know Dorinne Kondo has written about this—about the ways that the ethnic subject of the US state then becomes situated as a national or even a returning diasporic subject, which then frames both your research and your sense of self in particular ways.

People in Vietnam used to say to me, “Oh, you have Vietnamese skin” And I would say, “Well, you know, I live in the US.” And they would say, “But you’re still Vietnamese.” Those moments forced me to wonder: “What is it people see when they look at me in these different contexts? And how does that shape the way that I see what’s going on?”

Another puzzle for a lot of us doing this work as “returnees” is: “Where does the field begin and end for you?” My mom is one of 10 kids and my dad is one of 13 kids. And so, I honestly have like 40 cousins in Vietnam. I always joke that I’m related to everyone. I spend a lot of time there just seeing family. That is not research. But there are things that I know that I can’t unknow just because it wasn’t in my field, or I didn’t learn it through research methods. So how do you negotiate those experiences during ethnographic work?

I say [in the book] that it was my family friend, my childhood friend who led me to my research site. I know a lot about her and her family. And, as I mentioned in the end [of the book], I’ve visited her brother, who died shortly before I left. His was the third funeral I had gone to in her family. As you know, in Asia it’s all about the connections. It’s about who introduces you into the scene. So obviously my intimate and familial relationships have opened doors for me. But it has also situated me in a kind of web of relation, of life and death, that is really hard to get out of. I’m still in touch with all these people. There’s a way in which I know the conditions I write about in the book very intimately. And yet, I am aware that there are ways in which I cannot really know them, and, moreover, I don’t want to exploit what knowledge I do have for my own scholarly work.

This affects how you reflect on your research as well. I had a student ask me during a presentation once, “These people are going to this place to take care of serious medical conditions. Isn’t it unethical to just be like, ‘Oh, drink nettle tea.’?” And I said, “Well, let’s think about the options here. Let’s think about how they ended up in this place. And let’s think about what are the alternatives to this kind of care that they’re getting.” And I’m trying to get them to think about all the different moral and intellectual frameworks in which not insisting on biomedical intervention is in fact a form of care.

But I am really, really mad that those are the options. And when I come back and I’m in the archives, I cannot believe how these men are talking about the mass killing of Southeast Asians in such a disaffected way. They don’t have any unruly intensities. They don’t have any intensity at all. And I’ve said this before, but I felt, “Oh, now I get what people mean when they talk about the violence of the archive.” Because you’re sitting there and you’re looking at how they’re talking about “could we use malaria to kill people” as a kind of a problem they’re trying to solve. A kind of scientific and military problem, as if there are no humans on the other side of that question. I say in the acknowledgements, this book was so hard to write for so many different reasons. And those are some of the ways that were hard for me.

Claire: I really appreciate that and I really thank you for sharing. I think the devastation that you’re speaking of is so much about the ways that war is no longer recognizable as such, that it is not—and you argue this so clearly and beautifully in the book—this temporally experienced event with these very clear demarcations of a beginning and an end. But actually, war gets vitalized constantly and differently throughout our lives. And that’s really hard. It’s really hard to be living amidst such persistent loss. I think what your book points to and what it helps us to see and to feel is how these unruly intensities, in your words, “errant feelings, displaced sensations, misattributed pleasures” can create these cracks, these kinds of frictions that produce these leakages. And I am really thankful for that.

Thuy: And I think they produce them in me too. This is part of what you’ve been asking me all along. I’m not outside of this scene. I’m not impervious to it. And nor are you. And that’s in part what I think is potentially useful about the work that we’re all trying to do. It is to open up these spaces where there are cracks. And to look into them and to see what we make of them and how we might exploit them, and how we might open them up further. That’s what I find really valuable about the work of students who are coming up and bringing new questions and opening up new cracks and making us look into these spaces and forcing us to think differently, to move differently. And, you know, I feel really, really gratified to be working in a place where I’m constantly in dialogue with students who are doing this. You included!

Claire: Thank you so much, Thuy. I feel so lucky to count myself as part of your genealogy of scholarship. It’s such a gift to be able to be in conversation with you right now in this capacity and also through your writing and your work. I know the same is true for other students. I’m just really grateful for the time that you’ve taken today to speak with me. And I’m so excited to see what comes next.

Liked what you just read? Consider donating today to support Southeast Asian diasporic arts!

Thuy Linh Nguyen Tu is Professor in the Department of Social and Cultural Analysis at NYU. She is the author or editor of five books, most recently, Experiments in Skin: Race and Beauty in the Shadows of Vietnam (Duke UP, 2021), which was honored with multiple awards, including the R.R. Hawkins Award, presented by the Association of American Publishers, the PROSE Award for Excellence in the Humanities, as well as a Victor Turner Prize from the American Anthropology Association.

Claire Chun is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Berkeley in the Department of Ethnic Studies with a Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies. Her research explores how modern conceptualizations of “Korean” and “Asian” beauty, wellness, and aesthetics are shaped by overlapping forces of US militarism, tourism, and humanitarianism.